For this week’s critical play, I chose to play Hades. This game was created by Supergiant games and is available on Windows, Mac, PlayStation, Switch, Xbox, and iOS. The game is rated T for Teen by ESRB and can be enjoyed by both casual and competitive players who like narrative and rogue lite games. I played on my Mac.

Hades causes the player to become invested in its world through its rich (evocative and enacting) narrative, level design, and masterfully designed game mechanics that seem effortlessly tied to its story rather than tacked-on.

Hades bases its story on Greek mythology and therefore has an immediate cultural association that draws the player in, especially if they are familiar with classics and the Western canon. Nearly the entire cast of Hades—the gods, demigods, enemies, and humans—are real figures in Greek folklore or are heavily inspired by them. In addition, all the game locations—which include the Underworld and its constituent regions (The House of Hades, Tartarus, Asphodel, Elysium, and the Temple of Styx) as well as the surface world—also come directly from the same legends. These characters and locations are beautifully designed from both a visual and audio standpoint, striking a balance of being faithful to their canonical depictions while staying unique to Supergiant’s particular vision.

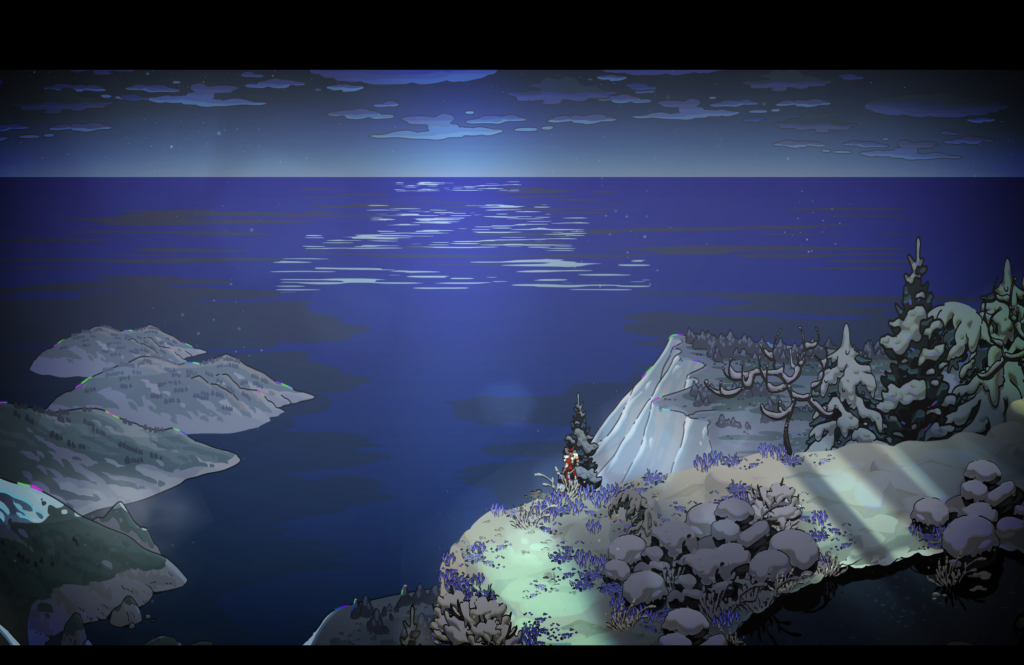

Figures 1-4: Asphodel (Eurydice’s Room), Elysium (Patroclus’s Room), The Surface (Dusk), The Surface (Dawn). These are snippets of some of the beautiful location art in Hades.

