two houses

One moment, your marriage is ending. The next, you wake in a different world where every tragedy reflects another. Every choice brings you closer to heartbreak, yours or theirs.

Play the game here! https://krvstcl.itch.io/two-houses

(spoilers ahead! highly recommended to play before reading!!)

Content Warning: This game contains themes of abusive relationships, miscarriage, grief, relationship conflict, and canonical Romeo and Juliet content including death and suicide.

Premise/Overview

two houses is an interactive fiction game that explores themes of toxic love, personal growth, and the complexities of relationships through the lens of Romeo and Juliet. The player will take on the role of Vincent, an about-to-be divorced 31-year-old who gets mysteriously transported into Shakespeare’s Verona after his wife throws a pan lid at his head. To return home, Vincent must guide Romeo and Juliet toward a healthier relationship—one that doesn’t end in tragedy…

The premise emerged from thinking about how we romanticize destructive relationships in classic literature. What if someone from our modern era, carrying their own relationship baggage, had to confront the toxicity of Romeo and Juliet’s whirlwind romance head-on? The game explores how our actions, or inaction, shape the relationships around us, and how helping others can help us see our own blind spots. The core themes revolve around distinguishing toxic love from healthy love, understanding how our choices ripple outward to affect others, using external conflicts to understand our internal struggles, and questioning whether we can truly fix what we’ve broken or if we must simply accept and learn.

My main goal was to have players become interested in Vincent’s marriage and saving Romeo and Juliet’s relationship, seeing the parallels between them. I wanted players to feel invested enough in the story that they’d want to replay to discover the different endings, not just out of curiosity about game mechanics, but because they cared about the characters’ outcomes. Through ten playtests and three major development phases, this goal evolved and sharpened, ultimately resulting in a game that asks players to confront difficult truths about love, agency, and personal responsibility.

[Image of two houses title screen.]

Story Structure

two houses features three distinct endings, reached through a combination of major and minor choices throughout the narrative. The branching structure deliberately includes meaningless choices that feel significant but don’t alter the outcome to get the player comfortable with making decisions. This design choice, which initially frustrated early playtesters, eventually became thematically important as players experienced how some relationship moments (especially flashbacks) are already determined by the character’s earlier actions.

The game is structured around five acts, each corresponding to key moments in Shakespeare’s original play, but with opportunities for intervention and alteration.

- Act I, “The Capulet Ball,” serves as the tutorial loop where Vincent wakes up mid-party and must decide how to facilitate Romeo and Juliet’s first meeting. The major branch point here asks whether you help Romeo approach Juliet naturally or intervene more directly, setting the tone for your approach throughout the game.

- Act II, “The Secret Marriage,” introduces Friar Lawrence, who is an older “wise” character who advises Romeo and Juliet. In this act, Romeo and Juliet get married in a secret wedding. Though Vincent doesn’t have direct impact here, his actions determine the later choices available to him.

- Act III, “The Duel with Tybalt,” represents the game’s key moral dilemma. Players face a time-pressured decision about whether to encourage Romeo to show mercy, avenge Mercutio, or let fate decide. This act underwent the most revision during playtesting, as I had to make sure no choice felt obviously “correct” while still having meaningful consequences.

- Act IV, “The Friar’s Plan,” leverages the player’s knowledge that the fake death scheme will fail in the original play.

- Act V, “The Tomb,” presents the final moral choice that determines both Romeo and Juliet’s fate and tests Vincent’s understanding of love. The player’s choices leading up to this moment decide what ending comes out of this.

Map:

[Diagram showing how specific choice combinations lead to each ending]

HD Version: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1LDPEXhIedK_sEV5I-t2YPE6GsS4fGWJg/view?usp=sharing

Iterations:

All Playtests linked here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/18sGIR8aN7a_YB6wdJCDtCWf1v6lUPVF5?usp=drive_link

Phase 1 – Paper Prototype and Concept Testing

two houses went through three major development phases and ten playtests that fundamentally shaped the final experience.

