I very much don’t consider myself a gamer, and my relative lack of experience with games of all kinds (both board games and video games) surprised some of my fellow classmates. After all, why would I be taking a game design class if I spend so little time gaming? It’s a perfectly valid question, and my answer is that I find the idea of game design fascinating, and generally more fascinating than actually playing games.

Don’t get me wrong, there are some games I adore like Undertale or Subnautica. But in the relatively little free time I have, I generally find it more rewarding to make things than to consume other people’s things. I enjoy creative writing, making visual art, and composing music, so game design naturally appeals to me. Video games in some ways feel like the ultimate artistic medium to me because they give you the chance to create an interactive experience that combines all of those skills, plus fun technical challenges.

Before the class, I mostly thought of games in terms of their visuals and how they communicate their narratives since I like focusing on art and stories. Carefully thinking about game mechanics, especially in terms of formal MDA design language, was pretty foreign to me, so I anticipated that this class would help me with that a lot. I like making art, and I like coming up with game ideas that sound fun or have interesting stories, but if the game’s mechanics are clunky or confusing, the dynamics will be poor and the aesthetic vibes will be flattened, no matter how cool the overall idea is.

I think my main learnings are thinking about game design from this MDA perspective, plus the importance of playtesting and robust accessibility. As I have learned, an interactive experience like a game has way more opportunities for getting stuck or lost than a painting or a novel, and making the game yourself can make it almost impossible for you to properly test it (since you know exactly how it works), so having others try your game and noting their feedback is crucial to achieving your artistic goals. As for accessibility, I was very impressed with the range of strategies game designers implement to make their games playable by the most people possible. I’ve implemented alternative color palettes in web design for people with deuteranopia, but my thinking about accessibility in game design never ventured far beyond that or simply having subtitles. I learned about the importance of robust sound cues for vision-impaired folks, contrasting colors and highlights for deaf folks, reconfigurable controls (and controls with robust input tolerance) for folks with motor disabilities, and extra guidance for folks with intellectual disabilities. It’s okay to have accessibility features that only some people want, because you can make them toggleable! That’s the magic of a digital medium!

My greatest challenge in this class was learning how to make an actually playable game in Godot for the second project. I had a teensy bit of experience messing around in Godot before taking the class and had watched a couple tutorial videos, but this class forced me to properly engage with the engine and unravel its secrets. Very often I would notice an awesome preset feature only after implementing my own crummy workaround (such as realizing I could make a collision platform one-way to allow players to jump up through it by ticking a checkbox). Turning my ideas, like having the player jump on buttons of a remote control to move a toy firetruck back and forth, into a reality forced me to learn how the engine actually works. AI tools were helpful for figuring out the engine’s scripting language, but at the end of the day I had no choice but to learn Godot’s node structure and slowly become somewhat competent at building out levels.

Fig 1: Look Mom, I made an actual video game level! It even has puzzles n stuff!

After taking this class, I feel that I’ve grown from some dude that thinks game design is cool into a bona fide larval game designer. I had designed a game before and, after two class projects, I have two under my belt. I’ve learned to accept criticism for my ideas (which can be hard if you think something is really cool and nobody else is interested), because there’s no other way to move forward!

The coolest part of this class was making something that actually made people have fun. It’s really rewarding to watch a playtester smile and transition from testing your game into actually playing your game. That hard-to-pin-down transformation from probing exploration into genuine play is rad to watch and it feels incredible.

