Critical Play Analysis Week 2: The Dimensions of Deception and Deduction in “Secret Hitler”

Target audience: The game seems to be targeted towards young millennial/Gen Z.

Name of the game: Secret Hitler

Game’s creator: The game is written by Tommy Maranges and designed by Mike Boxleiter.

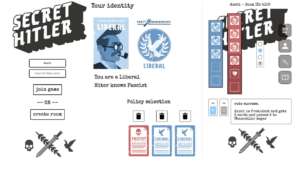

Platform of the game: The game is meant to be played in person, but there is an online adaptation currently that our group used. It lowers the set-up time significantly, allows us to pick a more comfortable location, and doesn’t take away from the in-person interaction factor as we are still face-to-face while using our laptops.

Central Argument:

Secret Hitler facilitates fellowship and a smooth bonding experience with players by 1) creating a low barrier-to-entry to inexperienced players, and 2) forcing players perform tasks that give clues to everyone involved, thus always propelling the game forward, as opposed to other social deception games where everyone can bluff to a stalemate. Mafia comes to mind in this case, especially with a big group of strangers, where the game is at a much higher risk of dying down. In contrast, Secret Hitler always operates like a well-oiled machine with constant incentives to participate.

Analysis:

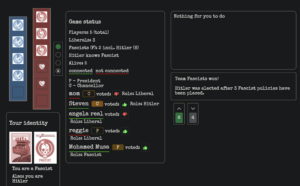

Secret Hitler allows for smooth gameplay and bonding through a combination of impressively thought-out design choices. The game has a fairly simple gameplay and set up (the online version we played) – players take turns drawing and playing cards to either pass liberal policies or fascist ones, with the fascists secretly working together to enact fascist policies and get Hitler elected Chancellor. Once this happens with three fascist policies already having been passed, the fascists win. If 5 liberal policies are passed or Hitler is assassinated, the liberals win. In contrast with a game like mafia with numerous roles, tasks, and boundaries (day/night, etc.), this game’s simple structure makes it easy to learn and jump into, even for inexperienced players.

On top of that, it forces participation and gives constant clues through analysis of the selection of policy cards players choose, and the results of elections and their public votes. Unlike games like Mafia where players can stay silent, everyone has to take a turn drawing and playing policy cards in Secret Hitler, which provides ample time for fascists to stage scapegoats or make what I can only describe as spectacular slip-ups. The election and policy enactment results also provide a steady drip of information for players to discuss and analyze.

Compared to similar social deduction games, these mechanics help Secret Hitler avoid stalling out or getting bogged down. The game keeps moving forward as players are forced to take actions, fueling ongoing discussion and deduction. While Mafia relies heavily on open-ended discussion that can not lead anywhere, Secret Hitler gives players concrete events to debate and interpret.

However, there do exist some limitations. For players who dislike lying/deception, the game may come off as uncomfortable. Another limitation is that I can definitely see the simplicity backfiring, especially with smaller groups as we’ve noticed during our critical play that it becomes easier over time to figure out people’s tells and how they behave given different roles.

Learning:

Secret Hitler’s design aligns well with concepts from the MDA framework (mechanics, dynamics, aesthetics). The game’s mechanics, like the secret role cards and the policy deck, create dynamics of hidden information, deception, logical deduction, and voting. These serve as breeding grounds for tension, paranoia, and catharsis when the fascists are uncovered or Hitler is assassinated.

The game’s formal elements also contribute significantly to the play experience. It has fairly simple rules that are easy to learn (low barrier to entry). The shuffled policy deck also gives it just the right amount of randomness where it’s enough to facilitate strategy but not so much that skill doesn’t matter. In addition, there is somewhat of a built-in catch up mechanism through the ratio of liberal to fascist policies that keeps the game competitive. The secret roles and hidden voting provide the core player interaction of deception, deduction, and the occasionally hilarious freudian slip. All these formal elements work together to make Secret Hitler function pretty smoothly without too much reliance on the improvisation of the players, which I find to be incredibly refreshing. I also believe that the provocative theme helps make the game more memorable and talked about, and leads to the formation of inside jokes that promote group bonding.

Formal Elements:

Players: Player vs. Game, Player vs. Player, Multilateral competition (3+ players directly competing, like in Monopoly), Unilateral competition (2+ players competing against one player), Team vs. Team

- Team vs. Team

Objectives: Outwit, Solution, Exploration, Construction, Forbidden act, Rescue/Escape, Alignment, Race, Chase, Capture

- Outwit

Outcomes: Zero-sum, Non zero-sum

- Zero-sum

Procedures: The main procedures are responsibilities of the President and Chancellor where they must work together to enact a policy, and the elections where all players vote on who those two are.

Rules: There are rules for setup (how many fascists for each player count, how many policies in the deck), selection and passing of policies (the President draws three policies, discards one, Chancellor enacts one of the remaining two), the election (players vote yes or no, if no then the next player becomes President, if three failed elections then the top policy is enacted), and the actions the President can take after certain fascist policies are enacted.

Boundaries: General “Magic Circle” boundaries are the venue chosen, the imaginary role-playing essence of the game, and the laptop screen given that we played the online version. The other boundaries in Secret Hitler are the number of liberal and fascist policies that can be enacted before the game ends (5 liberal policies for a liberal win, 6 fascist policies for a fascist win, or 3 fascist policies plus Hitler being elected Chancellor for a fascist win). Another key boundary is the hard limit on the number of fascists in the game based on the player count.

Mechanics:

Rules and systems that create the play we experience (ie the math for shooting in a game) For example, the mechanics of card games include shuffling, trick-taking and betting ñ from which dynamics like bluffing can emerge.

- Shuffling cards when you run out, voting, picking policies.

Dynamics:

The actual experiential play those mechanics some together to create (running and gunning gameplay). Dynamics work to create aesthetic experiences. For example, challenges are created by things like time pressure and opponent play. Fellowship can be encouraged by sharing information across certain members of a session.

- Deception, deduction, and social influence

Aesthetics:

- The main aesthetics in Secret Hitler in my opinion are Fellowship, Competition, and to a lesser extent, Narrative (the story arc of Hitler’s rise or fall) and Fantasy (the role-playing element of pretending to be a 1930s German politician).