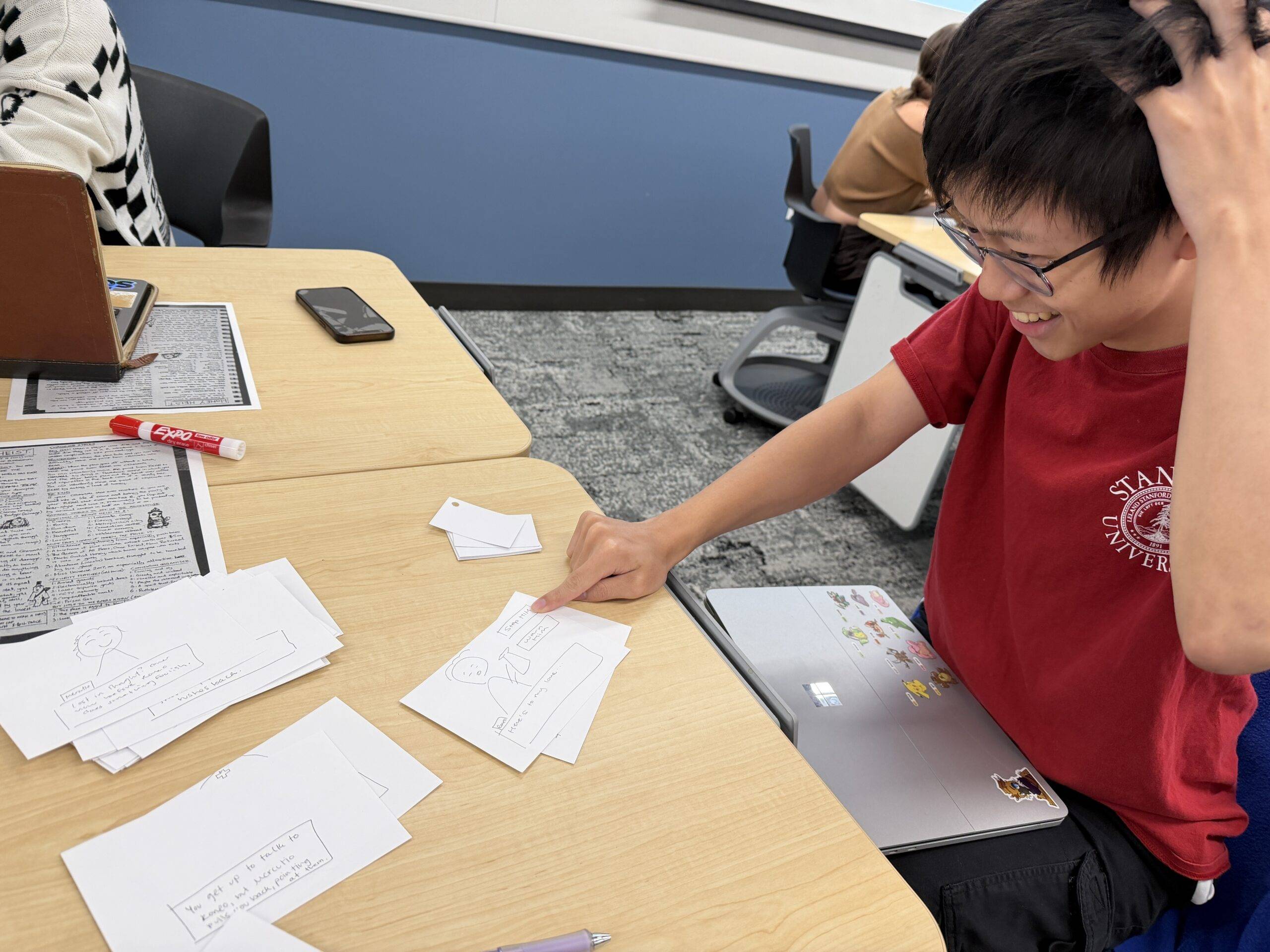

My first playtest was with Lucas, a college-aged man who is familiar with interactive fiction but didn’t know Romeo and Juliet well.

The playtest immediately identified a critical issue that would shape the entire development process. Lucas loved the core concept, the idea of a divorced father trying to fix a toxic fictional relationship resonated emotionally, but he noted that choices felt less impactful than expected. More surprisingly, he pointed out that “the paper prototype actually signals that my choices don’t matter much because there are only so many papers.” This was a revelation I hadn’t anticipated: the format itself was undermining player agency before they even engaged with the content. The physical limitation of the paper prototype made the boundaries of the narrative visible in a way that destroyed the illusion of meaningful choice.

Lucas also identified several narrative gaps that needed addressing. He wanted more context about why Vincent exists in this world since the magical transportation felt arbitrary without clearer rules. He also wanted more clear differentiation between flashbacks and the present timeline, as the paper format made temporal shifts confusing. Most importantly, he felt character motivations were underdeveloped and he couldn’t understand why Vincent would care enough about fictional characters to actively work to save them rather than just trying to escape immediately.

[Photo of first playtest with Lucas]

These insights led to the first major round of revisions. I rewrote Vincent’s transportation to Verona with clearer supernatural rules, establishing that he’s caught in a loop and can only escape by “fixing” the story. I also added more morally ambiguous choices where neither option feels “correct,” moving away from obvious good/bad dichotomies. I expanded character backstories extensively, particularly Vincent’s relationship history, developing specific incidents that would parallel the Romeo and Juliet plot. Most significantly, I began mapping the story out so that I could better playtest the branching narratives in a way that wasn’t obviously limited by papers.

Phase 2: Digital Prototype (Figma flow)

After incorporating Lucas’s feedback, I created a digital prototype in Figma to better visualize the branching structure and test some different narrative paths. This phase allowed me to experiment with a “relationship meter” that tracked choices that lead to healthy or toxic relationships, and also whether the branching choices led to a more interesting story.

