Monument Valley (hereafter MV) is a puzzle game created by Ustwo Games for iOS, Android, and Windows platforms. It asks players to guide the protagonist, Princess Ida, through dreamy physical landscapes set in an isometric view. Players must manipulate the space—the passages, staircases, and various other devices embedded in each puzzlescape—in order to get Ida from the start of each level to its end. These levels, set up as chapters each defined by a plot point (e.g. “Chapter III: Hidden Temple, In Which Ida Has an Unexpected Meeting,” “Chapter IV: Water Palace, In Which Ida Discovers New Ways to Walk”), often consist of multiple sub-levels, or individual buildings that are revealed to be connected as Ida passes through. Although MV is marked as appropriate for players 4+ on the App Store, it appears to be more appropriate for middle grade (10+) players given its sparse but mysterious narrative, contemplative themes, and lack of directive for players to follow.

MV’s magic lies in the way it treats space and perspective as plastic. Not unlike the mindbending illusions of M. C. Escher, Monument Valley asks its players to reconsider the rules we’ve livedby our entire lives by not only manipulating Ida’s movements, but by also literally altering the landscape of the puzzle.

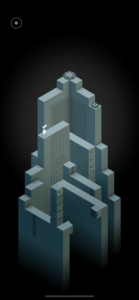

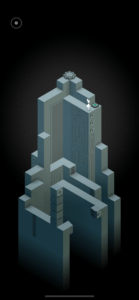

Because recalibrating one’s spatial awareness is a task that can easily become frustrating—read: difficult to the point of unachievable, and therefore not “fun”—MV approaches this task in incremental steps. In Chapter 2, it introduces levers the player can spin to rotate portions of the landscape. The spinning portions are demarcated by a slightly darker shading, asking players to pick up on clues within subtle art differences. It also introduces buttons Ida can step on to cause shifts in the landscape, as well as stairs and ladders she can climb. In Chapter 3, MV introduces doorways that will transport her from one cornerof the landscape to another, as well as vertical and horizontal sliders Ida can stand on to be whisked from one part of the landscape to another. These sliders can complicate the puzzle by creating red herrings: in the example below, because the vertical slider Ida stands on can be raised to multiple levels, the player can be led to believe that Ida should take the left slider to the ledge on the left half of the puzzle. However, in reality, she is supposed to remain on the left slider, get off at a slightly lower level, traverse to the adjacent right slider, and rise up to a higher level to access the following button. This kind of misdirection fits the ethos of the puzzle as a challenge to what players think they know—in other words, it evades the common puzzle pitfall of prompting players to blindly click and brute-force their way to a solution. Instead, it asks: are slidersmerely means of transport to stationary ledges, or can they serve as ledges to other sliders, and worthwhile destinations in and of themselves?

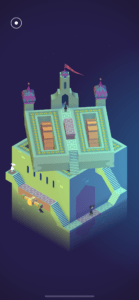

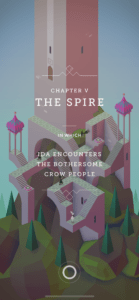

Chapters 4 and 5continue to introduce these perspective-reframing devices: Chapter 5, for example, introduces an element of time to the game via the Crow People, moving figures that prevent Ida from passing when they cross paths. Players must consider when to cross a path, whento sidestep the path of the Crow People, or when to evade them by altering the landscape (e.g. spinning the entire building, spinning the path, introducing a staircase).

Beyond the physical mechanisms of each puzzle, MV creates an introspective, surrealist atmosphere with its art direction and narrative. Each landscape is defined by clean, sharp lines and ample empty space between the isometric building and the borders of the screen. Each chapter is locationally distinct (e.g. The Water Palace, The Spire), as reflected in the shifting color palates and surrounding elements (e.g. foliage, background color).

In between chapters, Ida encounters a mysterious figure whose monologue reveals more and more about the storyline of the otherwise largely wordless game: “Long have these bones waited in darkness,” the figure says. “How far have you wandered, silent princess? Why are you here?” This vague narrative fits the minimalism of the game—it leaves room for the player to slip into Ida’s shoes as much as possible, which is crucial for a game in which the player-protagonist must physically walk through landscapes to advance. However, I wonder whether a more specific narrative, tailored to the specificity of each location, would be moreengaging. We often assume all elements of a game should follow the same aesthetic—visually and narratively. But we underestimate the power of a compelling story, even within a more minimalist physical space. For example, allowing Ida to encounter a water nymph in the Water Palace or introducing her to an entrapment narrative in the tall towers of The Spire might make the broad themes of “forgiveness” less confusing for the player by allowing them to follow concrete plot points. Instead of asking, “forgiveness for what?” and bearing the onus of projecting the notion “forgiveness” into their lives, the player might instead be better able to connect with the mission of, say, rescuing Ida from the Spire, and in the process understand, empathetically, why she is seeking forgiveness.

All in all, however, I believe that MV does critically engage the ethics of lateral thinking. Instead of asking Ida to change in order to move through the landscapes, it asks the landscapes to change for her. In other words, MV is a disability ethics game that challenges the hegemonic notions of physically disabled individuals as flawed, instead reinforcing the idea that their environments simply haven’t been made to accommodate them. This underlying belief is crucial in a game in which the protagonist must use stairs and ladders, structures typically hostile to disabled individuals. Of course, I wonder how this game could function differently if these structures were further converted to accessible pathways—ramps, for example, instead of staircases, could introduce interesting challenges of gravity and balance. Moreover, this is a game that fundamentally assumes a level of visual acuity and dexterity, which could be improved greatly by a zoom feature, for example. However, I believe that generally, MV represents a case in which literal representation is actually eclipsed by the ethos and principles of the game, however implicit both may be.