For this assignment, I decided to play Doki Doki Literature Club (DDLC), which is a visual novel game created by Team Salvato in 2017, available on the DDLC website, as well as Steam, Mac, Windows, and Linux.

Spoilers below!🥹 Don’t read unless you’ve played DDLC!

—

I have seen this game’s characters in the past and always thought that it was just a very sweet dating sim centered on joining a high school literature club. However, after about two hours of playing, what starts as a lighthearted romantic visual novel very quickly turns into a psychological horror story that has wall breaks and changes the game play heavily.

[Image of the warning screen at the very beginning of the game.]

From the very beginning, there is a warning that creates some foreshadowing of some kind of horror aspects, but it’s easy to play this off thinking they mean high school drama or mental health issues. As you start the game, it feels like any other visual novel where you chat with new characters and write poems to impress the four girls in the literature club: Sayori, Yuri, Natsuki, and Monika. I picked words for poems, talked to each character, and started to notice small things that felt off as we talked to different characters. For example, music would start to cut out and the screen would go black during weird scenes, or that would be image glitches at key choices.

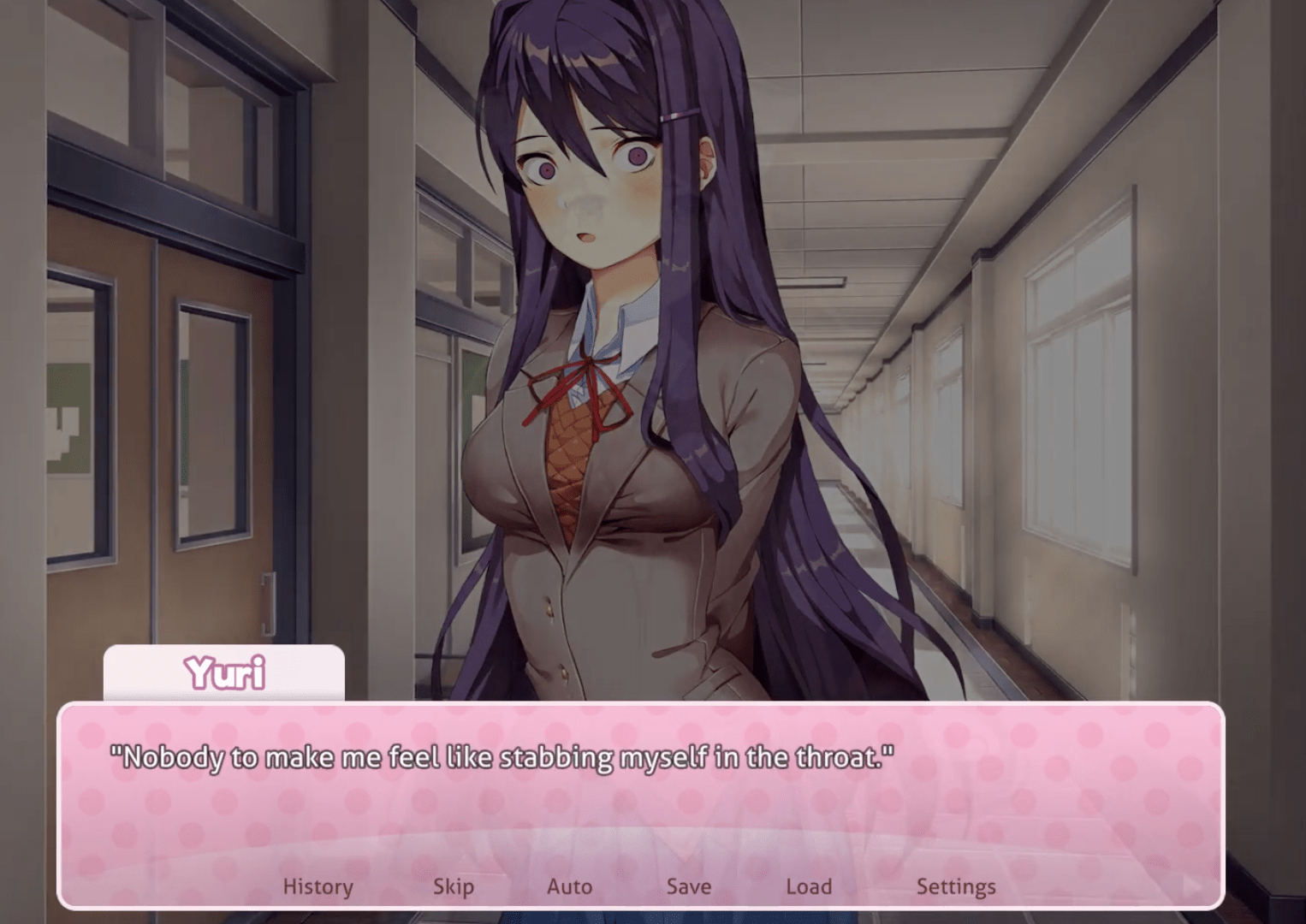

[Image of dialogue with Yuri where she seems scared and says something strangely disturbing.]

[Image of the text during Yuri’s death, which is just a lot of gibberish but is unsettling since you can’t talk to her in her last moments.]

