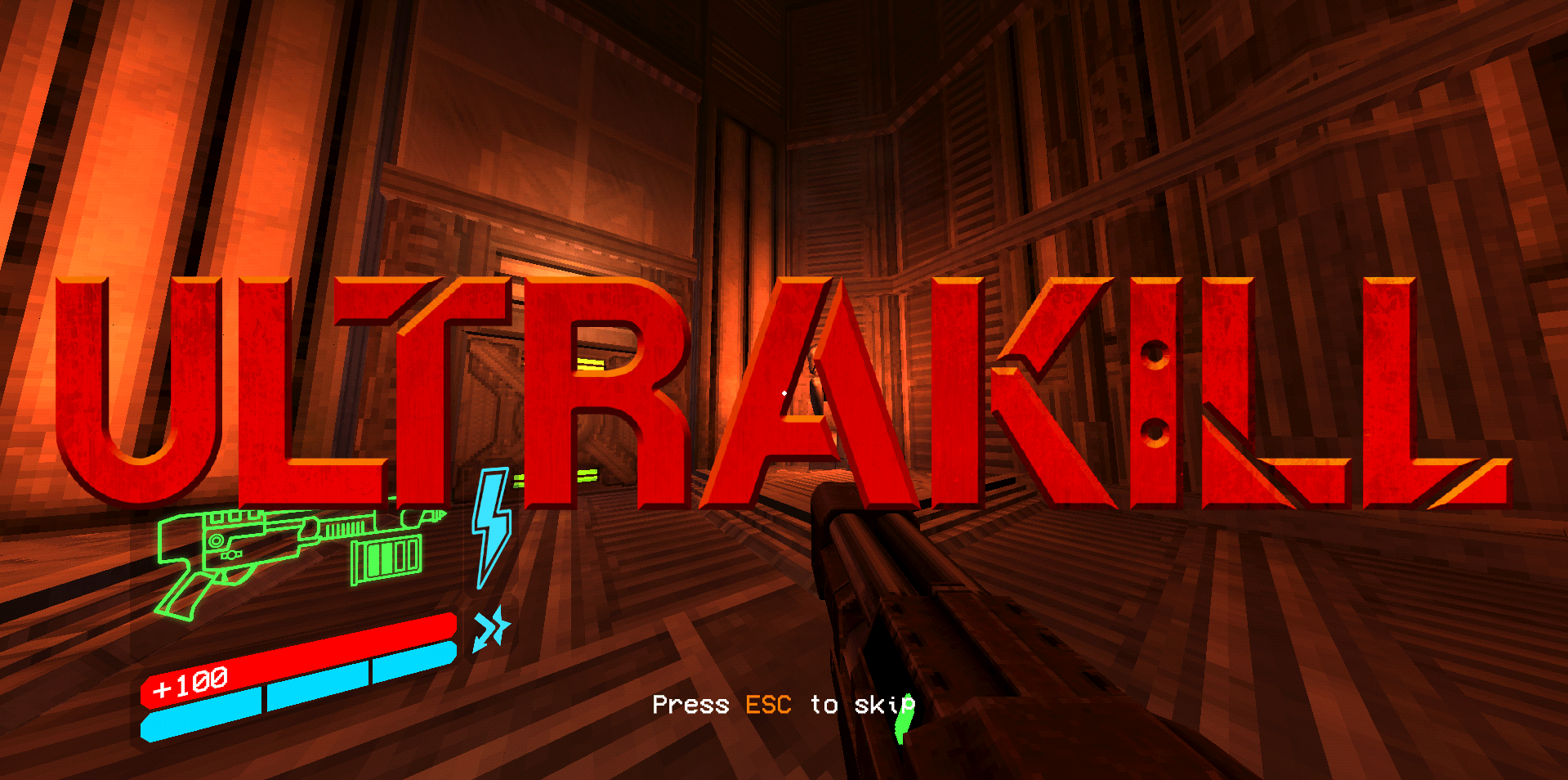

Ultrakill is a video game created by Arsi Patala, also known as Hakita. It is available on Windows PCs, and is still in early access. As of May 2025, the last two “layers” of the game’s planned 7 layers have not yet been released, though the developer has continued to refine and update the first 7 layers in the meantime. Ultrakill is meant for a somewhat more mature audience of adults and teens, due to the amount of violence in the game. While it shares first-person-shooter elements (like the use of realistic guns) with a game like Fortnite, which is open to a wider age range of gamers, Ultrakill’s execution of its killing mechanic is much gorier. Kills, in Fortnite, are sanitized of its more explicit elements—players disappear in a flash of holographic blue when they die, leaving behind their inventory—which allows the violence of the act to feel more abstracted and gamified.  Ultrakill, in contrast, is really bloody. Almost all forms of damage you deal will cause red blood effects to explode out of an enemy, enemies show visible decay when they get low on health, and collapse in grotesque heaps of dismembered limbs when they die. The goriness of Ultrakill’s visuals seem to surpass the realm of realistic to, well, overkill, but it’s still too intense to recommend broadly to children and preteens. Subtler narrative aspects of the game also reference topics such as war, war crimes, religion and the concept of Hell, and the extinction of humanity, which can dip into areas that are also too mature for a younger audience.

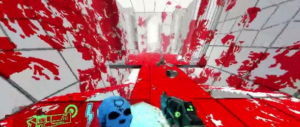

Ultrakill, in contrast, is really bloody. Almost all forms of damage you deal will cause red blood effects to explode out of an enemy, enemies show visible decay when they get low on health, and collapse in grotesque heaps of dismembered limbs when they die. The goriness of Ultrakill’s visuals seem to surpass the realm of realistic to, well, overkill, but it’s still too intense to recommend broadly to children and preteens. Subtler narrative aspects of the game also reference topics such as war, war crimes, religion and the concept of Hell, and the extinction of humanity, which can dip into areas that are also too mature for a younger audience.

In Ultrakill, you play as a robot known as V1, who descends into actual Hell in order to acquire more of its fuel source, fresh blood. Ultrakill’s most basic narrative is one of V1 killing anything in Hell with some blood to offer, tearing a path through differently-themed layers inspired by the nine circles of Hell in Dante’s Inferno. Ultrakill’s mechanics and goals sets the player in opposition to the world around them, but uses its main directive and sidequests to encourage the player to explore and invest themselves in the lore of its world.

