An isolationist shoots themself into space…

Wild Space (playable here) is an interactive fiction video game published on Itch.io, that explores the loneliness of being in space. It was developed in the Unity Engine with help from the Yarnspinner library for dialogue and state-tracking. A brief description of the game:

Life sucks back on Earth. In Wild Space, you’re an astronaut isolated from the rest of the world. You’ve been working in space at a remote station for the past several years, responsible for reporting foreign objects and alien lifeforms back to Earth’s headquarters. Who knows what you might find out there?

Note: This game mentions isolation and depression and includes subtle hints towards abandonment and death of a loved one. If you are sensitive to these topics, play this game at your own risk.

(!!!) SPOILERS AHEAD (!!!) Before moving on, play the game first! You have been warned.

Figure 1: Image of the Wild Space title screen

Game Map

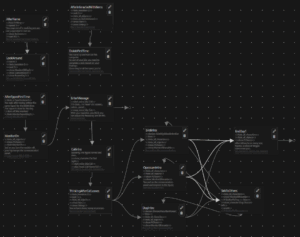

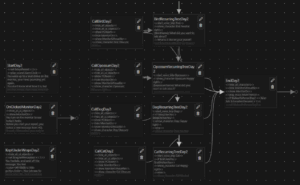

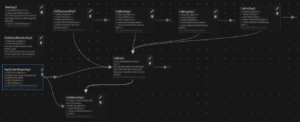

In Wild Space, there are a total of three days and five endings. The ending the player achieves depends on how the player interacts with the environment. View the full map of the game via nodes in the images below:

Figure 2: Full map of Day 1; this day is an introduction to the four characters and decides whether they stay around for Days 2/3

Figure 3: Full map of Day 2; this day is a chance for the player to choose two out of the four characters to further relationships

Figure 4: Full map of Day 3; this day tests the player’s relationship and determines which ending they will achieve

Game Overview

Wild Space is much more than a game exploring isolation; it explores finding community among others that are “different”. It does this explicitly through having the player, who has lost their connection and love for humanity, talk to friendly alien lifeforms that take on the appearance of anthropomorphic animals (“furries”). This game is meant for any audience, but aims to resonate most strongly with an audience who may not engage much with communities that are different. To test this, my playtesting is split between people who identify as “furries” (people who enjoy anthropomorphic animals, or animals with human-like characteristics) and “non-furries” (those who do not identify as a “furry”). More demographic information on playtesters can be found in the History and Revisions section.

The game primarily explores Isolation vs Connection (the player decides whether to remain isolated, or allow the opportunity to develop bonds with strangers), Duty vs Compassion (the player decides whether they follow the instructions of their job (reporting the aliens to Earth), or spend extra effort in protecting their newfound friends), and Identity and Healing (the player learns about every alien through hearing about their unique challenges: desire to make change amongst oppression – Gnarp the Cat, freedom from oppression – Purble the Dog, redemption and expression – Joey the Opossum, and grief and purpose – Alfie the Bird).

Primary Goal

My main goal is to have players place their trust in creatures that they’d never met before. In other words, I wanted to create empathy between the player and characters who they’d have no reason to trust. Luckily, I felt that the premise of the game was already built on a foundation of distrust; why would a human, tasked by Earth to report alien life, have any reason to believe statements being made by unfamiliar life? The game then tests the player on this trust level through various checkpoints where the player chooses to either (1) adhere to their job and report the aliens back to Earth, or (2) lie to Earth and keep silent about the life they encountered. From a majority of the playtesting sessions, I realized that (2) was the more common option, so I consider this largely a success. I attribute this largely to the cuteness of the aliens (as anthropomorphic animal creatures) and boredom induced throughout the game that make the subsequent alien encounters “fun”. Evidence of this can be found in the History and Revisions section.

Figure 5: One of the “cute” characters present in the game: Gnarp the Cat

Use of Medium

To make use of the medium (Unity Engine), I decided to implement more interactivity to differentiate the game from a simple click-through interactive fiction. I did this to (1) create immersion AND (2) emphasize the impact of the player’s choices.

Some additional mechanics present that aimed to have the player actively take on the role of the main character involved typing up reports and clicking on objects throughout the room. Mechanics designed to let the player witness the impact of their actions included a visible representation of alien relationships and a vignette effect representing the player’s self perception value.