The second playtest was with Julia, a college-aged woman who does not typically play interactive fiction games but loves romance stories. This player said that the dialogue pacing felt “just right” since clicking while reading through felt natural to her. However, she was initially confused about the setting until the conversation with Mercutio clarified where and when the story was taking place. This indicated that the opening needed stronger context clues to orient players immediately. Julia also felt that the transition from modern day to Verona was too abrupt, lacking the emotional buildup that would make the displacement feel significant. Her feedback led me to expand the opening sequence with Vincent and his wife, adding a bit of a longer argument about their relationship problems before the magical transportation occurs.

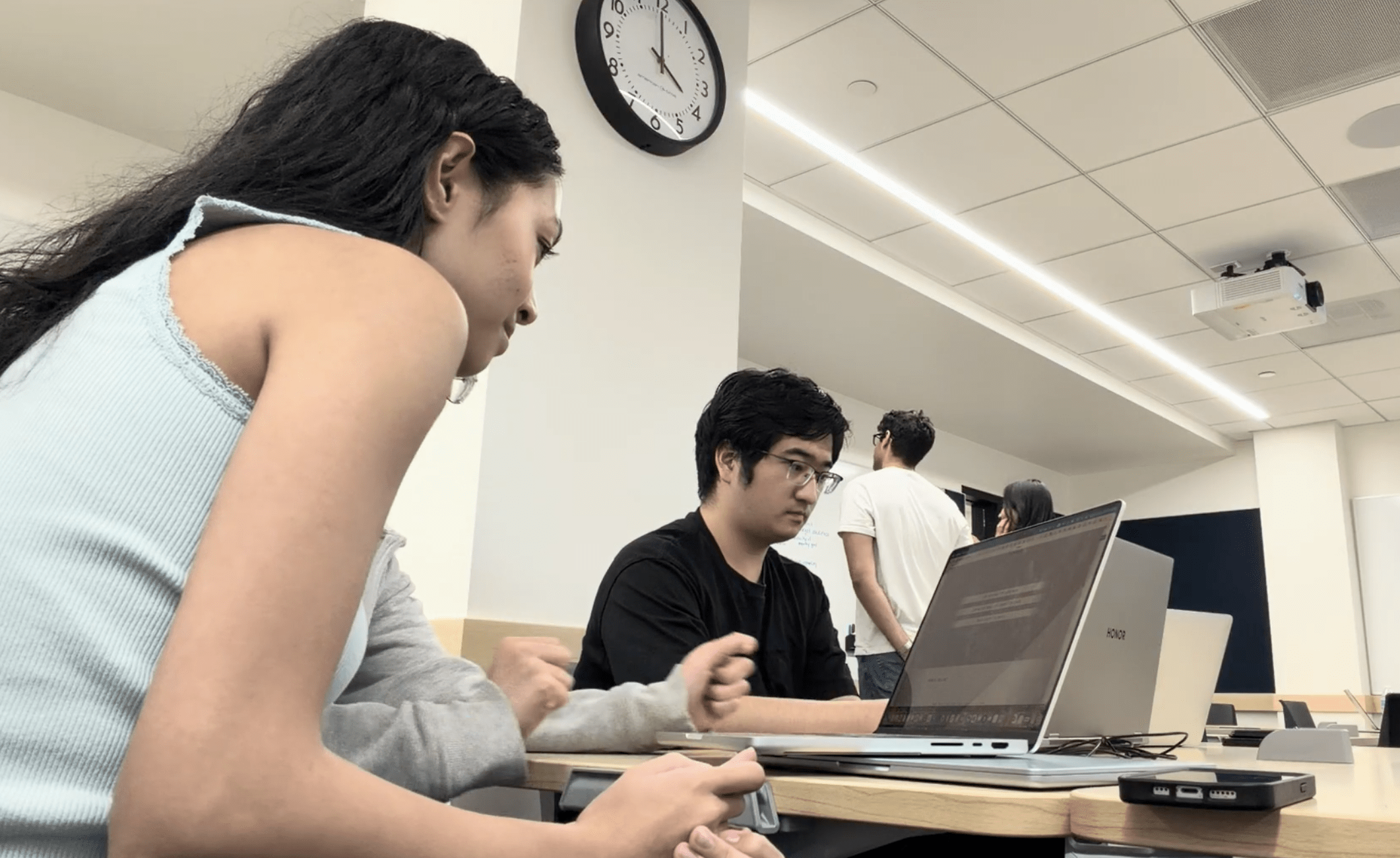

[Image from Julia’s playtest.]

Phase 2 Changes: After my second playtest, I ported all of my choices and script onto Ren’py, so that I could start testing a format that was closer to what the final version would look like. In order to help add life to the game and address some of the confusion people were having, I also added visuals to differentiate the two worlds. Flashback scenes use a darker, apartment setting that evokes the coldness of Vincent’s home and the fleeting qualities of memory, while Verona shifts between light backgrounds and dark ones to signal emotional stakes. I found that the difference between flashback and present day backgrounds helped players immediately understand the context and emotional weight of each scene without relying solely on words.

