This week I played Super Mario World by Nintendo. I played the Internet archive version on my computer, originally released in 1990. I’d never played this version and I found the gameplay pretty addictive given its combination of being fun while also frustratingly difficult at times. Given I was playing on my computer and not a controller, the control mapping was a little strange and inconsistent at times which was a large source of frustration when I’d be trying to jump while riding Yoshi and press the wrong jump button. That being said, once I started to solidify some of the basic interaction loops, I began to understand and appreciate the narrative and character-building that this game unrolls as you move from level to level. Compared to standalone or more indie games, the character Mario and the narrative built around him is already well established by the time this game is released. Since Mario Bros, Super Mario Bros 2 and 3, and several related games have already introduced this character, this game, Super Mario World, focuses more on building the narrative around supporting characters and the more general society and culture of the “Mario World”. As such, playing this game helps us as players more deeply understand Mario’s role as protector in the scope of his world and the relationships he has with the other whimsical creatures in Mario’s world.

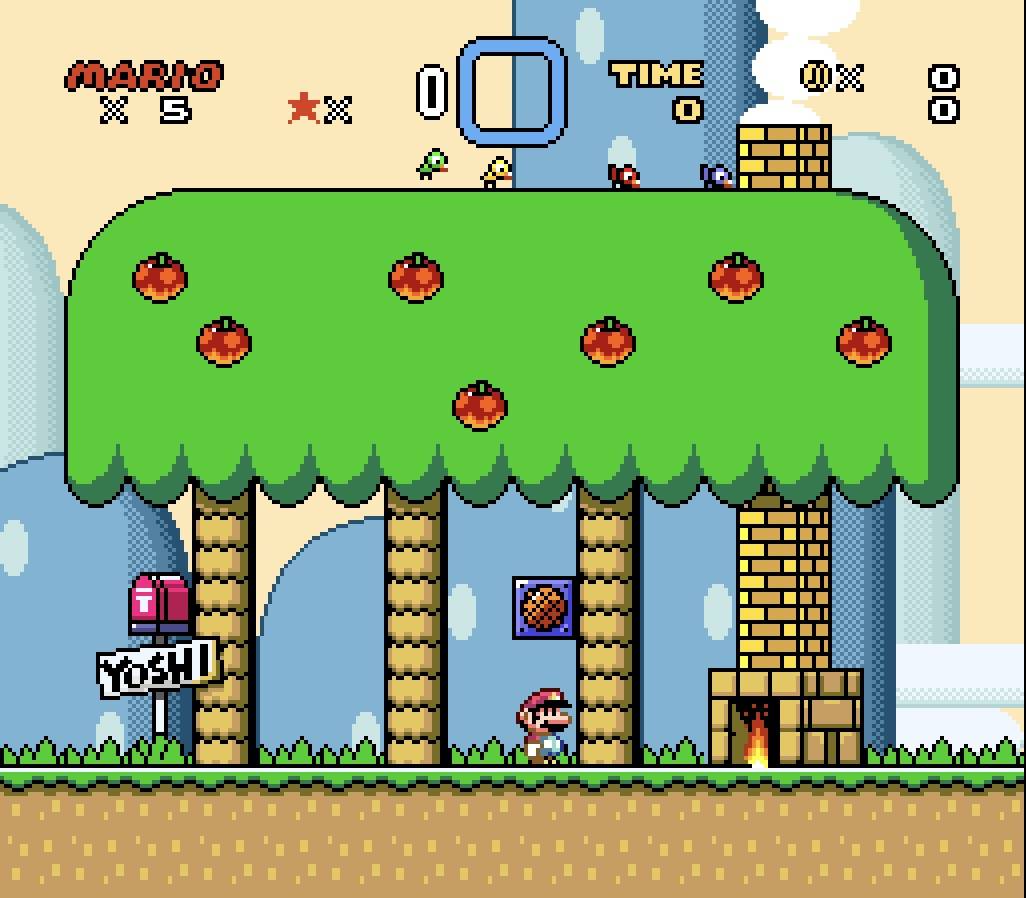

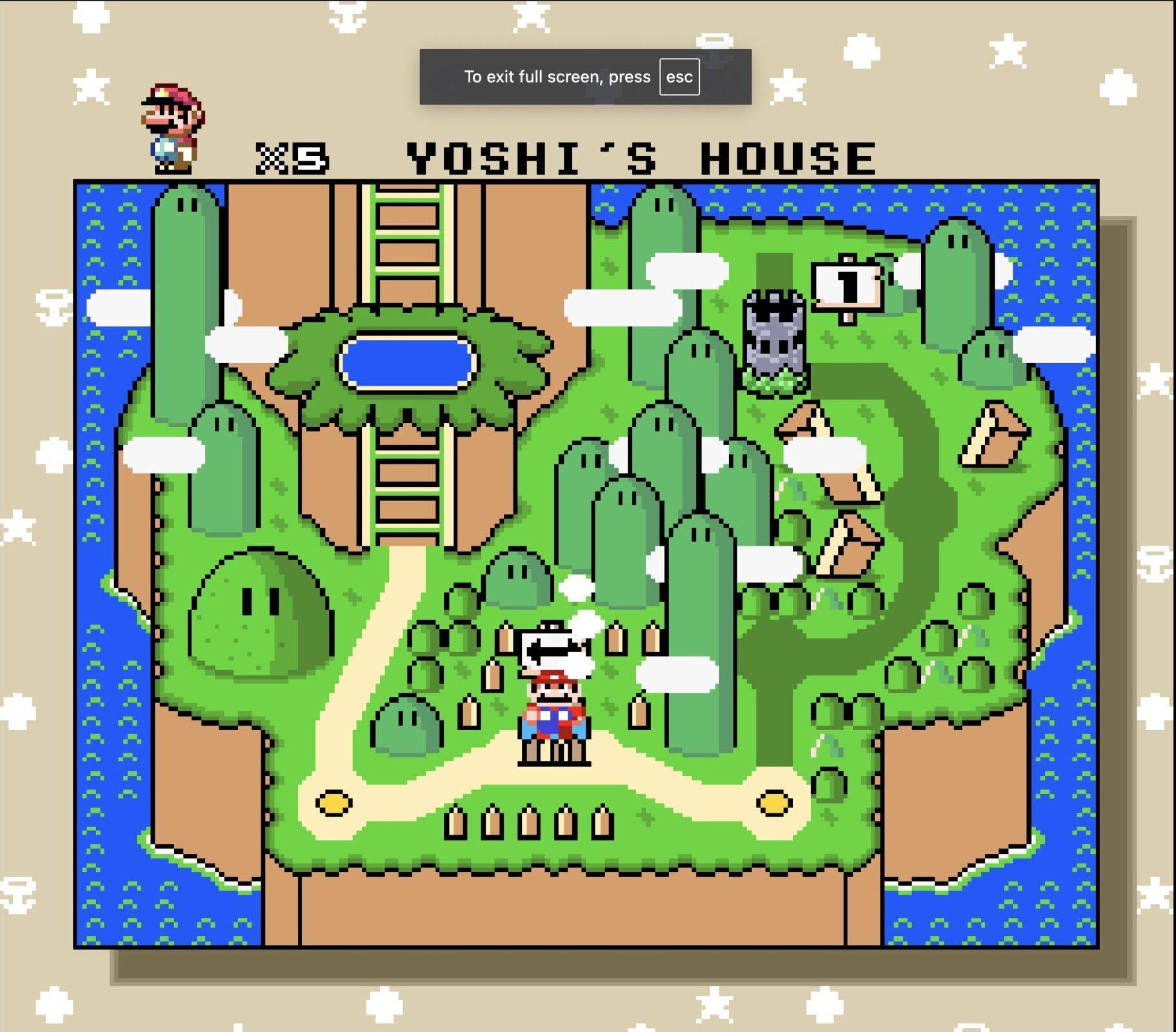

At the beginning of the game, the first narrative panel directs your focus onto this new place we learn is Dinosaur Land. Here we learn the overarching objective of the game is to save Princess Toadstool. In the same location, Yoshi’s House, we also learn that Mario has a dinosaur companion named Yoshi. This first “level” strictly serves as a narrative-building tool as you get to explore the different movement controls and explore this new setting.

