I played Blood on the Clocktower created by Steven Medway and The Pandemonium Institute. The only platform is in-person. The target audience of the game is teenagers and adults since the complexity of the rules, including the narrator, require an extensive knowledge of the rules and a strong foundation in other social deduction games.

Blood on the Clocktower emphasizes social deduction through its intricate role abilities, omniscient narrator, and voting process which create an engaging experience that forces players to communicate in secrecy to succeed.

Players assume hidden roles within a village, each role possessing unique abilities and win conditions. This complexity enhances the game’s social deduction aspect by requiring players to deduce others’ roles based on their actions and interactions as the main objective. Players tend to hide their roles and break off into smaller groups to strategize and share information in secret. Often they form alliances and deceive others by lying about their own role to stay alive in the game longer. While this element of deception creates anti-fellowship, once you can verify who your teammates are, you’re incentivized to cooperate and feel triumph when you win and outsmart the other team.

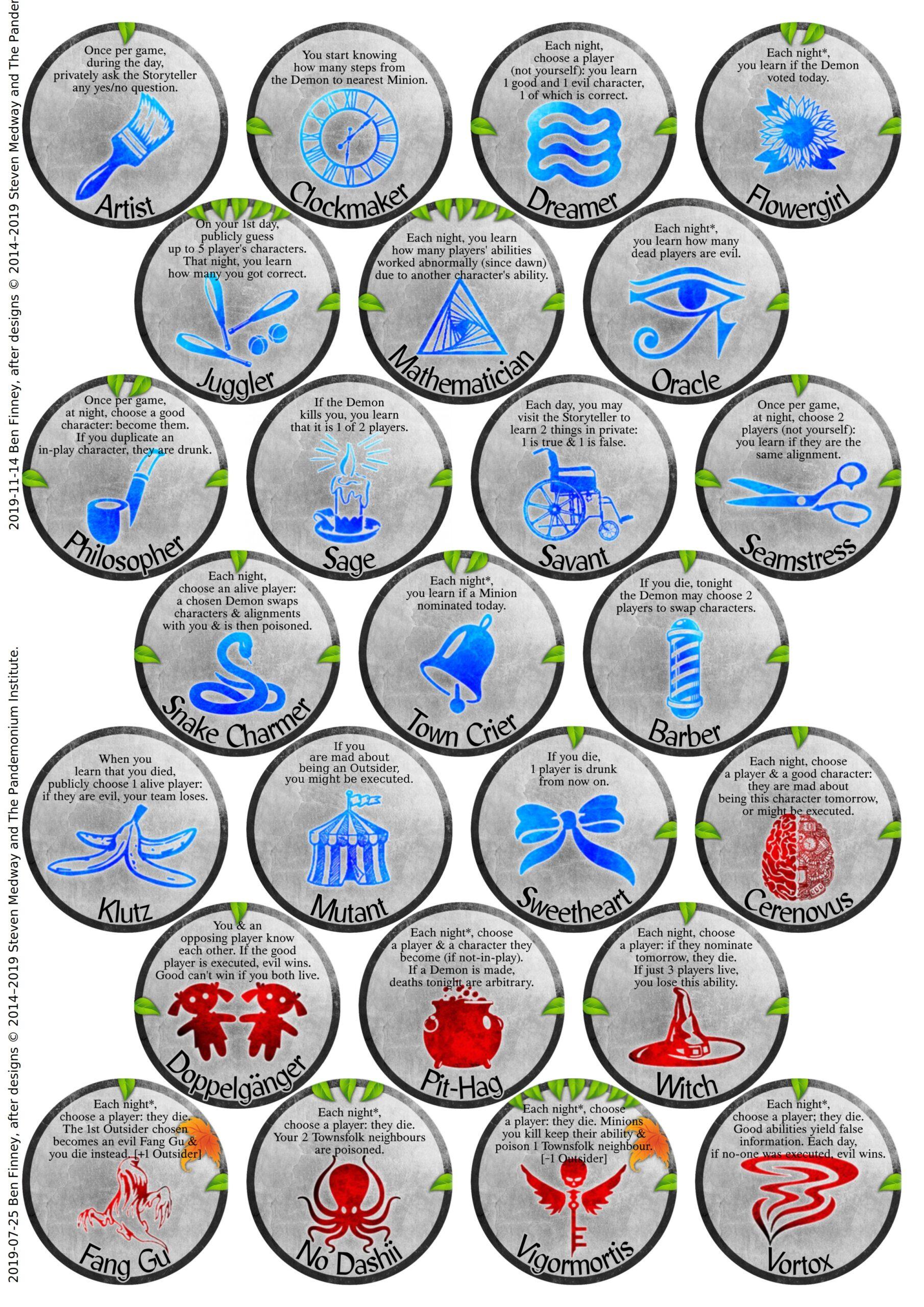

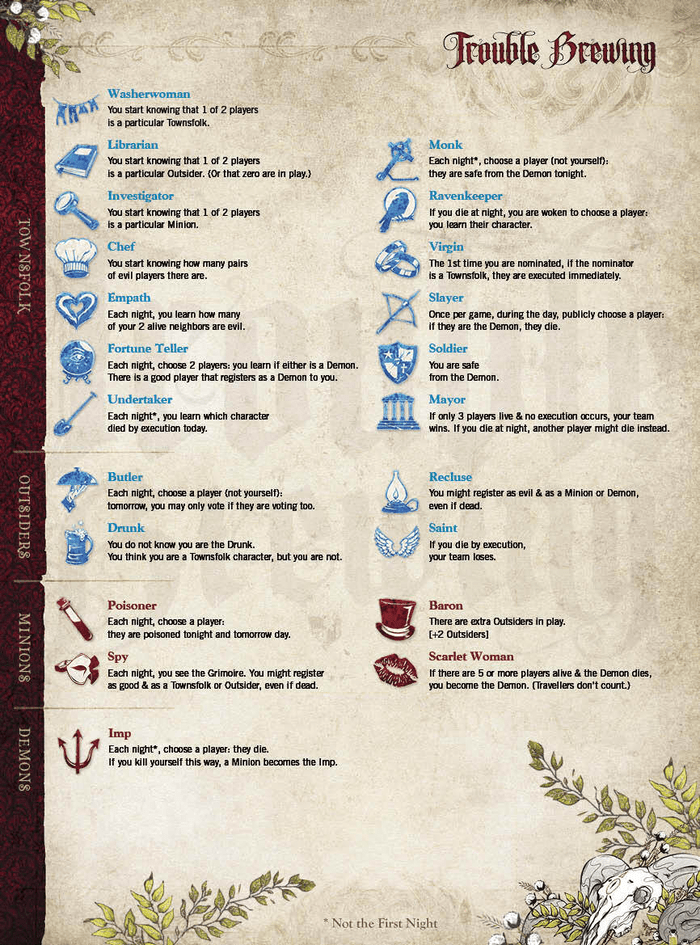

Since the game is so dense, procedures are a huge part of keeping the integrity of the game. At all times, every player is able to reference a sheet of all the roles and their abilities.

This keeps the game in motion since they can always check information they receive throughout the game and compare it to the sheet to verify if someone is lying or not. However, this also introduces a skill imbalance into the game between new players and experienced players. In the game I played, the new players spent most of their time referencing this sheet and accidentally revealed valuable information (i.e. they were a demon), while experienced players quickly weeded out many roles since they knew the degree of secrecy that should be kept.

The biggest element of the game is ensuring that the rules are followed. This is done through an omniscient narrator who acts as the moderator of the game, keeping track of everyone’s roles and conversations through the game board.

Since they act outside of the boundaries of the town, during the game it is pretty common for players to have 1-on-1 conversations to clarify their role or use their abilities. Players are expected to blindly trust that what the narrator says is fact. The heavy reliance on a knowledgeable moderator can sometimes lead to confusion or frustration if rules are not communicated effectively. The “magic circle” can also be broken if the moderator’s biases interfere with their impartiality. For example, in the first game, the narrator activated the wrong abilities since the rules were not entirely clear, which led everyone to believe incorrect information as the truth. He also would sometimes provide specific information because “[he] felt bad” even though it would provide an unfair advantage. Implementing stricter guidelines for moderators could help maintain the integrity of the game’s narrative and ensure a fair playing field for all participants. That being said, the narrator is the sole person in charge of storytelling, crafting an immersive experience that is fun for all players because the story is inherently unique to that game. Since the narrator doesn’t have a script, everything that is said is a new storyline so it’s easy to become invested in the narrative.

Lastly, the game’s reliance on nominations to kill players introduces another dynamic where players throw around accusations to manipulate voting outcomes. This creates the biggest formal element, conflict, since the game is based in deception from the beginning. During the execution process, the quick turnaround between deliberations, nominations, voting, and then execution forces people to say whatever they can to be the most convincing. Not to mention, dead players can also participate in the conversations and have one dead vote, so they end up becoming a huge deciding factor at the end of the game where the last execution decides which team wins.

Comparing Blood on the Clocktower to other social deduction games, the unique storytelling and responsibility given to ALL roles sets it apart. While games like Werewolf or Mafia focus on interactions between players alone, Blood on the Clocktower introduces additional layers of strategy through interacting with the narrator, and also having side conversations in private. There is never a time in the game where a player will feel “useless” or like a sitting duck. There will always be people talking, activating abilities, participating in executions, or piecing together information to identify the demon. Since this game can only be played in-person, it really forces you to maintain a great poker face and analyze people’s speech and body language.