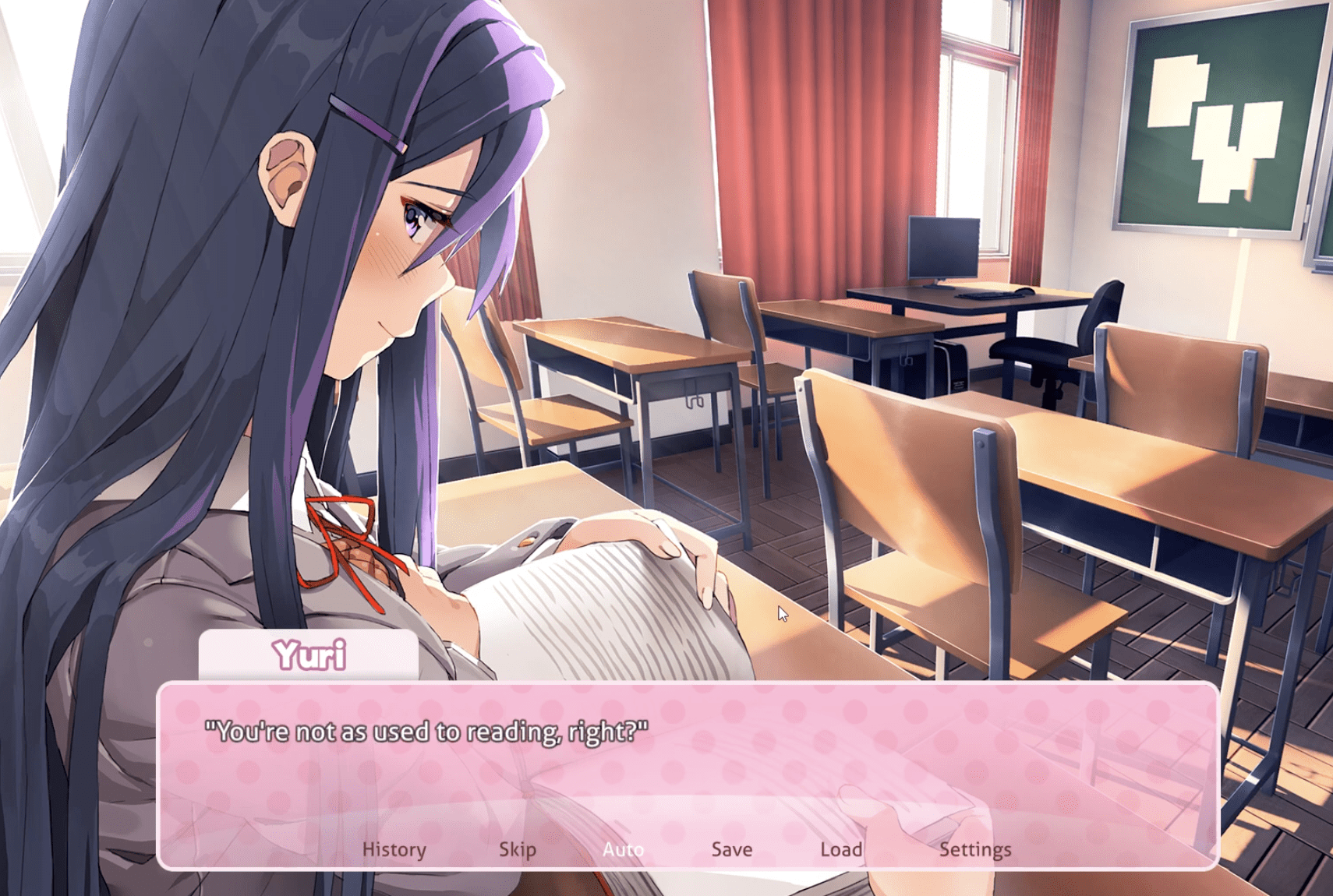

At some points the characters would also give long glances or just look very scared, which made the otherwise cheerful atmosphere and music feel unsettling. For example, at one point you’re reading along with Yuri and she’s looking directly at you for a long time, and you mention in your head that you don’t think you can keep up, but then she says not to worry about it as if she heard my thoughts.

[Image of reading along with Yuri and her glances.]