From Yoshi’s house, you have the option to go left or right and do the corresponding levels for each direction. This nonlinear play structure gives the player a sense of agency over where they explore. As I was playing, this became a helpful tool for leveraging the intrinsic motivation or explorative curiosity of the player to care about where they go in this new world. For example, if I got frustrated at one level, I could simply go down the other branch in the road and do that level which helped maintain my motivation to keep playing and finding a novel stimulus (whether it be gameplay or narrative).

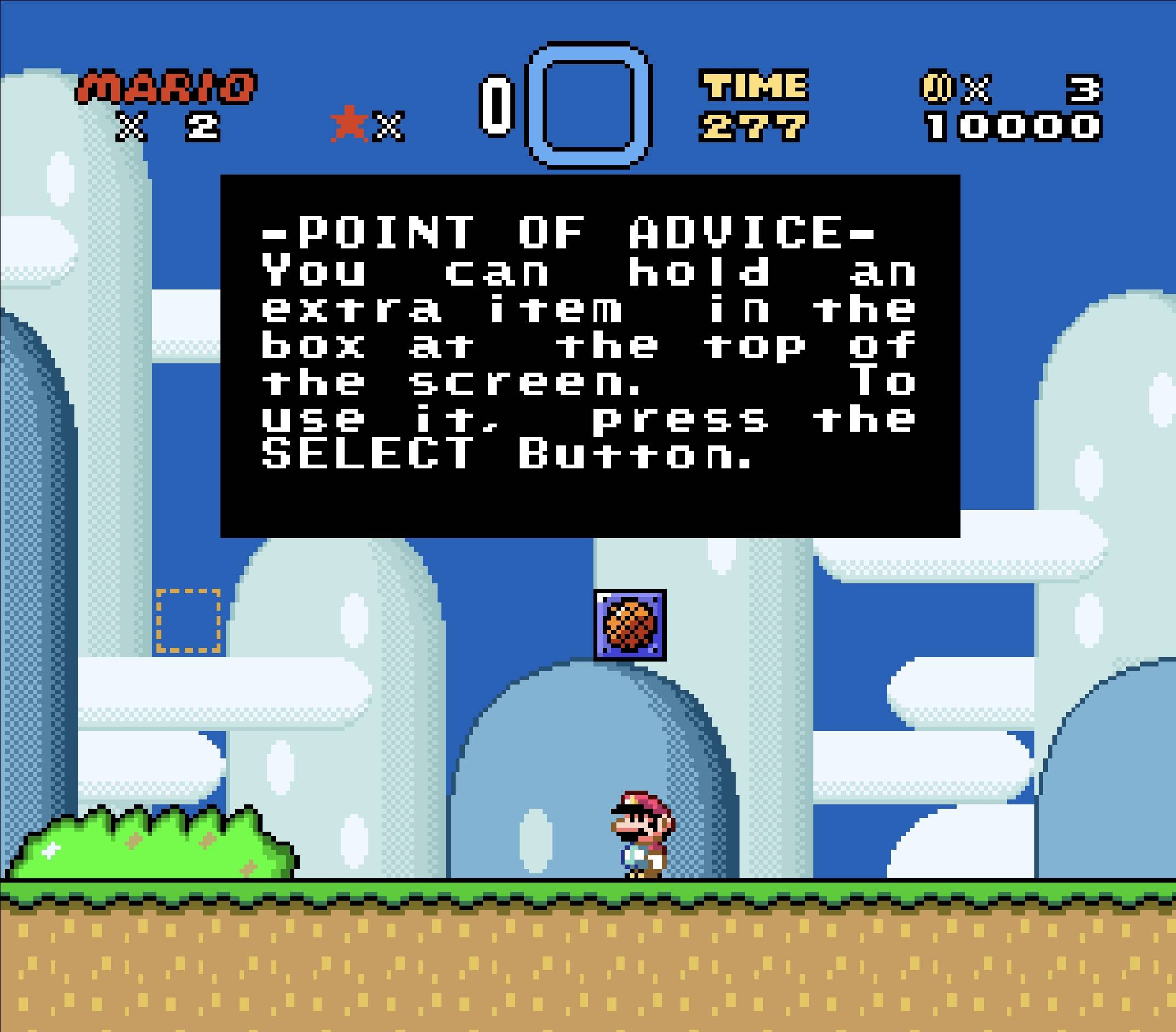

An important element for integrating a new player into the game is teaching them the relevant interaction loops that are necessary for progress in the larger narrative arc of finding Princess Toadstool and defeating Bowser. In the screenshot below, you can see a purplish block that when you jump up into, will make a short text blurb pop up that introduces some relevant skill/interaction loop that’s helpful/necessary for completing this relevant level (and the levels beyond). I thought this was an intuitive design because it leveraged one of, if not the most basic and integral loops that exist in Mario Bros as a means of learning later interaction loops. Also, if you were already an experienced player, you could simply run past these blocks without having your gameplay interrupted by text blurbs, so this design felt very adaptive to what both new and experienced players might want from an onboarding mechanism.

Once you finally find Yoshi, you’re slowly introduced to the new mechanisms (or augmented old interaction loops) that you have when riding Yoshi. For example, with Yoshi, you can swallow enemies and spit them back out as a form of attack. By integrating the familiar loops of jumping and moving left and right with several new, cumulative abilities, it refreshes old mechanics and presents the unique value of these new companions given their unique abilities. Since I’d already visited Yoshi’s house at the beginning of the game, I already had the context for what role he had within the game and why I should be looking for him (he’s a helpful companion!).