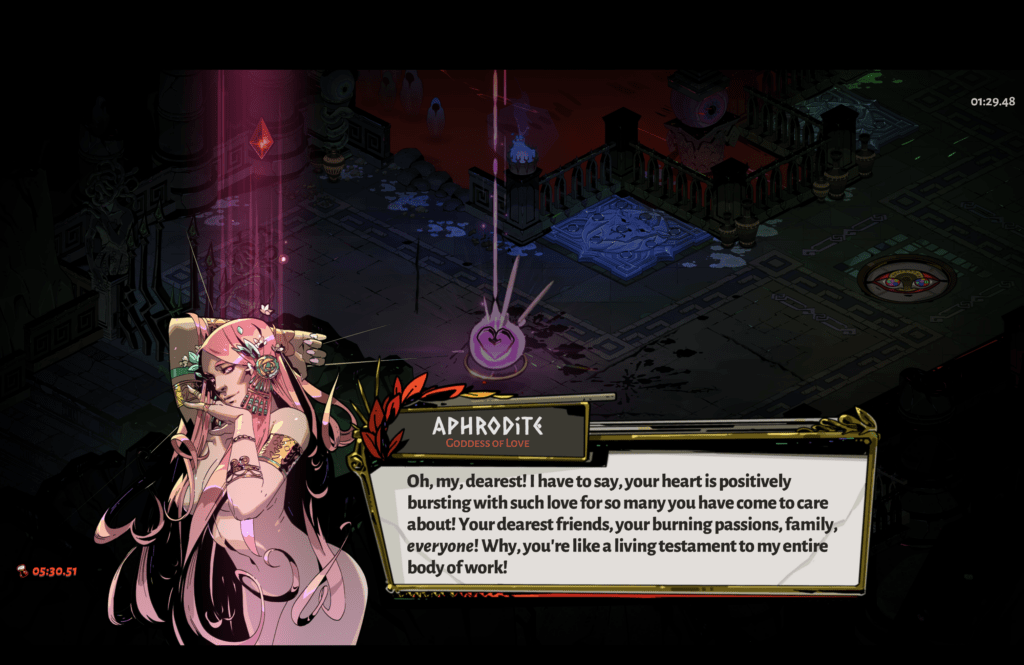

Along with Hades’s evocative narrative from its locations and characters, the game also relies on enacting narrative. The player controls Zagreus, a literal god who is the son of Hades and Persephone. The main objective of the game is to escape the Underworld by fighting your way out of it. Along the way, you meet your extended family, who are also literal gods and grant you their power in the form of boons (combat power-ups). They don’t merely serve as the conduit for the player to get upgrades and feel blessed with divine power; they are characters with their own unique personalities that draw from the Greek gods’ canonical characterization, which enhances the player’s connection to them and the overall narrative they serve.

Figures 5-8: Character dialogue interacts with Aphrodite, Dionysus, Hermes, and Zeus, each demonstrating their distinct character art (that correspond to the types of powers that the player receives) and personalities.

Like other roguelites, one of the core mechanics is that a player’s run ends when they die, forcing them to start a new run from the first location. This is a straightforward game loop, but it actually serves as the primary form of narrative progression: whether you win or lose a run, you eventually have to die and return home (The House of Hades), where you are usually greeted with new dialogue, objectives, and opportunities to upgrade your character. Zagreus always loses the specific powers from the boons given to him by the gods he encountered on a particular run, but he gets permanently stronger with each subsequent run when they obtain darkness, the in-game currency that allows the player to get global upgrades in health, speed, etc.

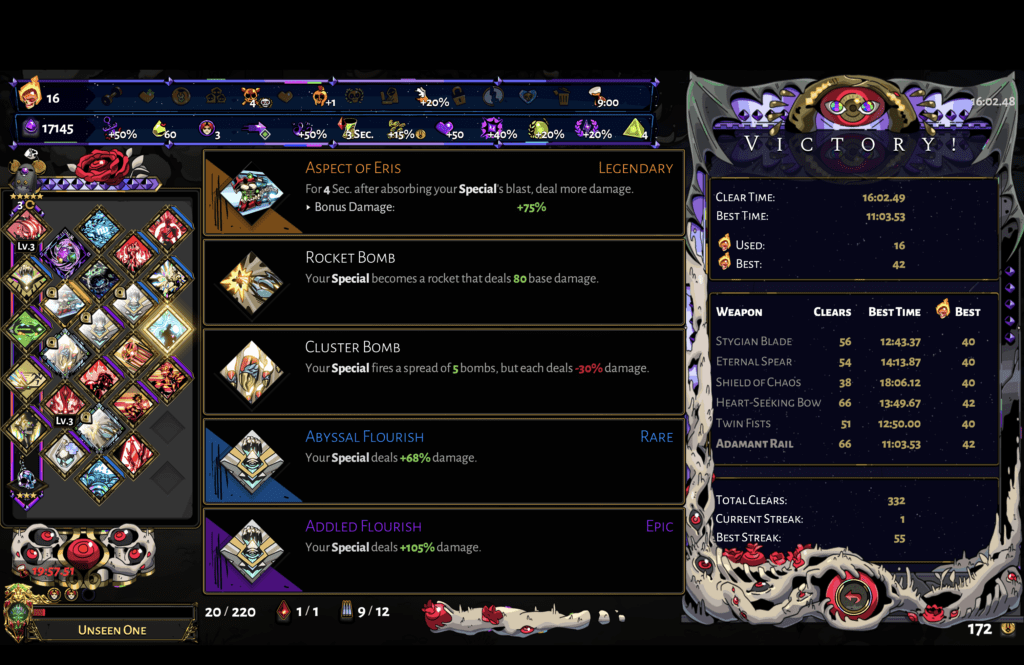

Figures 9-10: Two different builds I used to win two separate runs; the chance of encountering these particular power-ups are randomized.