Phase 3: Ren’Py Implementation

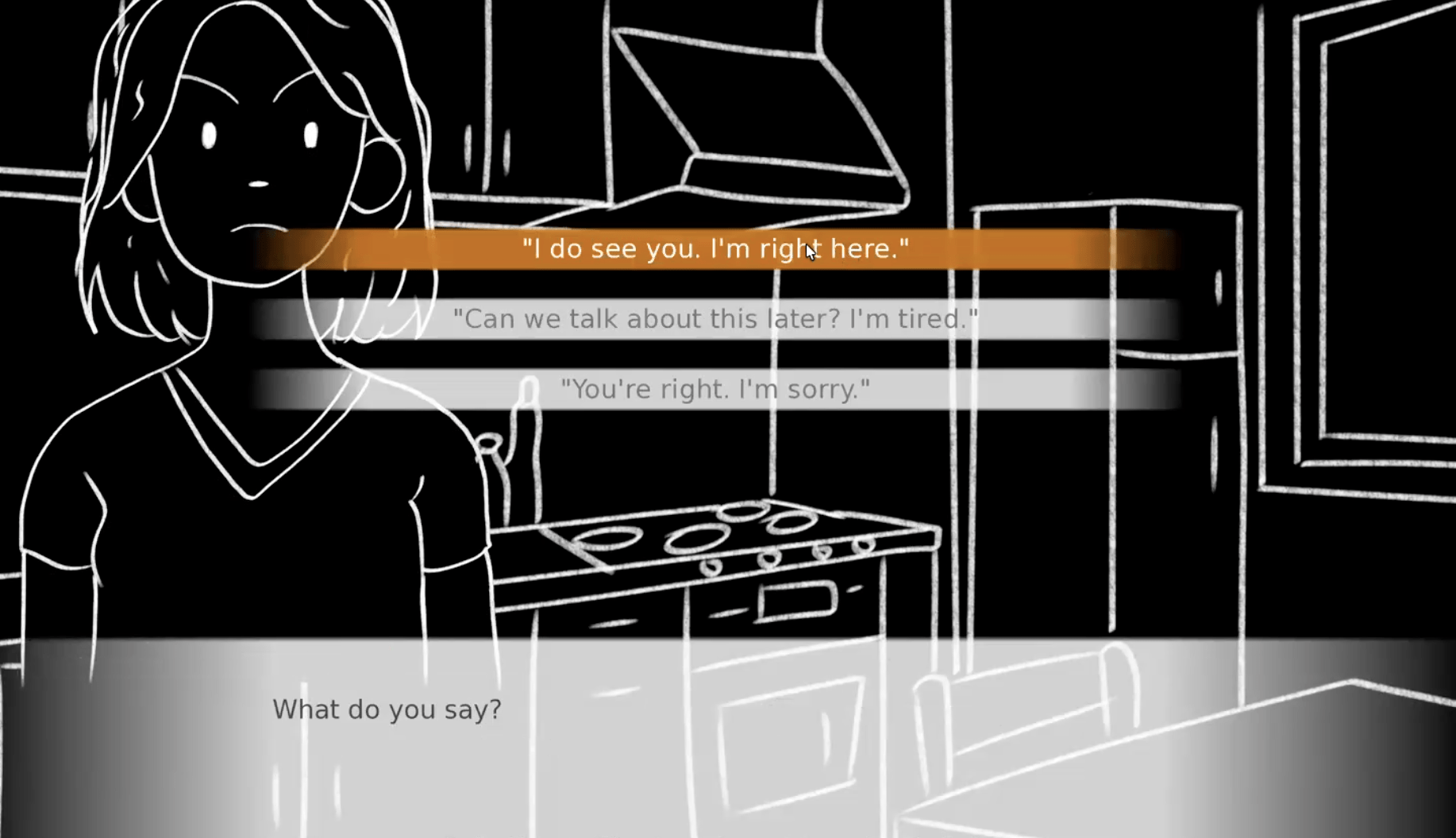

[Image of a flashback scene.]

[Image of a scene taking place in Verona.]

Character positioning and expression add another layer of interactivity beyond text. Rather than relying solely on dialogue, I created character sprites that react to choices. For example, Romeo’s expressions change based on Vincent’s advice, and Sarah’s face changes depending on the gravity of the scene and Vincent’s responses. These visual cues reinforce the consequences of player decisions.

[Image of Sarah crying.]

The third playtest was with Angela, a college-aged woman who loves world-building games like Minecraft and Stardew Valley and enjoys romantic comedies. This playthrough revealed both significant strengths and some technical issues. Angela immediately connected with the visual presentation, saying “the visuals look amazing, having characters and backgrounds made it feel alive.” She particularly liked seeing everyone on screen simultaneously, which made her feel connected to the dialogue in a way that pure text couldn’t achieve. This validated the decision to invest in visual assets rather than relying on text-only presentation.