Some other quality-of-life mechanics were also implemented, such as the Skip Text toggle and History button.

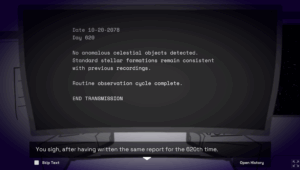

Figure 6: An interactive part of the game where the player can type to slowly build up their report

History and Revisions

The game went through several major revisions. This section will list the important aspects of playtester feedback, as well as the changes made (or not made).

Playtest #1: Krystal, a non-furry designing a “Romeo and Juliet Isekai” game in CS377G

Figure 7: The first playtest with Krystal

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Krystal:

- Expressed annoyance at clicking the text box repetitively. After this, I started heavily considering more interactive forms of examining objects in the environment, rather than always defaulting to the text box.

- It felt like there was too much character interaction, which made Krystal not feel isolated, but overwhelmed. After this, I started to increase the number of moments where the character can personally reflect, to make the distance feel more serious.

- The playtester mentioned they’d react differently in response to waking up on a random spaceship, since there was no initial context. (At this point of the game, the player wasn’t explicitly described as an astronaut in space, but just woke up in a random space station.) I agree with this take, and so I added more options that allow the player to convey their surprise.

- There were issues where obscured characters didn’t disappear after another character had appeared, and some voice blips were too loud.

Playtest #2: Richard, a non-furry who explicitly stated he was “okay with furries”

Figure 8: The second playtest with Richard

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Richard:

- The playtester liked the somber music, felt it really added to the emotion of loneliness in space. He thought the game was immersive, and was surprised at how serious the opening scene was.

- The initial name I choose as the placeholder matters. The playtester found the placeholder name “Dingle” really funny.

- Thought the furry character was silly and laughed when they showed up. However, my game was using low-fidelity assets and I knew this could potentially be circumvented by developing a higher-fidelity “slice” of my game by creating more polished character assets (leaving objects the same, as he didn’t have any strong emotion towards those).

- Found certain choices to be “too much”, since it was mostly clicking through text. After this playtest, I added some other ways to interact with the story, such as a typing-a-journal-entry section and click-on-objects-in-the-scene section. This made the game less of a “clicking through text boxes” simulator and, in my eyes, made the story more engaging.

Playtest #3: Ari, a furry whom I met on the internet

Afterwards, I decided to get another viewpoint on my game — so I resorted to going on the internet to have a furry playtest my game. I did this on Discord rather than in-person, and had him share his screen so I could observe what he was doing. Ari identifies as part of the furry community and spent a total of 8 minutes on gameplay, narrating the lines out loud as he went through the game.

Figure 9: The third playtest with Ari

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Ari:

- He liked the overall vibe and the music of the game. Thematically, I was sure that I was doing well.

- When asked about if he thought the game was linear or branching, he said he believed the game was linear with minor state-change consequences for bad actions, which is not inaccurate.

- The playtester wanted the music to range based on the environment, since the same track would play throughout the whole game. To fix this, I created a crossfade audio manager, to make the track change based on the character present on the screen. This drastically changed the “vibe” of the game depending on the context.

- The playtester wanted to know more about the main character’s context, personality, and resentment of himself. To incorporate this feedback, I added more scenes that appear each day where the MC personally reflects. This helps the player learn more about their own character before jumping into “character dating”.

- I also added a journaling scene (through the “reports”) where the character writes his own thoughts down. Because the MC is in space, I don’t want them to be talking, but rather thinking to themself non-verbally. This added to that aesthetic perfectly.

Playtest #4: Marielle, a non-furry who enjoyed the anthropomorphic animals in the game (recording link here)

Figure 10: The fourth playtest with Marielle

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Marielle:

- The playtester noticed some areas that weren’t explained very well in the dialogue. For example, “Since day one” → should specify what day it is now, and “Recall a fond memory” → be specific what this memory is.

- There seemed to be a lot of meaningless options that the playtester simply did not care about. I removed a few options after this playtest to be less overwhelming (additionally, I felt as if less options made the remaining options feel more impactful and different from each other).

- “Why do they look like kpop ideals LOOK like seriously”

- The playtester felt the transition between floating in space and being on the spaceship at the beginning was abrupt. Because the game immediately cut between the two scenes, I added a transition fade between these areas and fleshed out more about the player’s context through the dialogue.

