For this project, I played Emily is Away (link here), a branching fiction game where you play as a student chatting with their high school friend Emily online. It is designed for a slightly older audience (above young adult), since it frames itself as nostalgic for a time before platforms like Skype or Facebook. Created by Kyle Seeley and playable on Steam, the game starts with your senior year of high school, directly before an end-of-year party. You are chatting with someone named Emily online, and the prompts soon tip you off that you are interested in this person

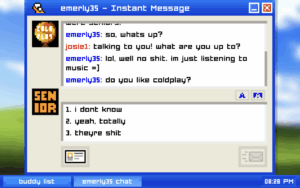

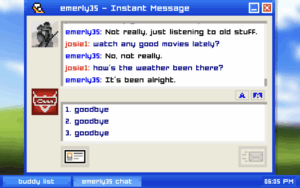

Description: An example of a chat with Emily and the types of dialogue options you get as a player.

You obviously have a shared interest in music, and Emily is very chatty in this first conversation. The first chapter ends when Emily leaves for a party, which you can also choose to attend. I did so in both of my playthroughs.

The game then continues through five additional chapters, each one about a year apart and consisting of a single conversation with Emily, which ends when she leaves the chat (except in the last chat, where I was the one to leave both times). You hear about her relationship situations and have the opportunity to meet up with her at one point. Since each chapter is a year apart, you have to pick up cues about events that have occurred in the meantime through context in the conversations. I played the game through in its entirety twice (~30 minutes per play through), and got similar outcomes both times.

The Four E’s

Evocative: The game had a very nostalgic feel, with even the game description starting with the question: “Remember a time before Facebook and Skype?”. This helped to tie it back to memories of the past—at least for those of us old enough to remember messaging platforms. It made me think about texting friends and crushes in high school, and how emotional virtual conversations could feel when you were less able to control when and where you could see your friends. You were limited in your choice of responses (with some prompts even misleading you as to what would actually be typed when you chose it), but still given the opportunity to invest yourself in your character by trying to build a specific type of relationship with Emily, which was very evocative of real life.

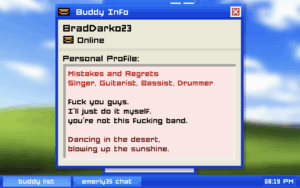

Enacting: Throughout the game, you are able to interact with the interface by choosing messages to send to Emily and by reading the Personal Profiles of other characters (which I didn’t discover until the second play through). I would be curious to see whether how long you take to respond to each message has any impact on the gameplay; however, the only mechanic for impactful interaction that I discovered was the ability to choose between message options to send to Emily.

Description: A sample profile of one of the characters in the game

Subgenre

Emily is Away is a Visual Novel, which limits the choice that you get as a player. From reading the comments of other users online it seems like there is never a happy ending—so every time you’re faced with options you wouldn’t choose in real life, you’re forced to sit there and reconcile that the story is going to end in sadness, and there is very little you can do about it. I think that this was a good medium for this game because there already exists the aspect of frustration over not being able to control another person’s responses to even your most well intentioned actions, and the component of not always being able to control your own actions compounded this frustration. Also, it seems as though there is a set genre of ending for the game (sad, frustrating, etc.), which might be difficult to achieve in some of the more freeform genres.

Inspiration and Criticism

One aspect of the game that I found interesting was that, while I would say you gain empathy for the plight of your character, you don’t get to build much of a narrative for yourself. The story is mostly focused on Emily and the snippets that you learn about her life—responses to anything you share are typically relatively short, and Emily never pries into your life, so we don’t get to learn much about ourselves. This might be intentional to allow you to project more of yourself onto the playable character, but since I didn’t feel as though my personality was particularly well represented in the prompt options and I wasn’t given much information about my own character, I ended up having to imagine their personality on my own.

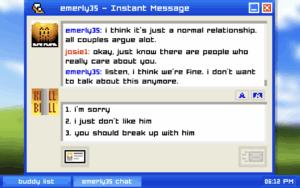

Description: An example of a place where I would have picked a different response in real life—why not continue to talk about it without alienating Emily by passing judgement?

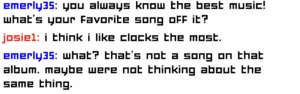

Description: Example of acting on incomplete information about your character

This isn’t innately a bad thing, but it is something to make a decision about as the game designer. I did enjoy the emotional impact of the game and its ability to generate a feeling of hopelessness and frustration—getting the player to root for a relationship with such few details is impressive! It shows the emotional impact that the environment can have without overexplaining or too much guidance by the designer.

I also enjoyed the increasing emphasis on lack of control as the game went on, reiterating one of the main messages of the narrative. This culminated in the lack of choice at the end, where even if you chose to ask a personal question the game would backspace and delete it, and eventually all choices were removed.

Description: Loss of choice at the end of the game

Final musings

The game attempted to draw empathy primarily towards the playable character, with some moments pulling empathy towards Emily as well. Allowing you to invest yourself in the narrative and participate in the conversations helped you to empathize with the character, and the emotional impact of Emily’s responses also contributed to your ability to immerse yourself in—and thus empathize with—the character. I did feel empathy towards the playable character, along with frustration towards the limited choices that the character had. The limited range of personalities that you are able to take on was somewhat of a limitation in the extent to which players with different personalities might empathize with the character. For me, the game evoked frustration and the nostalgia of learning about relationships and dating norms for the first time in high school. The character felt a bit naive, which again added to the nostalgia and the desire as a player to take care of the character you are playing. I didn’t feel like either Emily or my own character was “in the right” throughout the narrative, which helped to generate more complex emotions.