For this critical play, I played Dear Esther. Not having played a walking sim before or at least not having heard it described formally, I wasn’t really sure what to expect. From my experience playing more conflict and competition-based games, I fell a bit into the trap of thinking less of what this game experience would be like before I’d even downloaded it. This echoed many of the sentiments that Nicole Clark mentions in her piece about the rise in popularity of walking sims despite the gaming community describing these games as limited or detractive from traditional games. My high-level experience with playing Dear Esther can be summed up as putting your phone down after a 2 hour TikTok binge and instead picking up a book. I’ll break it down. When I do play video games, I’ll commonly play some kind of shoot-em-up-style game with my friends such as Fortnite. Going from playing Fortnite, one of the most stimulating gaming experiences in terms of all the technical fighting, navigating, and building mechanics (not to mention the dynamics that arise from emotes, skins, and other customizations that afford even higher degrees of expression) to Dear Esther felt like complete 180. The only mechanics in the game are walking and looking. While at first, I felt completely under-stimulated in comparison to playing a conflict-based game, I had no choice but to become enthralled by the story being told. In part, stripping away the fancy mechanics gave me the mental space to imagine. The beauty of TikTok is that its endless content transports you to all these different worlds without nearly any mental effort (no imagination is required). In comparison, when I pick up a book, I play a role in creating and anticipating the world that’s unfolding from page to page. This is the kind of narrative Dear Esther seemed to emulate as I played.