- “Sometimes they wink at you, sometimes they gave you love hearts. I loved that”

Playtest #5: Altair, a furry with expertise in astrophysics and planetary science

Altair is a student at UC Berkeley who was over for a weekend, and offered to help playtest. He does identify as a furry, so it was interesting to see his live in-person reaction while playing the game. Given his focus as an astrophysics major, he gave some good comments on the overall theming of the game. He also told me that space didn’t have an atmosphere so I had to rewrite a lot of the “formal reports” throughout the game.

Figure 11: The fifth playtest with Altair

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Altair:

- He told me that space has no atmosphere… so I fixed a few inaccuracies throughout the dialogue.

- Mentioned that an initial dialogue box said that the protagonist was scared others would think they were crazy for seeing aliens… but this is ironic because the protagonist’s job is to look for aliens

- Overall, felt the story was on a linear track to drive a plot point, except when choosing one of the three to talk to. In this version of the game, there was not yet anything tracking the relationship between the player and the characters. This indicated to me that the game needs more visible state.

- Claimed he was initially curious when seeing the furry characters, and then felt happier as he warmed up to him.

- Complained that the hitbox for the dialogue arrow was too small; I made this larger.

Playtest #6: Ari, a furry whom I met on the internet (repeat playtester)

Figure 12: The sixth playtest with Ari

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Ari:

- Similarly to Altair, he wanted somewhere to look for live state changes so he could tell if his changes actually mattered.

- Thought that the hearts that showed up on top of the characters when certain actions were made were confusing. I ended up not changing this, because other playtesters had expressed positive sentiments with the little heart pop-ups.

- Thought the type-to-interact section was neat, but was a little unclear when he started typing and other words started showing up.

- Wanted a background to be added to the game, since this version of the game only had a gray background. I added a space background not too long afterwards.

- Thought that the Day 1 dialogue was much better than the Day 2 dialogue. After this, I spent more time fleshing out Days 2 & 3, since I had initially focused on making a good Day 1 experience.

Playtest #7: Ngoc, a non-furry designing an “Anti-AI Art” game in CS377G

Figure 13: The seventh playtest with Ngoc

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Ngoc:

- Struggled with figuring out what objects were interactable at the beginning of the game. To fix this, I added a color tint to highlight clickable objects.

- Noticed a bug where Joey (the Opossum) didn’t introduce himself, but still showed up as “Joey” as opposed to ???. I fixed this by making the algorithm consistent with the other characters.

- Was unaware of any state tracking the player’s self-perception. To further emphasize the player’s depression and how it varies throughout the game, I messed around with vignette colors around the sides of the screen.

Playtest #8: Christina, the professor of CS377G

Figure 14: The eighth playtest with Christina

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Christina:

- She took the game pretty un-seriously after naming herself “billy bob joe”. I noticed that some playtesters would simply not respect the vibe of the game being serious. I thought initially about forcing the player to embody the main character by removing this “input name” section. Eventually, I decided against this because I wanted to create more of a personal connection to the person playing, and based on what I heard by other playtesters, dating simulators typically benefit from more player agency.

Playtest #9: Madison, a non-furry who enjoyed the hidden dating simulator aspect of the game (recording link here)

Figure 15: The ninth playtest with Madison

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Madison:

- Suggested putting quotes around text when a character was talking. However, I believed there was already enough of a difference between narrator text (with the name “Narrator:”) and character text (where the character name would appear), so I did not do this.

- At the beginning of the game before the characters appeared, and while she was typing the reports back-to-back, she expressed: “I’m so bored” and “Again… so monotonous” (after the second report)

- Was surprised about the politeness of the alien:

- “Oh my gosh, is this a compassionate alien?”

- “I do like cats, and this alien looks like a cat”

- I want to be nice … chooses “Who are you?” for Gnarp

- “Aww, I made a friend! Even if I was a little mean at the end”

- Wondered: “What is the sad backstory of the narrator”? I realized at this point, I had not fleshed out the narrator’s backstory in terms of specifics. I started rewriting some portions of the game to include more background on the main character’s friends and family afterwards.

- “Oh, I have two hearts! It’s like an alien harem”

- When this playtester played, certain actions would be pre-pended with parenthesized text that indicated a prerequisite that had to be met before the action would be selectable. She thought it was confusing, so I removed this parenthesized text; this meant that players who were playing more positively would simply not see the extremely negative responses. I was fine with this outcome.