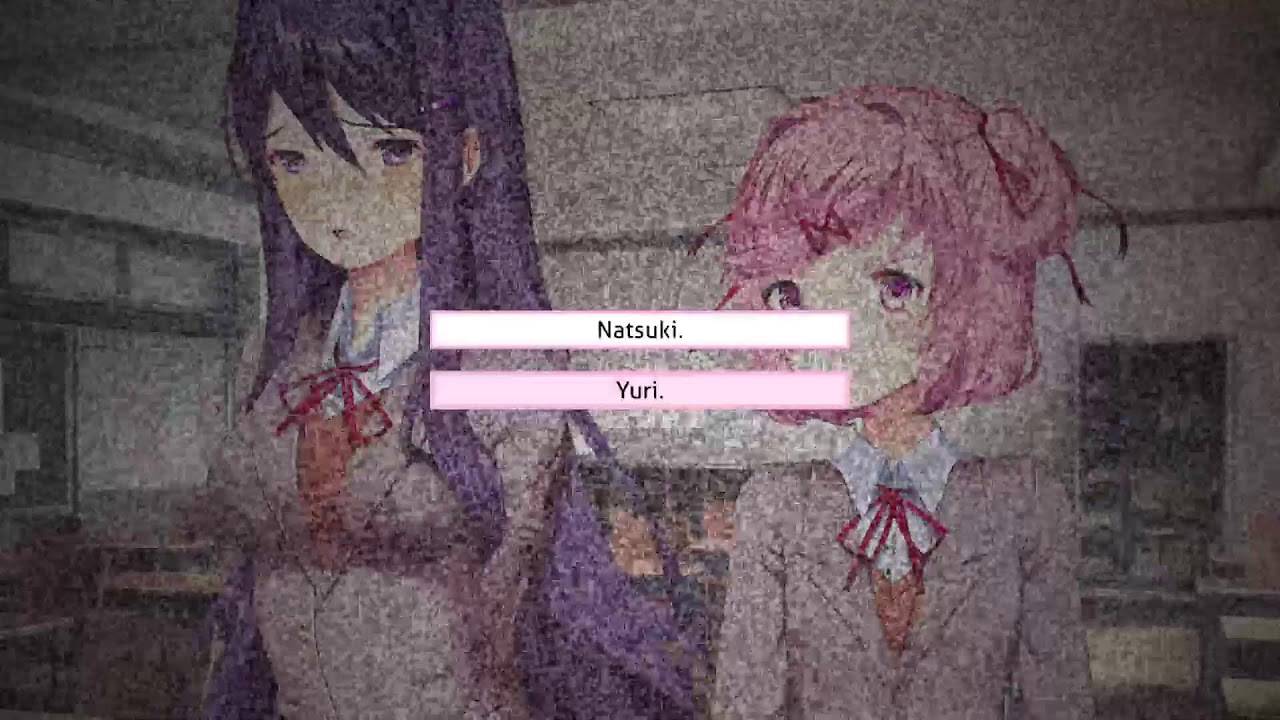

DDLC’s subgenre is mainly a visual novel, but it borrows aspects of a choose-your-own-adventure game. By slowly revealing its horror in this way, I think DDLC is doing a really interesting thing by taking advantage of the comfort of a dating sim and visual novel and flipping that idea on its head to make the chaos of the ending more jarring. Somewhere around an hour and a half into playing, the game starts to change more and you get a sense of that psychological horror that it warned you about in the beginning. You can make dialogue and poem choices that seem to affect who you get close to, but as the story progresses, it starts to become clear that no matter what you pick, things spiral out of your control.

[Image of glitched screen where everytime you click Yuri the screen zooms in and prompts you again. ]

