Babbdi, available on Steam for Windows, Mac, and Linux (and Itch.io for Windows only), can be considered a walking simulator due to its focus on peacefully exploring the game environment without any violence or explicit puzzle mechanics. Calling Babbdi a walking sim might be a bit misleading though, as the game allows for extreme freedom of movement, with sprinting, platforming, riding a motorbike, blasting into the air with a leafblower, etc. While Babbdi’s game environment is thematically oppressive, a brutalist concrete jungle evoking a dystopian military district, its movement options reveal a subtler narrative through embedded and emergent storytelling

Fig 1: I’ve never been so excited to “plame” a game!

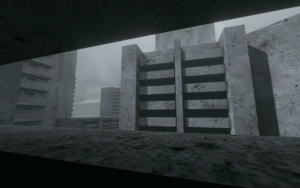

Fig 2: Yikes, off to a very brutalist start here.

From the game’s title screen, it’s clear that this game by the Lemaitre Bros. isn’t for everyone. Bizarre, garbled words and intentionally unappealing graphic design may serve to filter out anyone in the potential audience not looking for an avant-garde experience and might spook someone looking for a friendlier experience. If the user proceeds to “plame” the game, they appear in the hallway of a concrete residence tower resembling a parking structure or prison, overlooking a city of similar buildings, concrete barriers, and barbed wire with a vast wall encompassing the city in the distance. The nearest NPC, who like any other character in a residence lives without a door and only has a bare mattress to sleep on in their concrete room, offers us a baseball bat to “strike surfaces” and says he hopes to “maybe” see us again. Had I not known this game was listed as a walking sim, I would have assumed this bat was a weapon and I would shortly be dispatching monsters or guards to escape this prison-city. But while the impulse to escape is confirmed, there is never anyone to attack or defend against. The bat is a quirky movement option, allowing us to bounce off of surfaces in the game to move around, in addition to the always-available walking, sprinting, and crouching.

Fig 3: The bat man’s room. Nice place you got here.

The designers’ use of light and space instill a foreboding atmosphere as we wander through dark, dead-end passages in the starting building. Many other such passages litter the game world, and only after I moved through several of them without disturbance did I finally accept that nothing was out to get me, regardless of first impressions. And after exiting the concrete tower, we can emerge into a fairly open green space. With concrete ruins and what looks like a small flooded graveyard, I’d hesitate to call it a park, but it has a peaceful barking “dog” and is littered with soccer balls, so it nonetheless evokes a park and relieves the building tension of claustrophobia and darkness. As we struggle to find anyone to talk to in this area (just a woman floating in the flooded graveyard without words) and look onward into the twisted, but platformable, jungle of the city around us, the aesthetics of the game are inverted. A horror game sense of being stalked and enclosed becomes a walking sim sense of freedom and loneliness.

Fig 4: A park-like space with some dim sunlight and a peaceful creature resembling a dog

Fig 5: I thought this woman was dead at first, but she just floats there serenely, making a humming sound as the ellipsis showing a lack of dialog displays.

We can hop on platforms, fall hundreds of feet, ride motorbikes through canals and underground train stations, use leaf blowers to blast upward, and probably find other ways to move that I didn’t notice during my playthrough. These movement mechanics result in a dynamic of fast-moving, free exploration that heavily contrasts with the aesthetic impression of the prison-like map. Only after exploring for quite a while can we be sure that there are indeed only around a dozen NPCs across the entire citadel, none of whom are held in detention. Since we are allowed to go anywhere with any manner of movement, an implied story of imprisonment becomes one of abandonment. This oppressive place may have once been a prison, or perhaps a fortress as it’s never clarified whether the fortifications kept people in or out, but the original purpose is now long gone. We eventually meet a young woman complaining of boredom beside an empty chapel, an old woman skimming cooking oil from a sewer, and a husband sitting beside his gravely ill wife with nobody to help them. From freely bounding around and interacting with these characters, we learn that nothing is coming to help or hurt us. And with an inability to interact with these characters beyond hearing the same few, brief lines over and over, it is clear there is nothing here for us beyond a somewhat depressing playground. This is a forgotten place, not exclusively desperate, but certainly not constructed or provisioned for human flourishing. We’d best leave if we can.

Fig 5: Is this how people survive in Babbdi?

The man with the sick (and mute) wife says she has a train ticket to leave Babbdi, which will presumably allow her to receive medical attention. Around half of the other NPCs variously mention the citadel’s train station, leaving via train, and where to acquire a ticket. While we can clearly stay and explore to our heart’s content, meeting person after person that discusses leaving, all of whom appear unable to leave themselves, reinforce the implied narrative that our character doesn’t want to be here.

The designers locate the ticket counter far away from the train station and near the opposite end of the map from the starting location. This design, along with numerous garbled signs indicating a “taan stration” encourage the player to visit the train station first, where they see that the trains are running through the station, but without stopping. Colliding with a train apparently kills the player, but they simply reappear back on the platform afterward with no suggestion of gore. It’s interesting that the only act of violence in this game is a voluntary one by the player, and comes from an interaction not with a character, but a machine that ignores their presence (it notably does not slow down to avoid hitting you). Since nothing else in the game to this point can harm you, including falling hundreds of feet off a high platform, the designers subtly encourage the player to try their luck and see what happens if they stand in front of the train. I feel that the result is a major part of the game’s subtle narrative: it confirms that this place is truly forgotten. The outside world hasn’t even properly discarded it, as a train line continues operating through it, but the entity controlling it cannot see the people here, or else don’t care about them in the slightest.

Fig 6: zooming along to the “taan stration”.

Being turned away at the ticket counter (tickets apparently are no longer issued to anyone), backtracking to the starting building to accept a ticket from the man whose sick wife has now died, and anticlimactically entering a train to leave the citadel reinforce the narrative, but don’t substantially add to it. Walking, jumping, biking, and leaf blowing our way through this dismal playground to meet its forgotten residents and get run over by its apathetic trains have already told us everything there is to know about the city of Babbdi.

Fig 7: Leaving Babbdi simply has you board an empty train. You aren’t greeted by anyone or congratulated for getting on it. You just leave (as explicitly confirmed by the joyless end screen.

Ethics

In section, my group played a tabletop RPG that theoretically permitted violence (we were bears trying to pull off a heist of honey from a honey bank), none of us engaged in violent behavior, favoring stealth and subterfuge. Babbdi features no violence as far as I can tell (although it might be possible to strike NPCs with the baseball bat item, I never attempted this due to my lack of desire for violence). Babbdi does, however, encourage the player to invade the homes of the NPCs. Part of the game’s dystopian atmosphere and open, traversable world is the fact that none of the NPC’s residences have doors, instead featuring concrete entryways that open directly into hallways or the outside.

Since this game’s movement mechanics promote extreme freedom of navigation, are we free to barrel our way into these private spaces. The NPCs offer no resistance, but does that make it acceptable? The lack of doors and personal possessions may imply that these residences are not homes, just places the characters are temporarily inhabiting, but there is something uncomfortable about running into a featureless concrete chamber with a disinterested, sick-looking character and a bare sleeping mat. The mat creates the impression of a home, even if only temporary, being made out of this inhuman space. Are we really exploring, then, if people are already living here?