However, Angela also identified several problems that were breaking immersion. For example, characters sometimes overlapped in group scenes making it confusing who was speaking at any given moment. There was also a point where the text indicated “music plays,” so she expected to actually hear something and the silence felt empty and didn’t contribute to the atmosphere I was trying to create. She also notes that some dialogue options felt too similar to each other, leaving her uncertain what differentiated them or how each would meaningfully change the story. Most critically, she wanted stronger reactions after big choices, noting that “right now it moves on too fast, so it’s hard to feel the consequence.” This feedback highlighted that I was providing choice without adequate feedback, leaving players uncertain whether their decisions mattered.

[Photo from Angela’s playtest, where she finds out about the “supernatural” force keeping Vincent in Verona. ]

This playtest prompted significant changes as well, since I adjusted character positioning and sizing to prevent overlap, creating clearer visual staging for group scenes. I began planning audio implementation, researching period-appropriate music and ambient sounds. I consolidated similar choice options into more distinct alternatives, ensuring each choice represented a genuinely different approach or philosophy. Most importantly, I added pause moments and visual/textual reactions after major decisions—brief scenes where characters process what just happened, giving players time to feel the weight of their choices before the story rushes forward.

The fourth playtest was with Madison, a college-aged woman who is very familiar with the isekai genre, enjoys RPG games, and loves romance. Madison’s responses revealed both what was working emotionally and what needed deeper development to achieve the game’s goals. Specifically, he expressed genuine satisfaction at reaching the happy ending, saying she was “happy that I got the happy ending, very much enjoyed the art.” More tellingly, she felt frustrated when “Romeo wasn’t listening, Romeo come on man, I’m trying to help you here, about to give up.” This frustration indicated real emotional investment (yay!) she cared enough about the outcome to feel genuine annoyance at Romeo’s stubbornness.

However, Madison also identified crucial narrative problems. She noted that the story “narratively doesn’t make sense, unless it’s Groundhog Day,” pointing out that the time-loop/reset mechanic wasn’t clear enough in the presentation. She felt the ending was “too easily forgiven, more choices to see if you actually learned from mistakes,” indicating that Vincent’s arc felt incomplete. Specifically, she observed that “Romeo going from one girl to the next is toxic, expand on that,” recognizing that the game was identifying problematic behavior without adequately addressing it. She wanted to see Romeo become “a better person” over the course of the story, not just survive the plot.

Madison also had significant feedback about representation and pacing. She wanted Juliet’s perspective featured more prominently, noting that the story was overwhelmingly focused on male characters’ experiences and decisions. She felt there was “a lot of dialogue between when choices were made,” with some choices feeling important while others felt like an “illusion of choice.” This distinction helped me understand which types of choices players found meaningful versus which felt like busy work.

[Photo from Madison’s playtest, Capulet party background is still missing here.]

The fifth playtest was with Ryan, a college-aged man who enjoys light-hearted, comedic, role-playing games. Ryan pointed out a lot of fidelity issues such as characters overlapping which caused confusion about who was speaking, and missing backgrounds. He also noted that while some context from the play was nice and added to the immersion, there were some messages like “the night they both end up dead” that felt “too on-the-nose” breaking the fourth wall in a way that felt clumsy. However, Ryan seemed to really enjoy meeting new characters and the consequences of the different choices, exclaiming “I didn’t know that was going to happen! I thought we were lying about Rosaline becoming a nun” [7:17].

[Image from Ryan’s playtest.]

The sixth playtest with Amaru who loves a good romance and likes role-playing games and has read Romeo and Juliet in the past. Up until this point, most paths led to tragedy or bittersweet outcomes, and Amaru’s feedback made clear that players needed more agency to create genuinely good outcomes, not just “less bad” ones.

Phase 3 Changes: Overall, This feedback led to a major round of revisions that reshaped the game’s second half. I rewrote the ending to introduce new choices to breakup long dialogue, and also required some choices at the end so Vincent could demonstrate actual growth through actions rather than just expressing regret through dialogue. I added multiple new scenes from Juliet’s perspective to balance screen time. I also corrected all background and sprite associations, creating a detailed spreadsheet to track which assets should appear in which scenes. I rewrote the tomb scene for clarity, adding more specific stage directions and emotional points Most importantly, I adjusted character sprite emotions to match scene context

One thing I chose not to add, was extra dialogue that clarified the supernatural rules governing Vincent’s presence in Verona. Though some people mentioned that it was confusing to understand how the character got to Verona, it seemed to take other players out of the immersion of the game.

Also, while some players seemed to like the ambiguous endings and how it loops back to the beginning, it became clear that this was not enough to show the player the consequences of their negative actions. Thus, I chose to add in a concrete negative ending that prompts the player to replay the game with different choices.