- I did not supply any context for the game, and so commented: “Is this an alien dating simulator?”

Playtest #10: Sebastian, a non-furry who expressed interests that were similar in artistic nature to the furry fandom (recording link here)

Figure 16: The tenth playtest with Sebastian

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Sebastian:

- Questioned whether the “Narrator:” title text was necessary for internal monologues; this made it seem like someone was speaking for the player, rather than the player themselves thinking. I ended up removing this.

- Liked the green text signaling perception going up/down, even though this only appeared at the beginning. This was a sign that I could do this in every place where perception went up/down.

- Initially thought there was a dark figure in the room, rather than on the monitor. I added an additional asset where the monitor had a silhouette to make this more obvious.

- Noted that there was an unanswered question in the plot: “why all the aliens now?” I ended up explaining this narratively by having the player bump into the machine, and tapping into an unknown signal.

- After talking to two aliens and realizing that some stayed if they had high-enough heart scores, commented: “I now understand my goal”

- “I feel like I have to report them, but they’re gonna kill my friends” (referring to Earth)

Playtest #11: Jess, a non-furry (recording link here)

Figure 17: The eleventh playtest with Jess

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Jess:

- Clicked on dialogue box rather than arrow to advance. To fix this, I made it so the entire dialogue box had a hitbox instead of just the tiny dialogue arrow.

- Initially tried to press the Enter button to confirm the name entry. I made this work afterwards.

- “OH?? Is this a potential love interest”

- “Wow, what is this harem!” (after seeing three characters)

- “You know what, I didn’t like humans anyways”

- Felt like it was too easy to get the hearts: “I feel like I should’ve gotten extra points for that” – referring to “You’re cute”. I made gaining relationship points a little more sparse afterwards.

- Wanted to know when they were “losing” at the relationship. I balanced the animations for when the player earned relationship points by adding an animation when the player lost relationship points.

- “I’m being rizzed up so hard right now from Gnarp”

- “I don’t want to talk to anyone else” (progressed to Day 3)

Playtest #12: Alexander, a non-furry

Figure 18: The twelfth playtest with Alexander

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Alexander:

- Spammed into the name input box (trolling). I added a short character limit to circumvent super-unserious names.

- Found it frustrating that the history button would disappear with the dialogue boxes, especially in points where he had to type on the monitor and couldn’t view the messages that preceded it. I made the history button ALWAYS shown.

- Found a bug with Alfie’s branch, where the ending was not obtainable. I fixed this.

Playtest #13: Kevin, a non-furry

Figure 19: The thirteenth playtest with Kevin

Some noticings and changes after playtesting with Kevin:

- Found a lot of the dialogue kind of strange and unnatural throughout the game. I made a lot of dialogue tweaks after this playtester’s feedback.

Final Reflection

Overall, developing Wild Space taught me a lot about the struggle that interactive fiction writers go through. It was very difficult to get the dialogue to a point where I felt that it wasn’t “too cringy”, and I spent a lot of time fleshing out the character backstories (even for minute details that aren’t present in the game at all). It was also a great experience for me to start learning how to use the Yarnspinner library; in hindsight, I’m glad that I went this route as opposed to developing my own dialogue system. It became very apparent that managing state was integral to making the game interesting, and once it become necessary to track variables for each of the interactable characters plus the main character, I was super happy to have had a dynamic-enough system that supported my plans.

If I decided to make another interactive fiction game in the future, I would 100% spend more time thinking about my characters’ backstories before starting to write the dialogue. I didn’t realize how important context was in a game as narrative as this, but even something as simple as the main character’s backstory shaped the mechanics and overall direction of the game. I started Wild Space as a project to see if people would open up to anthropomorphic animal characters, but as it evolved (largely through playtester feedback), I soon found myself designing a social experiment. Would you rather adhere to the rules of a society that doesn’t acknowledge you, or potentially find joy in joining an “othered” community?

Hey Lucas! Really cool game you made here. The UI is phenomenal — I can’t believe you put this whole thing together in just a couple weeks. Also, the hand-drawn art is really cool! It immersed me in the story and the overall pacing and delivery of the content felt like a fully fledged game. Overall, I really don’t have many recommendations for you except maybe an option to have a “faster text” option that quickens the pace text is written / skips the typing animation of text, but doesn’t skip through all of the text before decisions. Keep up the really good work!