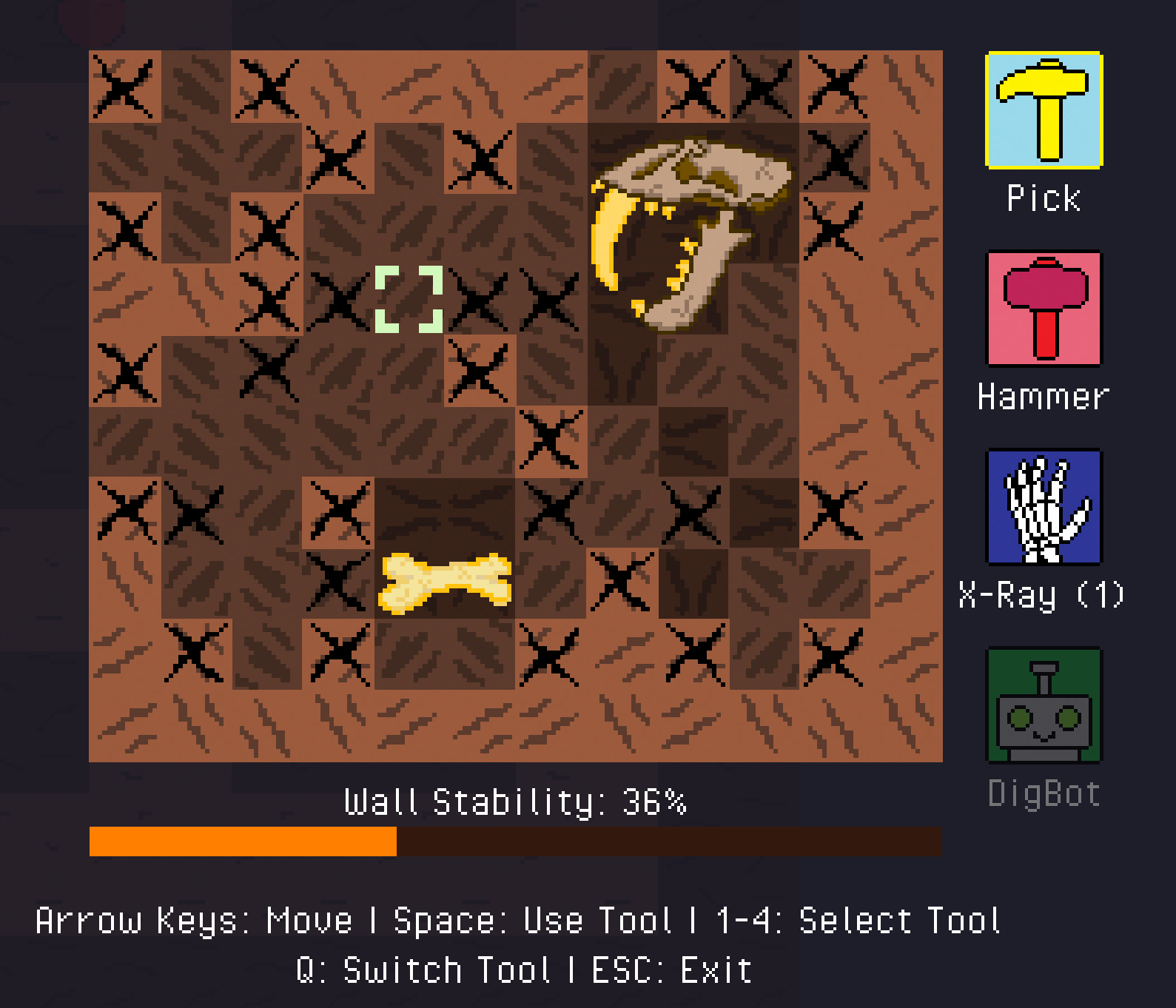

I’ll be continuing my game design journey on my own time this summer, and this time I actually sort of know how to use Godot already. I’ll be carrying all the knowledge I’ve gained in this class forward to help me design something that is actually fun to play, not just fun to think about. I’ve already started on my fossil-hunting and resurrecting game called Paleo Pals, and now I think I can actually make it fun!

Fig 2: Super early build of Paleo Pals! Coming eventually to Itch.io!

Thanks for a great quarter, y’all!

That is the magic moment– when suddenly people start having fun playing YOUR game! And I’m the same… games are an intellectual problem, and figuring out how to solve for fun is fascinating. I hope critical play made you enjoy play more as well!