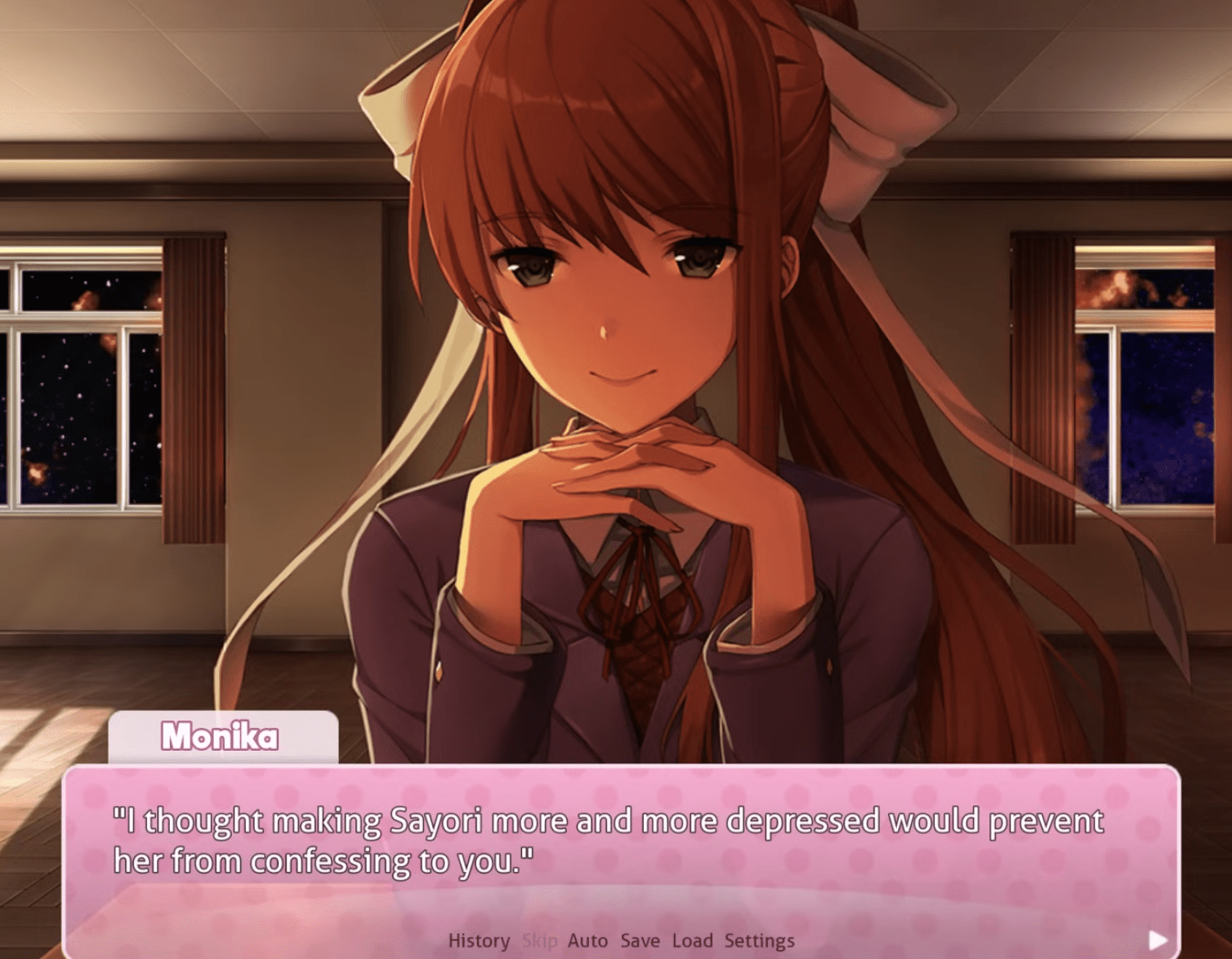

Because this game operates with user choices throughout the way with options like choice boxes and save files, it makes the twist of Monika deleting other characters’ files and directly talking to you even more shocking. In this way, it’s almost like the game uses its own format of a visual novel as a storytelling device.

Thinking about the 4 E’s:

Exploration happens both inside and outside the game as you explore relationships through your choices, but later, exploration becomes literal when you realize you can access the game’s files and delete characters. Engagement comes from routine of the daily club meetings and poem minigames that make you feel like you’re actually interacting with these girls in a real high school setting. It’s easy to fall into a rhythm of clicking through cheerful dialogue and seeing small reactions from each girl. The emotion comes in when that rhythm starts to break and there’s subtle (and then not so subtle) changes in the visuals and distorted sounds signal that something is very wrong. The game creates a lot of anxiety and feelings of tension as you interact with the girls in the late game. Moreover, as a player you start to build empathy towards a few of the girls, especially Sayori, as she talks about tackling depression with a surprising seriousness for the rest of the game. Spending time with her and then losing her in such a graphic way made me feel shock and guilt thinking about if my choices could have led to a different outcome in the story. That sense of helplessness made me reflect on how many games disguise limited agency as choice. In DDLC, even the act of saving or quitting becomes part of the horror because Monika knows when you try.

[Image of the player’s inner dialogue after Sayori’s death, making you feel guilty about not being able to help.]

[Example of a sort of fourth wall break after that prompts you as a player to try out a new storyline.]