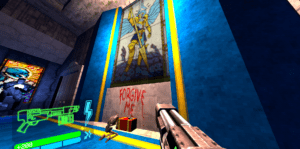

The architecture of its settings is one way that Ultrakill invites the player into its world. Buildings and other environments in the game not only support the gameplay by giving the player extra challenge to navigate as they play through each level, but also provides an informative visual experience that subtly advances the game’s embedded narrative, which involves finding out the details of what happened in the history of the world up to now. While engaging with the challenge aspect of the game by seeking out more creatures to kill or trying to fulfill each level’s bonus missions, players are encouraged to further explore and interact with the environment’s design, and what it might reveal about the world.

By basing its premise around exploring the circles of Hell, Ultrakill already sets up an expectation within players that keeps them interested in seeing what the world has to offer. As I played through the layers, I found myself curious to see what kind of take on each circle’s theme the game would go with. This interest encourages people to be more alert to the aesthetics of Ultrakill’s world, and rewards people with moments of recognition and connection.

By basing its premise around exploring the circles of Hell, Ultrakill already sets up an expectation within players that keeps them interested in seeing what the world has to offer. As I played through the layers, I found myself curious to see what kind of take on each circle’s theme the game would go with. This interest encourages people to be more alert to the aesthetics of Ultrakill’s world, and rewards people with moments of recognition and connection.  It takes advantage of allusion and cliche quite heavily to communicate its worldbuilding, with little details that further reference Inferno—like the inscription on the gates of Hell—and elements that draw from other cultural touchstones. The Cerberi, for example, who guard the aforementioned gates, are named after the Greek Underworld guardian Cerberus. Other layers play on structures and aesthetics that feel familiar or cliched. The Lust layer uses a metropolitan backdrop and magenta color lighting to evoke the idea of a populated cyberpunk city, while also suggesting a sensual and hedonistic feeling.