While the creatures might be whimsical, the setting of a forest or a castle is familiar and Super Mario World leverages familiar settings to help the player differentiate friend from foe through aesthetics. In the image above, Mario is exploring a green, lush forest that is the home of Yoshi. This bright, pleasant setting helps subconsciously reaffirm that Yoshi is a friend. In contrast, when I enter Iggy’s Castle, you’re met with dark colors, stonework, and fire which again leverages familiar aesthetics to help us understand who the bad guys are. Through explorative agency, well-introduced interaction loops, and familiar aesthetics, Super Mario World invites new players to understand and appreciate the world they’re entering.

While you as the main character play as a human, Mario, many of the villains you meet in Super Mario World are non-human monsters. This is particularly the case for the main antagonist Bowser who is a gnarly-looking turtle guy with sharp teeth and a spiky shell. This depicts a very classic aesthetic and biological distinction between what should be considered “good” versus what should be considered “evil”. When you pitch the turtle monster that lives in a fire-filled castle as evil it’s an implicitly understood design that you don’t have to go to lengths of explaining. Given that countless stories have told a similar narrative of the hero vs. monster (beauty vs. ugly), and many of the creatures with sharp teeth and claws can hurt you, this makes sense culturally and evolutionarily. Narratively, the focus is on understanding Mario’s motivations and characteristics rather than Bowser and as such the lack of humanization for Bowser only aids his vilification. To switch these characters and their roles and be unable to rely on stereotypical aesthetics to frame your hero and villain for you, the narrative becomes a lot more important for helping the player understand and sympathize with a non-human creature like Bowser. Essentially, it boils down to humanizing something non-human. While it may take more context to build an understanding between the player and the story being told, I don’t think much of the underlying mechanics of this game would need to change. I think an interesting rendition of this exact scenario is the newest Super Mario Bros movie where we get to see Bowser become humanized and now all of a sudden it becomes a lot easier for us as the viewers or players to understand and even root for a character like Bowser. All that to say, in the context of Super Mario World, you don’t need to change any of the aesthetic choices for a “villain” character like Bowser as long as your narrative is designed to contextualize and humanize him.