What’s especially interesting about DDLC is how it uses the aesthetics of horror to comment on the dating sim genre. The cheerful visuals and music, paired with the disturbing events that follow, highlight how traditional dating sims often oversimplify emotions. Sayori’s depression and Yuri’s obsessive attachment expose how women in these games are often written as emotional objects for the player’s comfort. I think DDLC is unique in that it forces players to confront that dynamic by making affection dangerous instead of rewarding.

[insert image of Monika’s confrontation scene, where she keeps eerily keeps eye contact with you the whole time.]

Even so, DDLC isn’t perfect. The depiction of Sayori’s suicide is abrupt and graphic. While it’s meant to shock players into empathy, it can be distressing without warning. This choice raises questions about how far games should go in manipulating emotion. I think the same message could have been achieved through subtler means, allowing empathy to come from understanding rather than trauma. In my own story, I want to take inspiration from DDLC’s ability to break immersion for emotional effect. I love how it uses small, deliberate glitches to shift tone rather than relying on dialogue alone. I’d like to experiment with this in my own interactive fiction by finding gentle ways to make players aware of the interface without scaring them. My goal is to create more reflection than shock necessarily. I also want to build empathy gradually, letting characters reveal themselves over time instead of depending on one major twist.

Overall, Doki Doki Literature Club is a really great example of how a game can use its medium against itself. It uses the comforting structure of a dating sim to pull players into something uncomfortable and transforms a familiar genre into a critique of control and connection. It made me rethink what interactivity can mean and thinking about getting more meta since saving or deleting a file can all become part of the story.

—

Notes on Game Design as Narrative Architecture: