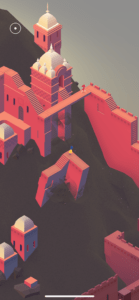

This week for my critical play, I chose to play Monument Valley 2, a mobile game developed by ustwo games, and available on iOS and Android. I would describe the game’s target player as a casual mobile game player that enjoys narrative puzzles and beautiful art. After reading the excerpts from Shira Chess’s Play Like a Feminist that urged us to reconsider how we engage with games from a feminist lens, I saw Monument Valley 2 as more than just a game of illusion-based puzzles and aesthetic art.

Thesis:

Playing Monument Valley 2 as a feminist means recognizing that intergenerational emotional labor sits at the core of the game, along with themes of strength in motherhood and care. While the game does excel in the more subtle rejections of masculine-coded games and themes, I believe that the game falls short in intersectional representation that is an important aspect of feminism.

Analysis:

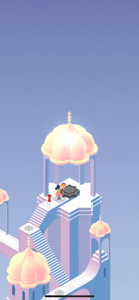

When I played the first level, I was just moving a character (Ro) and manipulating the monument to solve puzzles. But from Level 2 and onwards, the gameplay, theme, and emotional investment I had in the game shifted. I was no longer just playing as a character to solve puzzles in a monument, I was playing as a mother who was teaching her daughter how to navigate the world that they found themselves in. Clicking on the screen to move my character Ro, I watched the gameplay unfold as Ro would move and her daughter would follow closely behind her mother’s every movement. But then at the end of Level 2, I watched as Ro and her daughter climbed symmetrical towers, mirroring each other, still connected but on different paths, almost like a metaphor for growth in motherhood and life in general.

It was clear how tender and mutual Ro and her child’s love for each other was. Their tender hugs throughout each level and the way in which Ro would occasionally look back at her daughter as they were moving in tandem, while solving puzzles together, solidified the feminist theme of care as a form of strength.

In one level, I moved Ro’s character down a path, expecting her child to follow her as normal, but as soon as Ro made it to the platform it ripped away and separated her from her child. I was surprised how emotionally invested I was in their relationship, just being a few levels into the game. When the two were finally reunited and fell into each other’s embrace, I myself s the player felt a release. The game’s intentional decision to use just a hug—no sound effects, no dialogue, no cutscenes or game rewards for reuniting them—did more to affirm the immense emotional labor than many other louder and busier games could ever accomplish. Moments like these also echo Chess’s concept of feminist play not about dominating entire systems, but repairing them — these levels are cyclical in its emotional arc (mother and daughter always are reunited at the end, even if they are separated in the middle), mirroring the idea that motherhood is an ongoing process and although the mother-daughter relationship may be strained at moments, the entire process itself is beautiful and rewarding.

In the reading, Chess talks about how feminist games can positively affirm identity and familiar roles. In mainstream games (and games that I’ve played throughout this course), the themes of motherhood and domesticity are traditionally dismissed, let alone affirmed and celebrated. Monument Valley highlights these identities at the forefront of its game, not just as a superficial decoration. The mother and daughter relationship, across generations, is the core narrative. Ro received wisdom and care from a mystical, feminine, mother-like power as well, and this is a motif that is returned to at the end of every level. Reading quotes like “Even in youth we knew the work our mothers left for us” instilled in me the power of legacy that mothers can create and pass down.

It is clear that Monument Valley was effective in reinforcing and positively affirming the themes of motherhood, femininity, and care. However, I believe that the game could have been a great medium for more intersectional feminist storytelling. As Chess described, feminist games not only wrestle with gender, but also with race, class, and sexuality. The game presented motherhood as a very mystical and universal experience, but stopped short of telling a more specific and intersectional story. While I understand that the use of faceless and voiceless characters was an intentional design choice that did add to the aesthetics and mystique of the game, it also diminishes and flattens much of the experiences of motherhood.

Lastly, the game mechanics also helped to subtly reinforce these feminist identities and roles. The puzzle-based game uses rotating bridges, illusions and visual perception, wheels, and motion-plates to power its puzzles. There is no aggression, no enemies, no urgency. In fact, it is quite the opposite—mother and daughter work together, often needing to stand on motion activated plates for one another to move around, sometimes having to go through the same path multiple times so that the other can solve its puzzle, before the two can be reunited. There are multiple sources of feminist agency in this game that make for a powerful and beautiful narrative, especially when you play it like a feminist.