Phase 4: Refining Prototype

I then playtested with Ngoc, who is college-aged and familiar with the isekai genre and interactive fiction games. Ngoc seemed to get more invested in the different characters. For example, when Romeo quickly moved from Rosaline to Juliet, Ngoc exclaimed “Romeo that’s an L, why are you cheating? [6:20]” This reaction showed that players were noticing the problematic aspects of Romeo’s behavior, which was exactly what I wanted. Ngoc mentioned wanting the pregnancy scene to have music that then cut to silence to punctuate the loss of the miscarriage. When making cruel choices, Ngoc said she felt like “a horrible person” and wanted clearer moral framing, indicating that the game was successfully creating emotional investment but maybe too much guilt.

[Photo from Ngoc’s playtest]

She suggested showing Vincent missing his wife through observing couples in Verona, creating environmental storytelling moments. She wanted Romeo to ask Vincent about his romantic history, creating an opportunity for direct dialogue about love and relationships. Most movingly, she noted that the flashbacks were “really meaningful” but wanted them expanded, seeing them as the emotional core of the game.

The eighth playtest with Brydie, who is a college-aged woman familiar with episodic games like Episode, has some classic literature background, and was very familiar with Romeo and Juliet. Brydie had a lot of questions about Vincent’s place in the world and was “wondering if Romeo knew Vincent” since that impacts the choice she wanted to pick. She was also confused about Vincent’s supernatural status and wanted more clarity on whether Vincent was an observer or participant. She questioned why Vincent specifically could see and influence certain events, pointing to unclear magical rules.

This player also had strong positive emotional responses and mentioned how she really liked the vacation flashback scene and kept saying it was “so sad, the little tears” [16:23], found the fourth-wall breaks funny and appreciated them, and noted that flashbacks were what she “enjoyed the most… likes slice of life. [34:37]” She deliberately chose the “doomed” path to see consequences, indicating genuine curiosity about the branching structure. A comment that stood out is that she wanted “more flashbacks and a bit more of Vincent’s inner thoughts [17:28],” which showed that some of the more intimate scenes were resonating more strongly than the dramatic Shakespeare plot moments.

[ Photo from Brydie’s playtest.]

Following these playtests, I rewrote the opening to clarify Vincent’s supernatural nature and limitations, adding dialogue clarifying what he can and can’t do. I strengthened environmental descriptions to ground his position relative to other characters and introduced new flashback scenes at major decision points sort of like emotional rewards for the player. I also reworked the miscarriage scene to balance Vincent’s grief with Sarah’s pain, revealing how his inability to process loss strained their relationship. I also implemented more choices in the final flashbacks to increase embodiment and strengthen the player’s empathy for Vincent in the sad moments with Sarah. Ngoc’s suggestions also led to adding strategic silence and music cues as I started working with audio to create stronger emotions. I expanded Vincent’s internal monologue about missing Sarah, adding observations about couples, families, and domestic moments that trigger happier memories. I also created a new dialogue branch where Romeo explicitly asks about Vincent’s marriage, allowing the player to reflect on their own relationship while advising Romeo.

Phase 5: Final Polishes

By this point in development, most major narrative and technical issues had been resolved, and these sessions served primarily as confirmation that the game was functioning as intended.

A few different fidelity issues came up, such as: repetitiveness of music, wanting to see more of the wife Sarah and happier memories. Thus I made a lot of final polishes changing the music, and updating some fo the flashbacks to include some happier moments. There were some comments about wanting to see more of the Montague and Capulet family rivalry backstory and who Count Paris was and why he was so set on marrying Juliet, but because of the time and scope of this game and its focus on the relationships, I chose not to move forward with this feedback.

[Image from playtest session with Nathaniel.]

[Screenshot from playtest recording with Daniel.]

Reflection

Developing two houses taught me that interactive fiction isn’t just about offering choices, it’s about making players care about the consequences of those choices. Early playtests revealed that I’d focused too much on the branching structure and not enough on emotional investment. Players needed to understand and empathize with Vincent before they could feel the weight of his decisions in Verona. This seems obvious in retrospect, but as I was designing it was easy to assume that interesting mechanics will naturally generate engagement. They don’t.

I also learned about the importance of specificity in character writing. The early dialogue felt too modern, so I started using more renaissance/fantasy speech from the Romeo and Juliet play and movies, which players found more immersive. By looking into old Shakespearean english but not overdoing the “thee/thou” kind of words that makes some of his dialogue unreadable, I was able to find a voice that felt appropriate for the game. Character-wise, Vincent’s voice evolved from a generic “divorced dad” to someone who is on the brink of ending his relationship, who genuinely loves his wife but shows it through material gestures (buying gifts, working overtime to provide) rather than presence. He wants to be a good person but often takes the path of least resistance, which is why small relationship failures compounded over time

The choice system also required significant refinement based on playtest feedback. The “meaningless choices” that frustrated Lucas in Playtest #1 eventually became thematically important, but only after I made the meaningful choices more obviously impactful by contrast. Some choices in relationships genuinely don’t matter because the outcome was already determined by earlier actions. Having players experience this in the game by making a choice and then learning it couldn’t change an already-broken situation helped to reinforce the message about how small relationship failures compound over time. But this only worked after I ensured that other choices had visible consequences, establishing that the game could respond to player agency in important situations.

