Wizard 101 is a massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) created by KingsIsle Entertainment in 2008. In this game, available via Microsoft Windows, Mac OS, Chromebook, and consoles like PlayStation and Xbox, players take on the identity of a young student wizard tasked with saving Spiral, the wizard world, from collapse. This game is meant for players aged 10 and up, although a quick scan of chat forums online reveals that W101’s user base today is largely aged 18-30—that is, the people who grew up with it are the ones who appear to be playing it today.

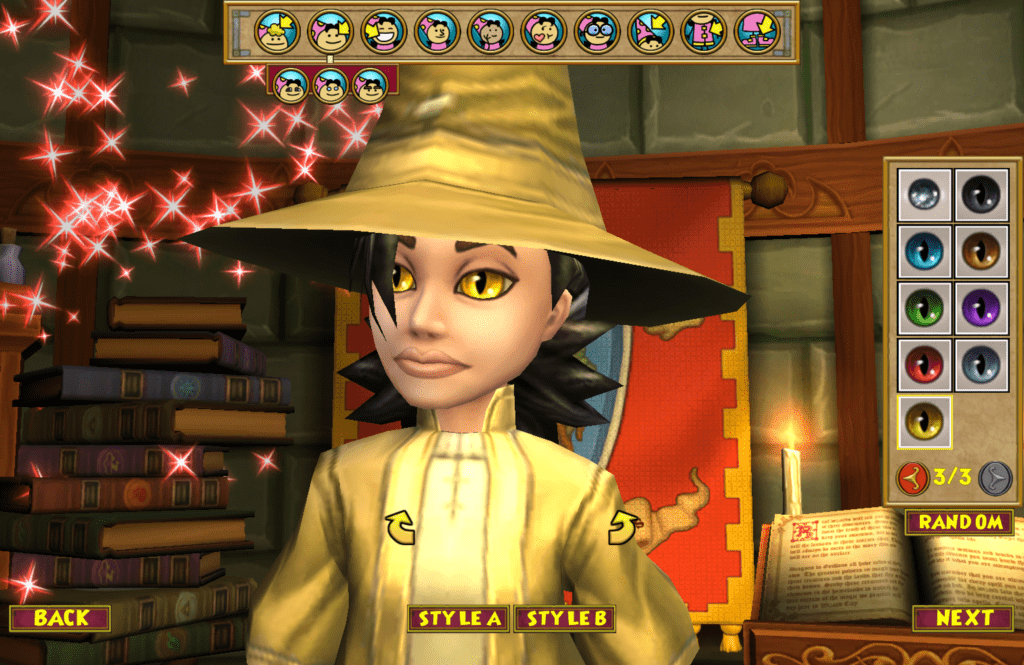

In “The Psychology of World Building,” Gabriela Pereira aptly notes that world building “has less to do with your story’s environment and more to do with the characters you put in it.” Wizard 101 follows through on this principle from the very start: at the inception of the game, the player’s first major task is to customize their avatar. They take a personality quiz-style game to determine what type of wizard they are, and then are given the option to customize various facial features (eyes, nose, mouth) and cosmetic features (facial markings, hair, clothing), before finally choosing a name for themselves.

Worth noting here is that the customizations seem to allow for two different approaches: players can make avatars that look like themselves by choosing from realistic offerings (skin tones, eye colors, and hair colors all include “natural” options), or, alternatively, they can make avatars that represent a certain fantasy (a 13-year-old can make customizations that their age would normally preclude, e.g. adding facial “paint” resembling tattoos or coloring their hair a bright pink; an adult can make customizations that are simply impossible due to human anatomy, e.g. choosing an iris that resembles that of a snake or a dragon, with a narrow, vertical-slitted pupil down the middle). In the case of the former (realistic avatars), the options are limited: there is no size representation due to an inability to change the player’s naturally slim body shape; the skin tone options start to wane as they get darker, with greater variety for lighter tones; the same can be said of hair textures, with far less representation for kinky or curly hair; players cannot choose what they wear, only the color of their clothing; there is no visible representation of disability of any kind. In other words, even the realistic options are not all that realistic. On the other hand, I found it strange that there were very few fantasy modifications—the pupil shape was one of the most notable, but this animalistic customization was not accompanied by all the other kinds of chimera options one would normally expect (e.g. tails, whiskers, ears, as seen in Picrew makers). The introduction of just one or two animalistic features felt indecisive, as if the game creators hadn’t yet agreed whether to cross the boundary of human-animal crossover. My personal redesign would likely close off the animal-fantasy options due to the abundance of fantastical creatures that players get to interact with throughout the game (i.e. if we included snake eyes as an avatar option, then what about lizard tails? Dragon wings? Fairy wings? But fairies, for example, are creatures that already exist as supporting characters or NPCs in the game—drawing a clear line between human-wizard and all other fantastical creatures would reduce confusion about a player’s relationship with these supporting characters). On the other hand, I would expand the “realistic” options significantly, offering greater representation for (plus-sized) body types, darker skin tones, skin conditions, moles, hair types, hairstyles, tattoos, tattoo placement (not just the face), disability tools (e.g. eye patch, cane, prosthetics), and clothing options (e.g. more modest, more revealing).

