Reading

Game Response

For this read and play, I played three games: Adventures with Anxiety! (35 minutes, finished), We Become What We Behold (~5 minutes, finished), Depression Quest (~15 minutes, not finished). Since I didn’t finish Depression Quest, I won’t spend too much time discussing it outside of a short reflection at the end.

Adventures with Anxiety!

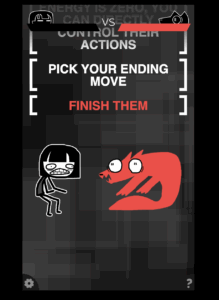

Adventures with Anxiety! (link) is a game by Nicky Case targeting anyone who experiences anxiety—and even potentially people who have loved ones who experience anxiety (so most people). It is a visual novel on an HTML5 platform. You play as the “anxiety wolf” of a person who is navigating their experience with anxiety in college. Scenes are set up like “fight scenes” in combat games where you get points for “warning” your human about potential dangers and “protecting” them from harm.

Screenshot: example of the fight scene mechanic

The game opens with your human eating a sandwich alone when they get a text inviting them to a party. Your first “combat” occurs, before the chapter ends with your human deciding to attend the party. The next chapter is your human at the party, where your next fight occurs. This is followed by another party chapter where your human gets drunk, then by a closing scene where your human is again eating a sandwich, but this time you don’t fight and instead work through your concerns as a team. I played the game all the way through, which took about 35 minutes.

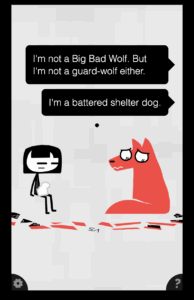

Screenshot: The game mixes serious topics with comedic responses

This game is a narrative visual novel that touches on topics of mental health in a comedic way. The comedic aspect helps to keep the user engaged while attempting to reframe their perspective on anxiety—whether to help them work through their own (the game is captioned “Whoever you are, stay strong & good luck!”) or understand what others may be experiencing. At first, I wasn’t convinced that the comedic format allowed for a serious discussion about the impacts of anxiety, but by the third chapter when the tone shifted to more serious, I appreciated the impact that this scene had in comparison to the tone of the rest of the piece. Reflecting, I feel as though adding in comedy allowed the game to still be fun in a more-traditional, less-crushingly-emotionally-heavy way that expands its audience beyond the more serious group that probably overlaps with games like Depression Quest.

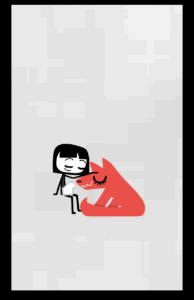

Screenshot: The shift in tone at the end of the game

It was interesting doing this week’s reading after playing this game because it made me reflect on the possibility space that the game created, even within such a restricted narrative. The choices you make as a player don’t have much (any?) impact on the outcome of the story, but the emotional reaction and your own interpretation of the takeaways of the game can vary greatly based on how you view the social systems described in the game through the lens of your own experiences. I think that this game was also very on-the-nose in terms of describing what social phenomena it was attempting to model, clearly showing how “play” here relates to a deeper understanding of the systems that make up mental health challenges (anxiety).

Adventures with Anxiety! is very different from my game, Chronos. They are in different formats (mine doesn’t have any illustrations) and have extremely different tones (mine doesn’t contain any humor). However, I enjoyed the way that the game, which felt very on-the-nose at the beginning, forced me into deeper introspection about how I might be able to reframe my relationship with my own mental health struggles. I feel as though I can transplant this into a similar goal in my game of getting players to reframe how they interact with historical material and give back their agency to understand biases. Switching tone at key points is a tool that was used in this game for its purpose that I could possibly use similarly in my own.

The game attempted to convey that mental health challenges are a journey, and that you can’t make progress toward living in a healthy way despite them if you hold stigmas against yourself. You need to give yourself the space to understand your emotions before you can begin to work through them, as frustrating as they still might be. This message was largely conveyed through the last scene, but it was also conveyed throughout by forcing you to play as the anxiety. This generated empathy for the anxious parts of character by personifying them as a “guard dog” that is just trying to help.

Screenshot: Empathy for yourself

At first, I wasn’t a fan of the “fight” scenes and the personification of anxiety. However, as the game moved on I appreciated the storyline more, and I do feel like the message was successful by the end. The game made me reflect on my own frustrations with my anxiety and how I might reframe them with more empathy for myself.

We Become What We Behold

We Become What We Behold is a visual game also by Nicky Case! The game works by showing a bunch of stick figure characters wandering around an empty screen. There is a TV in the middle of the screen showing fake news broadcasts. Your mechanic as a player is a box that you can move around and click. Everything within the box is captured as a picture, and if something interesting is happening, it becomes a broadcast.

Screenshot: Example of a broadcast

The game focuses on cycles and how giving your attention to something feeds it. The game ends with the people on the screen killing each other (squares and circles) in widespread violence that is originally instigated by someone yelling at another figure and the reporting calling it a hate crime.

Screenshot: A violent ending to the game

I thought that the game was effective at using simple dynamics to model a complex phenomenon. There are many ways you could read into the gameplay, but I appreciated the use of a simple point-and-click mechanism to make the player aware of how their attention is drawn to particular actions. I also found it interesting that you couldn’t stop the chain of events by focusing on the positive (at least I don’t think you could). This felt more accurate in terms of media attention rather than personal attention.

Screenshot: attention to positive actions did no good

I want to take note of the use of simple mechanics to engage the player in the game. I’m worried about finding a balance between a UI that engages the player and one that is too complicated and takes away from the narration. This is an example of a very simple and effective UI that I can take notes from to simplify (or just even out) my own.

Depression Quest

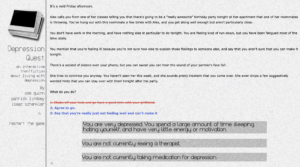

Since I didn’t finish this game, I will talk about it in relation to Adventures with Anxiety! Depression Quest is a game by Zoe Quinn, Patrick Lindsey, and Isaac Schankler that attempts to show the player an accurate portrayal of experiencing depression. It has long narration with lots of details about your personal life and internal state.

Screenshot: An example of long-form narration in Depression Quest

Playing the first few scenes of this, I spent a lot of time contrasting it with Adventures with Anxiety! because it touched on a similar topic in a very different way. This game has a much more serious tone, and I wouldn’t be surprised if there is less of a “happy ending” than Adventures with Anxiety has. I felt more immersed in the world in this story, but it was also a much heavier story. In my own story, I want to find a balance between the immersive aspect of this story and the lightheartedness, with undertones of serious societal critics, seen in Adventures with Anxiety.