In the very first ‘page’ of the game, they very explicitly explain that this game isn’t one in the traditional sense meant to be “fun or lighthearted,” suggesting against someone playing it if it may be triggering. They add on to explain that they want to illustrate to people without depression what it’s like to live with and also to simulate it to potentially show to those with it that they aren’t alone, which is also why I think they made this game super accessible (online) and free to play. I think this idea is well supported by the (non) being in parentheses in “(non)fiction” in their tagline as even though this story is assumably not actually representative of anyone’s life, but very easily could be. They want to be realistic without putting anyone’s personal story out there. Our character’s story is intentionally ambiguous to show the ways in which depression can affect anyone at anytime and to show how sometimes, the “obvious” decisions aren’t as obvious or easy as they seem.

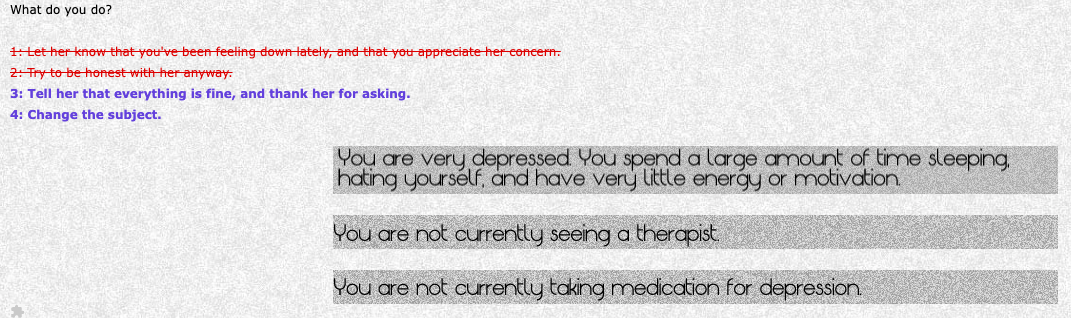

As for the game itself, it operated similar to a “Choose your own adventure” game, but with an interesting mechanic: sometimes, some of the options would be restricted/limited.

I am only able to select the blue options, even though options 1/2 are the “right” ones.

Sometimes, the option that I was interested in taking (which very commonly was the option that would probably be “best,” which, of course, is a subjective term), was limited. It would also commonly be the decision that I would suspect someone with depression would struggle to make — like telling someone that I (the protagonist) am not feeling good today or agreeing to go out with my girlfriend. I think this creates the dynamic of a sense of paralysis that someone with depression might have — to know that they could do something (again, especially when deep down they know it would be better for them), but not being able to make the decision. I think this ultimately leads to mainly the narrative aesthetic, as we are building out the story with every decision we make, but I also think there are aspects of the challenge aesthetic too. This may just be how I played the game, but even though there wasn’t a sought out/described goal in mind, I felt like I needed to help the protagonist overcome their depression — trying to make good, healthy decisions. I was able to get to a “good” ending, so then I tried going through making the worst decisions possible, and then got a “bad” ending.

All the endings are similar in that we conclude with our family at a dinner table but respond differently to our mother.

I think it was particularly interesting that they keep the phrasing of “You are a mid-twenties human being” — our gender and sexuality is kept ambiguous. We know that we love our girlfriend Alex (which in it of itself is a gender-neutral name, which could be intentional), but that really is all. I think this is done intentionally though, just to further show the idea that really anyone can have depression. It doesn’t only happen to people in the LGBTQ+ community. I think this is wise for the sake of being inclusive, but I think it at times made it a little harder to understand the protagonist’s story/background.

As someone who has not had depression (not now nor in the past), I was curious what other players had to say, and I encountered a megathread on Reddit of players upon looking more into the game, and only then recalled that Zoe Quinn was the victim of Gamergate. As I went through some of the reviews in the megathread/around the internet, I think it was clear that some individuals genuinely had problems with the game (namely its inconsistency at times, poor spelling, etc.), but there was also a demographic who clearly were against Quinn and wanted to attack them and anything they were associated with.

Ultimately, Depression Quest demonstrates a complex relationship between game and creator. While the game uses intentional vagueness to let the player create their own story (while limiting them from making “correct” decisions), the harassment surrounding Quinn’s story reveals how nothing is created in a vacuum. The context surrounding a game and the creator’s vision work hand in hand to deliver meaning.