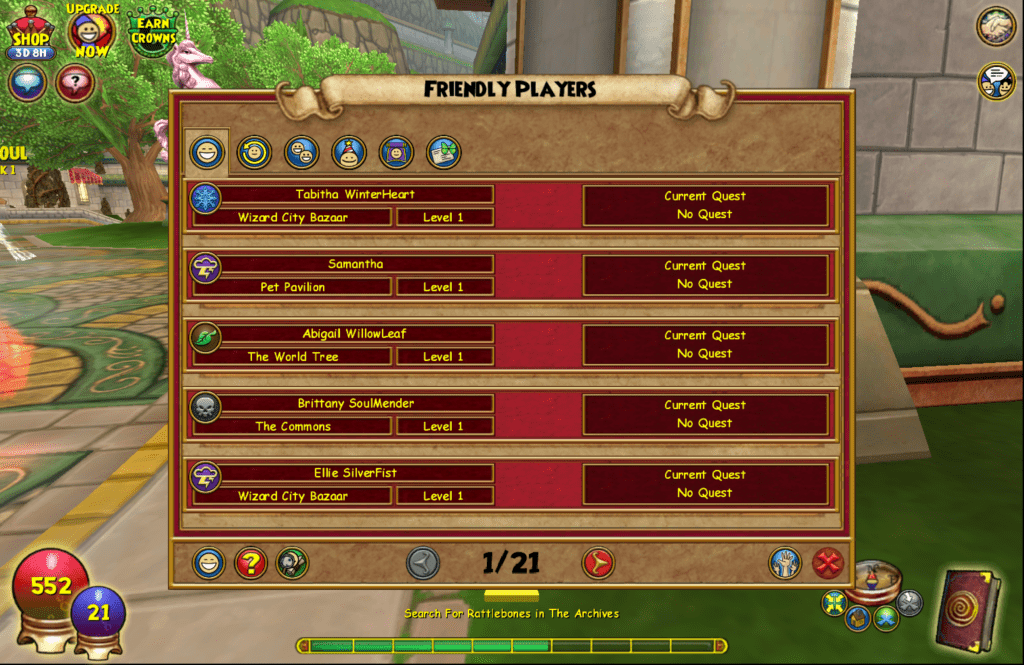

Despite my qualms about the character design in W101, I nevertheless feel that its worldbuilding is particularly strong because of its character development: it proceeds from avatar/protagonist development to supporting cast development, introducing obvious mentors (e.g. Merle Ambrose, headmaster of Ravenwood school) and foes (e.g. Malistaire), to smaller supporting cast development, introducing allies (e.g. Private Connelly, Olivia Dawnwillow, other characters that assign quests and offer guidance) and opponents in battle (e.g. Lost Souls, Skeletal Pirates). In any case, there is a clear hierarchy of importance when it comes to these characters, often organized by narrative elements like quests. Smaller quests correspond to smaller foes and smaller supporting characters, and are nested within the larger quest, which is introduced at the beginning of the arc. For example, the smaller quest of helping Lady Oriel’s fairies is just one part of the player’s exploration of Wizard City, which in turn is just the first part of the greater mission to defeat Malistaire. These frame narratives, which are common devices in literature, make for a strong sense of player investment in the plot. Moreover, W101 makes effective, albeit simplistic or predictable, passes at nuance—Malistaire is not just a two-dimensional villain causing destruction for the sake of destruction, but instead a man driven mad by the death of his wife, Sylvia, whose actions result from his desperate attempt to resurrect her. Humanizing the villain teaches fundamental lessons of empathy, a sign of meaningful storytelling. And along the way in this first arc, the player is guided through the learning curve of gameplay one step at a time: one quest introduces mana and health points as themost important player stats; another introduces the map feature, another the backpack and its various offerings: rings, mounts, robes.

Beyond the character development, W101 creates an immersive environment via its surroundings, society, and landscape. It is particularly strong in its brand identity: the fantastical, often jewel-toned colors of the clothing worn by players, contrasted by the vaguely medieval, dark architecture style with elaborate stone adornments, arches, and towers, creates a classically “wizard” like environment: whimsical, ancient, intense. Enhancing this sense of space is the requirement that players literally traverse the landscape using the arrow buttons on their keyboard, following their avatar via a third-person limited perspective (the player can see their avatar, who is always the focus or center of their perspective) or a first-person perspective (sometimes, the avatar disappears, as if the player is literally seeing through their avatar’s eyes). Finally, the introductionof other, real-life players in the same landscape creates a sense of “reality”: players can team up to defeat foes together; if one player reaches a treasure box before another, only the first player will reap the gold inside; players can make “friends” and players above the age of 13 can chat with one another. Although there exists a plethora of ethics and safety concerns with this communal aspect of the game—particularly when it comes to younger players—this is also why games with a fellowship aesthetic are so powerful: the knowledge that the game world is literally populated by other people allows players to attach their feelings of triumph and frustration to real people, establishing inter-game relationships and creating a sense of investment that is difficult to find in non-multiplayer games.