It takes advantage of allusion and cliche quite heavily to communicate its worldbuilding, with little details that further reference Inferno—like the inscription on the gates of Hell—and elements that draw from other cultural touchstones. The Cerberi, for example, who guard the aforementioned gates, are named after the Greek Underworld guardian Cerberus. Other layers play on structures and aesthetics that feel familiar or cliched. The Lust layer uses a metropolitan backdrop and magenta color lighting to evoke the idea of a populated cyberpunk city, while also suggesting a sensual and hedonistic feeling.

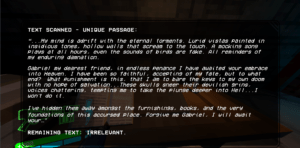

There is a level of detail in the game’s architecture that invites the player to care more about the world by imparting its history to them. The most obvious of these are the books scattered around the map, which contain texts that build on the lore of the world, but there are also set pieces like statues, unique buildings, and messages written on walls. More implied is the atmosphere of the space itself. The cities of Lust, for example, may seem like a cold metropolis from a distance. By allowing the player to enter into the homes of its former residents, however, it adds a humanizing aspect to the layer, and raises the emotional stakes when you learn about the fate of all these residents.

While you naturally encounter some of these clues over the course of playing through levels, others take some more thorough investigation. The burden of discovery and interpretation is placed mostly on the player. Though this may cause disinterested players to disengage from the world entirely, it also allows ones who are interested to calibrate their own investment in uncovering Ultrakill’s embedded story and lets them take a more active role in the narrative process.

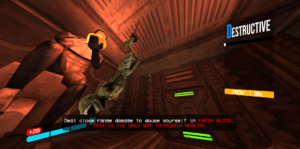

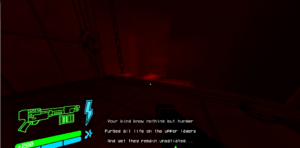

Another big step that Ultrakill takes to make the player care about its world is by letting them affect it. The beginning of the game sets up an oppositional relationship between the player and the NPCs in the world, as the player is incentivized to kill everything they encounter. This is something the game encourages on a mechanical level— number of kills is a metric the player is graded on at the end of each level, alongside other statistics like the time it took to complete the level and the amount of style points they achieved. For players who find their fun in skill based challenges and goal achievement, it becomes relevant to their playthrough to not leave anything alive. Even for a more casual player like myself, who was not trying to get the highest possible grade in every level, aiming for A’s over D’s was something that made its way onto my priority list.  The game’s only healing mechanic, dealing damage at close range and dousing yourself in your enemies’ blood, also encourages a more aggressive style of play. When I found myself low on health, for example, my first instinct was to sprint towards an enemy to punch or shoot them point blank. Often, I would seek out enemies to do this, or even force myself to completely clear a room in a level because I wanted to stock up on health for the next encounter.

The game’s only healing mechanic, dealing damage at close range and dousing yourself in your enemies’ blood, also encourages a more aggressive style of play. When I found myself low on health, for example, my first instinct was to sprint towards an enemy to punch or shoot them point blank. Often, I would seek out enemies to do this, or even force myself to completely clear a room in a level because I wanted to stock up on health for the next encounter.

Indiscriminately shooting everything that moves isn’t necessarily conducive to forming bonds with the NPCs (though they are all also unilaterally trying to kill you, even the ones that talk to you), but it is the primary method through which the player, as V1, participates in the game’s enacted narrative, which tells of the emptying of Hell and the game antagonist Gabriel’s personal character arc, which affects offscreen events in Heaven.  The player, as V1, leaves their mark on both of these plots through the violence they commit during gameplay. While most of Gabriel’s arc is told through cutscenes, the two boss fights the player has with him serve as critical turning points in his story, influencing the trajectory of actions. The player is also irreparably changing the landscape of Hell as they explore it. The game treats each level as literally “emptying” Hell, destroying the remaining monsters and machines that still dwell inside each layer. Even the way the game chooses to portray individual fights builds on this idea: the marks of your battles stick around. The player leaves each space covered in bloodstains, corpses, and bullet marks.