Each run’s environmental levels and potential gods encountered (and by extension, powers received) are randomized, leaving the player excited to see who they will encounter on their next run, and what part of the story is waiting for them when they return home. Even if the player loses their run, they are still rewarded with narrative progression. This establishes a dynamic where the player looks forward to each run and what new stories, locations, powers, and characters they will encounter next, feeling challenged rather than completely frustrated. This sets Hades apart from other games that are harsher and punish the player by blocking their game progression while not helping them be successful in future runs or fights.

In conclusion, Hades’s narrative and formal elements combine to create what is likely one of the most well-executed roguelites in modern gaming history, if not at least the best Greek-myth based game in recent memory. The primary forms of aesthetic fun are: sensation (gorgeous game locations, character designs, and music), fantasy (diving into the world of Greek mythology and roleplaying as a god), narrative (Zagreus’s journey to save his family), challenge (getting through a run, especially with Pacts of Punishment, which are certain debuffs to the player), and discovery (untangling new plot points, reaching new locations and levels, defeating Hades and reaching Zagreus’s mother’s hideaway).

I decided to create my own ethics question this week.

One of the central themes in Hades is family, focusing on the relationship between Zagreus and his mother (Persephone), father (Hades), and extended family (the other Greek gods). The game starts with Zagreus having a difficult relationship with his father and being estranged from the rest of his family, ending with all parties reconciling. However, familial reconciliation is often not as simple in the real world. What are the shortcomings of Hades’s depiction of familial dynamics, and how could the storytellers and designers address them better?

For all the good things about Hades, it is my view that one of its biggest thematic flaws is the way in which the family dynamics are handled and resolved, largely because it does not highlight the full extent of the abuse that Zagreus endured, and glosses over the often long, difficult, and sometimes impossible process it takes to repair broken families.

Zagreus takes the proactive role in reaching out to his father, who starts off as authoritarian, foul-tempered, and physically and emotionally abusive, but slowly redeems himself by the end of the game. I take issue with the fact that Zagreus had to be the one to initiate the repair process, but that is also usually how it goes in real-life if the child wants to reconcile rather than cut off their parent. Over the course of the game, Hades gradually realizes the error of his ways, apologizes to Zagreus, and does not beg or demand for forgiveness, but rather tries to make things up to him via his actions—which is about as good as a child can get from a parent who has wronged them, especially in the real world.

However, this outcome is not always realistic or feasible, many real-world parents are often not as (relatively) open to change as Hades is and can be much more narcissistic and crueler to their children. Zagreus’s ability to be endlessly revived should not be reason to downplay the harm that Hades imposed upon him. This is not to mention the estrangement he experiences from the rest of family, which is due in part to Hades and Persephone’s choices as parents. The postgame rushes through the reconciliation between Zagreus’s immediate family and the rest of the Olympians with a brief cutscene of their reconciliation dinner, which doesn’t fully address the very real tensions that would arise in a real-world situation—for example, Demeter, Persephone’s mother, thought she was dead for years, and seemingly just accepts that she’s alive without being particularly angry at Hades or Zagreus.

Figure 11: Demeter’s response after she learns her daughter, who was missing for Zagreus’s entire life, was alive and with them the entire time! Wow! This is all we get!!! There’s no more!!!!! The goddess who was angry enough to create a permanent winter on The Surface near Zagreus’s home (and still hasn’t lifted it) just accepts what happened without protest!!!!!!!!!!

This is not to mention the fact that Zagreus is permanently tied to the Underworld and thus cannot escape Hades’s domain, so he is essentially coerced into his role as a mediator and has no choice but to live with his father and try to reconcile. He also has to cover for his parents’ mistakes by preventing a war between his immediate family and the rest of the gods, all while taking in the secrets of his family that were hidden from him for years. There is a lot to unpack in Zagreus’s family (e.g. unresolved trauma) so I found it disconcerting when all these problems were practically just waved away or resolved in a few dialogue interactions—there is way more that Hades, Persephone, and the others have to answer and apologize for than what the game addresses.

I realize that much of the family dynamics in Hades are due to the scope of the game and the fact that Greek gods are filled with messy family dynamics in canon, and are thus abstracted away; however, if I were the creator of the game, I would focus more explicitly on how the family gets put back together in the postgame and make the redemption more realistic, gradual, grounded, and earned rather than rushed and reliant on “love conquers all” tropes.

Addendum

This has nothing to do with the critical play, but I had to show off how hard I played Hades a few years ago. Behold, my 500.2 hours played and 100% achievements.