If I were to expand two houses, I’d add more branching in Acts I and II to create greater variability in how players reach the later acts. Currently, the early game is relatively linear since I wanted it to follow 5 major cannon events in the play, with major branching occurring primarily in Acts III-V. This was a practical decision but it means that players replaying the game experience very similar openings even when heading toward different endings. I’d love to create multiple different ways for Romeo and Juliet to meet, each establishing a different dynamic that carries through the rest of the story.

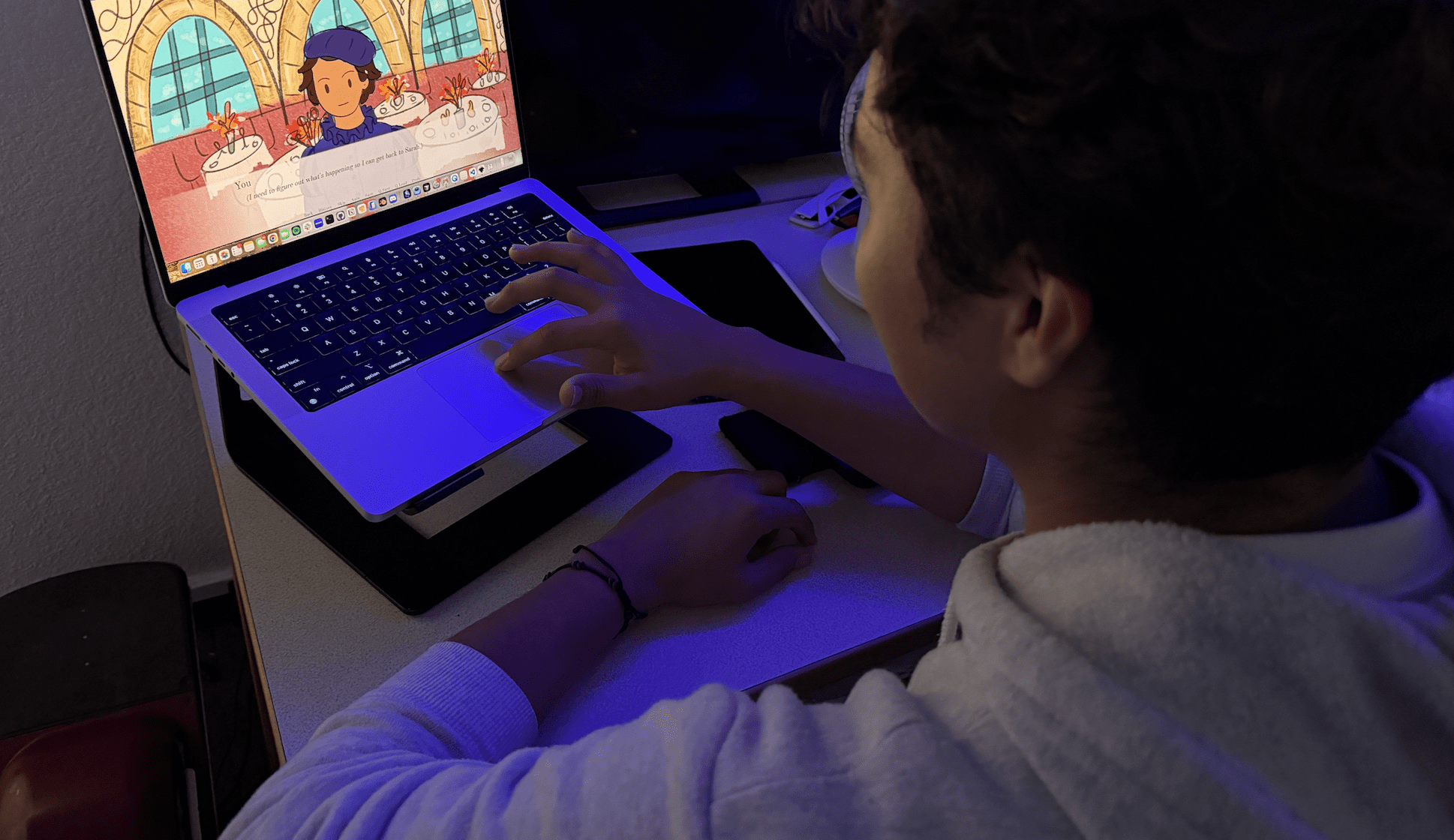

[Final game screenshot from one hopeful ending.]

