Dear Esther, a game created by The Chinese Room and available on PC/Steam and iOS, is a game meant for game enthusiasts who love to uncover stories as they explore their surroundings. In traditional video games, movement is meant to be utilitarian – getting from one combat encounter to another, solving different puzzles, or collecting resources. Dear Esther turns the concept of movement in games on its head. The simple act of walking becomes the main vehicle for the game’s narrative, creating a chilling experience that has players develop the story’s deeper meditations on grief, loss, and loneliness that could not be told through traditional gameplay.

Dear Esther focuses on specific aesthetics when creating its player experience: Discovery, Narrative, and Sensation. It also deliberately reduces the aesthetics of Challenge and Competition. Dear Esther’s aesthetic goals also affect its design, with very minimal mechanics (walking, reading, and looking) generating dynamics (exploration, storytelling through environment) that ultimately create a very contemplative experience.

This game flips the expectations of most video games and leaves players with just one experience: exploring an isolated island. This design choice is not a shortcoming of the game itself; it is the strength of Dear Esther’s storytelling approach. The game reduces the agency of the player to just movement, and this puts the player in the narrator’s shoes as they reflect on their own experiences on the island. Like the narrator, the player keeps moving forward through a grief-stricken and lonely place.

As shown in the screenshot here, the game adds moments of narration that are triggered when the player explores certain locations around the island. The narrator reflects on being “a listless wreck without identification,” which mirrors the player’s own experience of finding their way through the world without standard gameplay markers or tools. There is nothing that gives the player any indication of how “well” they are doing in the game – no health bars, no inventories, no progress indicators – just the feeling of needing to move forward. In this sense, the player, like the narrator, is stripped down to the bare bones of existence on a foreign landscape.

Another aspect of the player experience in Dear Esther that helps tell the story is how the tight movement forces players to interact closely and deeply with the environment. Unlike games that encourage players to rush from one challenge to another, Dear Esther’s slow pace creates a meditative space where players can simply observe and take in their surroundings. The etchings in the ground shown below are meaningful to the player experience because there is nothing else to “do” but take them in.

This shows how the MDA framework functions in practice. The minimal walking mechanic creates dynamics like observation, contemplation, and piecing together the story that supports the aesthetics of Discovery, Narrative, and Sensation. Dear Esther deliberately restricts the actions a player can take to shift focus to the environmental details and the player’s own emotional response.

Many mysterious symbols like this Fibonacci spiral appear throughout the game, but their meaning is unclear. While playing, I wondered what these could have represented. I thought of everything they could symbolize: navigation markers, ritual spaces, indicators of the narrator’s deteriorating mental state, etc. There was no “answer” given for what this represents, but discovering them through exploration created a sense of detective work. I felt like I was engaging with the environment by actively interpreting these landmarks rather than passively being told the narrative.

I viewed this as the game’s way of reframing what player agency means. While the player cannot change the ending of the story through decisions or actions, the process of moving through the space and connecting fragments of the story becomes a way for players to feel a sense of participation in creating the story.

For me, something that struck me about Dear Esther is its complete rejection of violence as a mechanic. Most video games that I am aware of use violence as an important form of interaction with other entities in the game. This could be in the form of combat, destroying objects, or conquering different territories. Dear Esther does not engage with this at all.

In the screenshot above, the player approaches a lighthouse that looks rundown and abandoned. In a conventional game, a lighthouse might contain enemies to defeat one by one or resources to obtain. Instead, the narrator’s memory gets triggered: he discusses the feeling of “giving birth to this island” and leaving “fresh markers” in hopes of gaining a “fresh insight.” I think this peaceful approach and subversion created a different relationship between me (the player) and the environment of the game – one that values its serenity and does not view it as an exploitative landscape like in Minecraft, for example.

The absence of violence also enables Dear Esther to touch on themes that violence might undermine. The game has overarching motifs and narrations on grief, loss, acceptance, and solitude that can only be discussed earnestly in a contemplative space that only a nonviolent setting could provide. Violence would create emotional turbulence – I think it would put the player in a position where they feel they are an agent of change in a narrative that focuses a lot on accepting the inability to change what has happened.

Rejecting violence and providing limited mechanics raises ethical questions about player agency. Most games are built around some sort of fantasy of power. Players get hooked by overcoming obstacles, defeating enemies, and mastering the environment. Dear Esther strips the player of any of these powers, and it creates a very unique environment where all a player can do is continue forward and bear witness to their surroundings and the narrative.

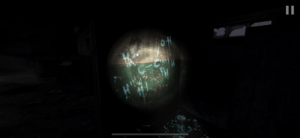

The empty building sequence (shown above) exemplifies this. At the beginning of Dear Esther, the player is placed in front of this rundown shack. In a conventional game, this might be the place where a shootout or combat sequence would happen. To me, this initially represented danger and an obstacle to future success. To me, the writings on the wall of different chemical compounds and illegible chicken scratch represented the narrator’s losing touch with reality. His psyche seemed to be in a tailspin. The player cannot “solve” this space; they can only move through it and experience it through the narrator’s eyes.

My ethical understanding of this is that some experiences cannot be “won” or “mastered”; they must simply be endured. In games with lots of violence, trauma and loss are portrayed as emotions to overcome on the way to success. Dear Esther’s game design made me think that the designers believe that some emotional journeys cannot be resolved through the common narrative of “fighting through them”; they require acceptance and reflection, which is mirrored in how I (the player) interacted with the constraints of the game and accepted my place within them.

In my opinion, Dear Esther does an amazing job of transforming the very basic walking mechanic into a strong device that pushes an emotional narrative. The slow rhythm of walking around, the gradual revealing of the striking landscapes, and the fragmented bits of the narrative all come together to create a powerful, somber story that could not be told through a more traditional form of gameplay.

It seems that Dear Esther required an intentional inversion of the traditional MDA approach. I think that, rather than starting with mechanics that create dynamics oriented around competition or challenge, it first focuses on the desired aesthetic experience (introspection, discovery, acceptance). From this, mechanics can be created that specifically support these goals. This hones in on what Hunicke, LeBlanc, and Zubek call “experience-driven” design, as opposed to feature-driven design.

In Dear Esther, walking is used not just as a mechanic but also as a metaphor for time moving forward and accepting that what’s past is past. However, by using walking as a mechanic, it aims to instill this mentality in the player by embodying a very reflective journey through the narrator’s story.

By removing violence and elements of player agency, Dear Esther encourages us to think about what games can be and how games can tell stories. Maybe the most meaningful elements of game design don’t come from doing “more”, but just by being present and moving forward, which can be emblematic of life itself and useful in teaching its players a valuable lesson.