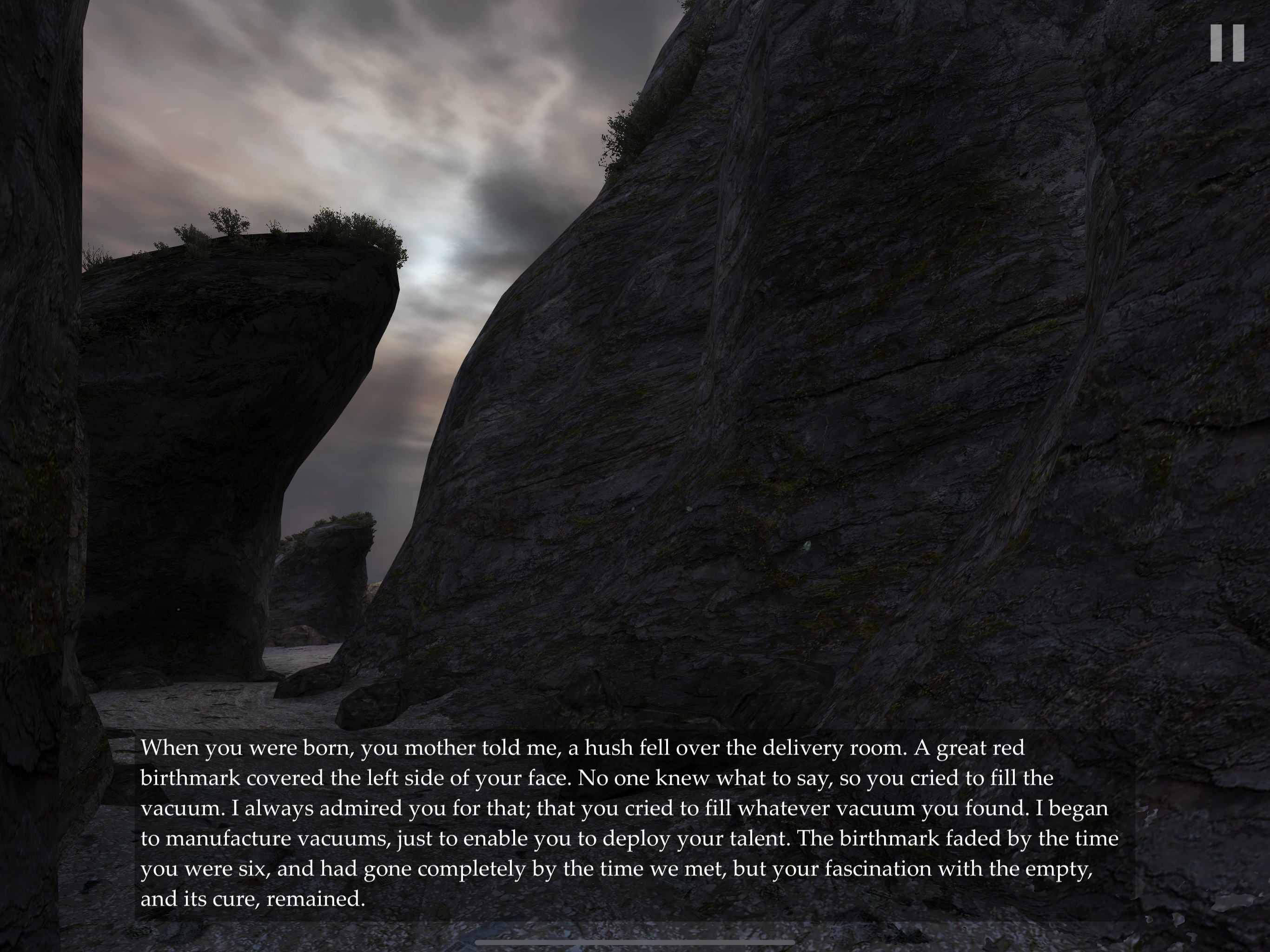

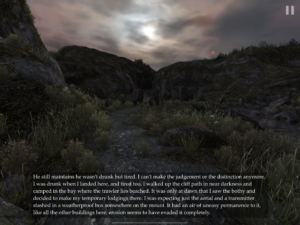

More specifically, Dear Esther uses the geography of the map to obfuscate the story being told. My anticipation of what would be around the next corner of the map helped drive my curiosity about how the narrative would continue to unfold. Without the use of geography hiding physical elements of the map tied to the story being told, I wouldn’t have been nearly as curious to continue exploring. This in my mind was the most important design tactic used to keep the player wanting to walk around the map until the entire story was told. You begin the game at this dock situated at the bottom of a cliff.

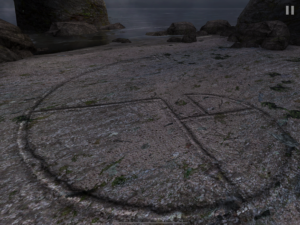

As such, you really only have the option of walking up a trail that meanders up the cliff. At a certain point, the trail erodes and I couldn’t help but slide down the cliff onto the beach below. I thought I might’ve messed up and might have to go back to the start but this was seemingly an intentional design to show me another trail that was on the beach leading to an interesting inscription in the sand and a cave.

At several more points, I thought I was going the wrong way but in every case, there’d always be some interesting geographical feature like a shipwreck, stonehenge kind of thing, or an additional piece of the story that would string me along to explore more. Since you could only walk at a slow meandering pace (and mechanically speaking, nothing else), I found myself more focused on the story being told because I could both read it and listen to it as I was walking, and because it usually took a few minutes before I’d receive an addition to the story, I’d find myself ruminating on aspects of the story I’d just heard and imagine where this might be going.

The parallel between my own meandering mind and meandering body created a deeply immersive experience within the story of Esther.

While I mentioned this briefly in my opening thoughts about the game, the lack of violent mechanics in Dear Esther forced me to interact with the character/world/game fundamentally different than in a mechanically violent game like Fortnite, for example. It feels a bit like a bubble-up effect where the mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics influence your behavior and psychological response to the game you’re playing. More specifically, when I play a game like Fortnite or Apex, the violent MDA of the game primes me to interact with the game more violently, triggering a more excited, fight or flight psychological response as I play that game. On the other hand, when I played Dear Esther, the peaceful, slow, and poetic interactions I was necessitated to have with the game (given its MDA) brought me into a similar headspace of something close to mediation. I don’t have a frame of reference to the psychological research that’s been done in this sphere of understanding human response to different game styles, this was my experience. A cursory search seemed to echo these sentiments where “participants who play a violent game are more aggressive immediately following game play than participants who play a nonviolent game” (Sestir & Bartholow, 2010). I think how these mechanics affect the quality of the story being told is contextual. If a violent story is being told, I would expect there to be violent mechanics implemented to effectively immerse a player into this plot. Similarly, if a non-violent narrative is being told, I wouldn’t expect there to be any violent-mechanics supported in order to tell the story well. If a non-violent story is trying to be told through a game yet you’re able to shoot, kill, attack other characters or players within the game I would advocate that this detracts/conflicts with the story being told (or question if the right story is being told).