The player, as V1, leaves their mark on both of these plots through the violence they commit during gameplay. While most of Gabriel’s arc is told through cutscenes, the two boss fights the player has with him serve as critical turning points in his story, influencing the trajectory of actions. The player is also irreparably changing the landscape of Hell as they explore it. The game treats each level as literally “emptying” Hell, destroying the remaining monsters and machines that still dwell inside each layer. Even the way the game chooses to portray individual fights builds on this idea: the marks of your battles stick around. The player leaves each space covered in bloodstains, corpses, and bullet marks.  As the player learns more about the history and character of the world, they must also contend with the destruction of the world at their own hands. By working the consequences of their actions into the game’s narrative, Ultrakill invites the player to care by making them a part of its world. It gives each action an underlying existential resonance. Mankind is dead, and the rest of the world is dying. Care about it while you can.

As the player learns more about the history and character of the world, they must also contend with the destruction of the world at their own hands. By working the consequences of their actions into the game’s narrative, Ultrakill invites the player to care by making them a part of its world. It gives each action an underlying existential resonance. Mankind is dead, and the rest of the world is dying. Care about it while you can.

Ethics:

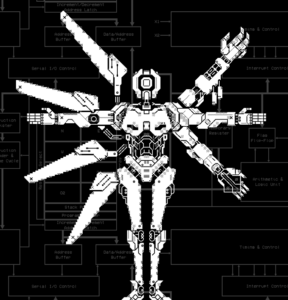

Ultrakill takes place in a world that is explicitly set after humans have all gone extinct, with the only things left being the denizens of Heaven and Hell, and the constructs that humans created. The character that the player embodies, V1, is a prototype of a machine that was originally designed to fight in a human war, before it was decommissioned abruptly upon the end of that war. V1’s body, as well as the bodies of all the robots encountered in the game, echo aspects of human design. Many of the machines, for example, have a very typical humanoid shape—bipedal with two* arms, legs, a head. These bodies reflect what a human designer might view as the form of a standard human body, both in a diegetic sense and in the way Arsi Patala might have imagined a person. All machines do have an innate purpose, since they were built to wage war, but they’re more of a commentary on the goals of humanity than a biological directive.

Ultrakill takes place in a world that is explicitly set after humans have all gone extinct, with the only things left being the denizens of Heaven and Hell, and the constructs that humans created. The character that the player embodies, V1, is a prototype of a machine that was originally designed to fight in a human war, before it was decommissioned abruptly upon the end of that war. V1’s body, as well as the bodies of all the robots encountered in the game, echo aspects of human design. Many of the machines, for example, have a very typical humanoid shape—bipedal with two* arms, legs, a head. These bodies reflect what a human designer might view as the form of a standard human body, both in a diegetic sense and in the way Arsi Patala might have imagined a person. All machines do have an innate purpose, since they were built to wage war, but they’re more of a commentary on the goals of humanity than a biological directive.

What does raise some ethical questions, however, is the depiction of some NPC bodies. Many of their bodies are designed to be grotesque and monstrous-looking, but at times their designs raise some ethical questions about which physical appearances are portrayed as “monstrous”. The filth, for example, have no arms, but limbless people exist in real life. Assigning physical characteristics that people have in real life to game monsters that are associated with sin and Hell can affect the way people are treated in real life, and further contributes to the ostracization of people with limb differences, or other conditions that affect their appearance.

What does raise some ethical questions, however, is the depiction of some NPC bodies. Many of their bodies are designed to be grotesque and monstrous-looking, but at times their designs raise some ethical questions about which physical appearances are portrayed as “monstrous”. The filth, for example, have no arms, but limbless people exist in real life. Assigning physical characteristics that people have in real life to game monsters that are associated with sin and Hell can affect the way people are treated in real life, and further contributes to the ostracization of people with limb differences, or other conditions that affect their appearance.

*V1 gains some additional arms over the course of the game, but still retains its humanoid appearance.