Ultimately, I wanted this game to build empathy through character vulnerability. Vincent doesn’t have all the answers, he hesitates, overreacts, and fails sometimes despite good intentions. By placing players in the role of someone trying to be a good person but never fully in control, I wanted them to feel the tension of caring deeply while being powerless to fix everything. You can see what needs to happen in flashbacks but can’t always make it happen, mirroring the frustration of watching someone you love make choices you can’t prevent. That powerlessness is intentional and teaches that supporting others isn’t necessarily about necessarily telling them what to do all the time, but about listening and helping them find the right path themselves.

Based on playtest feedback, the game was able to create that emotional investment and empathy for the characters. Multiple playtesters expressed genuine frustration at character stubbornness, relief at reaching positive endings, and sadness at tragic outcomes. Most importantly, a lot of players mentioned unprompted connection to their own relationship experiences and said things like “this moment reminded me of myself” (Daniel [32:28]) or “that’s so real.” As players grew attached to Vincent and to Romeo and Juliet, I found that a lot of them found aspects of themselves in a character and could connect experiences to their past relationships, which was an interesting effect I didn’t expect given characters are much older and younger than my playtesters.

Acknowledgments: Huge thank you to all my playtesters for their time, honesty, and feedback! <3 Lucas, Julia, Angela, Madison, Ryan, Amaru, Ngoc, Brydie, Nathaniel, Daniel, and others who contributed to making this game better. Special thanks to the CS377G teaching team for guidance throughout the development process.

Wow, Krystal! I had so much fun playing your game! I was blown away by the visuals and the music and the emotional impact of the story. I think it’s a really fun idea to get Isekai-ed into a Shakespearean play as a way to learn about how to improve your marriage. I think the choices made by the player felt impactful, especially towards the end when you realize how it impacts your chances of saving your marriage. I also really enjoyed how you used flashbacks to connect players with scenes in the play, especially since that also helped communicate the values you were trying to impart through gameplay.

If you’d like to continue this for P4, I suggest rewriting some of the marriage scenes to make them feel a little more realistic. For starters, I was uncomfortable with how Sarah hits Vincent with a pan, especially because at the end of the game it’s implied that what she did was fine. I think exploring how both partners contributed to the toxicity of the marriage is important. Whereas Sarah was frustrated by how much Vincent was pulling away, her lashing out really only made things worse—this is the problem with toxic relationships, because over time, one person’s harmful actions/inactions produces further harmful actions in the other. I haven’t played the route of the miscarriage though so I’ll continue experimenting and see how the tone changes with different endings.

Thanks for such a fun game!

Hi Krystal!!

This was SO SO COOL. I can’t believe you did this much in such a short period of time. The polish of the visuals, sound design, and completeness of the story just blew me away. I loved seeing how this has evolved from your figjam flow chart prototype.

Here are some things I really liked:

1. The integrated onboarding of the worldview and mechanics felt smooth. The meaningless choices in the beginning were great at that.

2. I loved the general idea of this project, it’s a cool parallelism you’re drawing

3. I felt very immersed in the worlds. The visuals, sound, dialogues and character designs really drew me in

If you choose to work on this further, here are some things I think you could play around with:

1. It would be nice to get a bit more of a recap on the overall story and characters of Romeo and Juliet from the get go. I like how you are embedding story recap in interactions with characters, I just think there could be a bit more onboarding on the worldview and the rivalry of the two families

2. I think the connection between when a flashback is triggered and a Romeo Juliet scene could be made more clear to really emphasize that parallelism

3. I would make some of the points of conflicts between Sarah and Vincent a bit more specific. I want to know more about their personalities, right now they feel bit generic.

4. I want a more explicit reason for why Vincent is motivated to stop Romeo and Juliet’s relationship from the get go, especially when he was less less emotionally intelligent at the beginning of the game.

Thanks for the game!! It was really fun

For some context, I am heavily involved in the Stanford Shakespeare Company (I was even the president at one point!). Last spring we did Romeo and Juliet, and to me R&J has always been one of those stories where every time I watch it, I desperately wish I could prevent some of minor decisions which have large consequences. Last spring between the rehearsals and the shows, I watched this play probably 10-15 times in the span of a week or two, and I was pleased to find that all of the most aggravating decisions the characters make, were things I could influence. The most consequential decision was killing vs not killing Tybalt, on my first playthrough, I was delighted that I could prevent Romeo from making the tragic mistake. I think that choice was a little hard to parse in terms of execution. I had to keep going back during it to ensure all the right decisions were made during the sequence, I think only one of the early decisions during the fight actually changed the outcome, because a lot of the later choices during the sequence didn’t seem to affect it. That being said, that’s more of a minor mechanical issue than anything else. Getting to spare Tybalt was a really cool feeling, I really liked the alternate universe that arose from this decision. It felt very grounded in the world of the play, and actually felt like what would probably have happened if Shakespeare wrote it that way. I also really liked the choice of us delivering the letter to Romeo, on this path in particular, it felt like there were a ton of different choices that could have led in different directions. I also liked that even when ending the play with the lovers happy, you could still make mistakes in the real world and get a bad ending.