For this week’s critical play, I chose to play Brawl Stars, which is a game that my friends have been raving about but I never actually tried. Brawl Stars is a mobile game developed by Supercell. The target players are casual mobile players drawn to competitive action/combat fast-paced gameplay, and especially those that like to join game rooms with their friends. The game is available on iOS and Android and is a great example of a live service game, ebcuse it is continually updated, endlessly monetized, and incorporates many design elements to keep players coming back (and often spending more money).

Brawl Stars engages players through a combination of mechanical skill, team strategy, and constant game and character progression. But similar to games like Fortnite which we looked at in section, underlying the colorful aesthetics and gameplay mechanics is a structure that is designed to influence player behavior through randomness, scarcity, and time-gating.

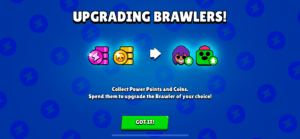

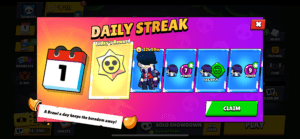

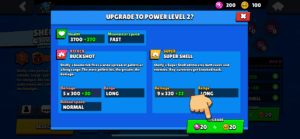

From the moment that I logged into the game, I was flooded with various stimuli. I saw daily streaks, rotating offers, blinking reward icons, and lots of power-up opportunities. When I went through the onboarding process, it was clear that the game embodies the value of progression: collect power points, upgrade your Brawler characters, unlock new game modes.

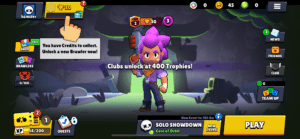

Throughout my gameplay, I experienced so many pop ups randomly throughout that would give me rewards for just staying on the app. These variable rewards are a hallmark design that reinforces addictive behavior—it gets users thinking that if they stay on the app for longer then they will be more likely to get the random rewards.

Moreover, the game implements many mechanics to incentivize users to check the game daily. For example, daily free rewards, random loot crates, and limited-time rewards and events kept me scrolling through the options and kept me on the game when I was about to log off. Some rewards such as unlocked new Brawlers through credit drops are also randomized, which further incentivizes users to constantly check the game.

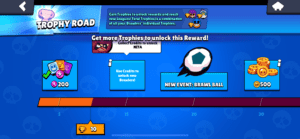

Brawl Stars effectively pairs randomness with near-miss effects and forced choice, as explained in our reading Addiction by Design. The thrill of being so cllose to getting your favorite Brawler from a reward box activates the same dopamine loops as slot machines. And as Edwin Evans-Thirlwell notes in his “living dead” critique of live service games, players are not offered closure or resolution, but rather an endless path of upgrades that never culminates in true completion. For example, you are told that you can unlock clubs once you have 400 trophies — what are clubs? I don’t know, but they sounded exclusive and I felt the desire to join one. Again, we see this idea in motion of constant need for more in the game to feel fulfilled momentarily, but never satisfied because there’s always something more to have.

Now to consider the monetization pressures in Brawl Stars we can look to the storefront. Players can buy power points, coins, credits, and entire characters using real money. Unlike Fortnite that uses V-bucks to obscure the real value of certain characters, Brawl Stars uses information asymmetry: players are only shown the base price of the character, not all of the other fees that come from wanting to max out a character (e.g. costs that come with upgrading characters). And, they are never rold the real odds of getting specific items from crates (instead of buying them).

Furthermore, starter packs and Brawl Passes are designed to seem like good deals for players in the long run, but can actually impose the sunk-cost fallacy. Since players have already bought these packages, they’re more likely to play to make sure they extract the full value of the deal. This system which appears to enhance player agency is actually a calculated move that is engineered to boost player retention. As Designing Chance reading describes, live service games such as Brawl Stars exploit temporal scarcity (e.g. limited-time offers) and the illusion of progression to keep players fixated on potential future rewards.

Brawl Stars is a “zombie” live service game—it is free to play, obsessed with progression, and also devoid of a finite arc. The idea of progress is just an illusion which lures and traps players who feel fulfilled just enough to keep playing, but never fully satisfied.

In terms of the ethics of addiction by design, I believe that it is only ethically permissible to use chance and randomness in games when it adds surprise and fun, but not when it is used to manipulate player spending behavior and encourage an unhealthy obsessio with the game. Brawl Stars, like other live service games like Fornite, targets a younger audience which might not be as aware of the design mechanics at play in the game that are fostering an obsession with the game. Therefore, I’d argue that the use of addictive design is even less permissible for games designed for a younger player audience. However, I will say that although Brawl Stars offers some more monetary transparency than Fortnite, it still uses that distilled feedback loop integral to addictive design. While Brawl Stars is no doubt good at what they due, as shown by players’ long term engagement and their profit, its targeting of younger players should definitely be reconsidered from an ethical lens by game developers.

Overall, I see the hype of Brawl Stars and it reminded me of the game Soul Knight which I was completely obsessed with during middle school. The game is fun, but The game is fun, but now viewing it in a different light, I think that as future game designers, we must ask not just whether our games are engaging, but whether they are fair and transparent.