The game I playtested for this week was Hollow Knight, developed and published by Team Cherry, for which players play on PC, Nintendo Switch, PlayStation, or Xbox. The target audience for this game would be players aged 13+ who enjoy challenging platformers and atmospheric exploration with less storytelling.

In the game, the player controls the Knight, an insectoid warrior, who explores Hallownest, a fallen kingdom plagued by an infection. The game is set in diverse subterranean locations, featuring friendly and hostile insectoid characters and numerous bosses, and players have the opportunity to unlock new abilities as they explore each location, along with pieces of lore and flavour text that are spread throughout the kingdom.

[Figure 1: Dirtmouth]

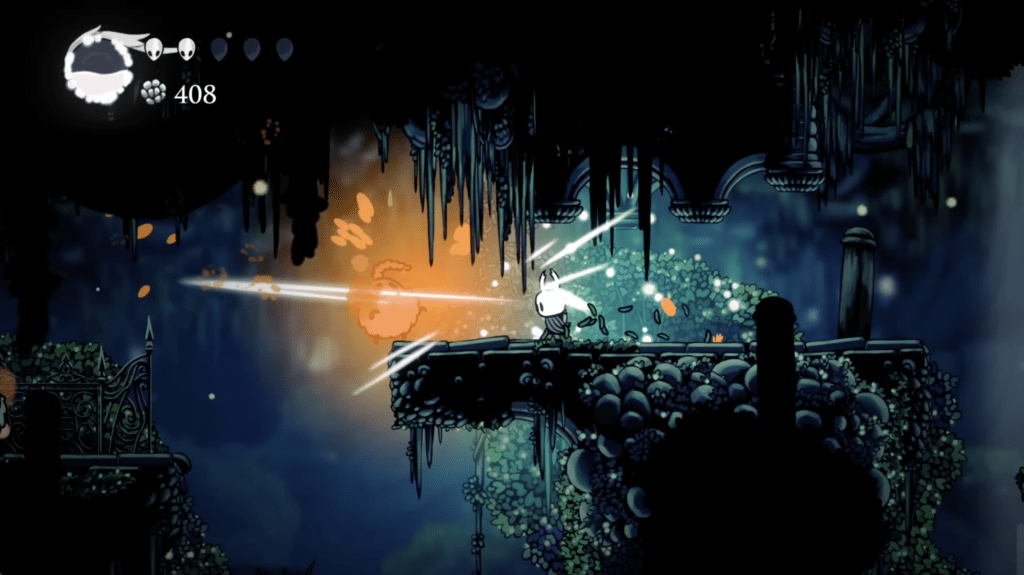

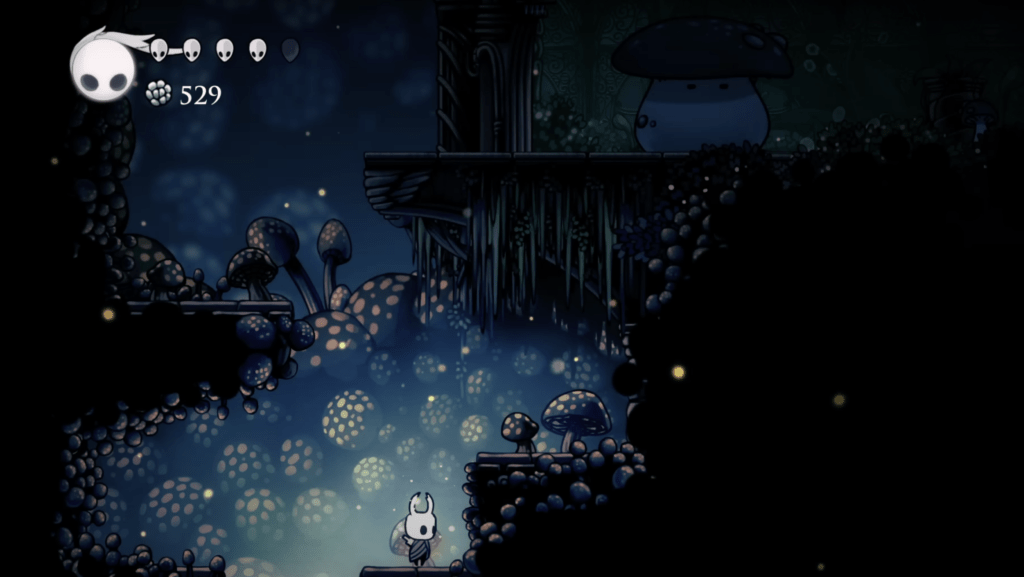

[Figure 2 & 3: Greenpath]

In the figures above, the soft glow of floating spores, the quiet shimmer of background lights, and the purples and blues of the Mushroom Wastes all blend together in a dreamlike haze. The textures are subtle and organic, and yet everything is hand-drawn with intention. The Knight, with its stark white mask and simple cloak, contrasts vividly against this background, both part of and alien to the world it explores. Even the enemies blend into the ecosystem – they feel more like corrupted relics of the world than villains.

But it’s not just the visuals. The sound design is equally refined: ambient background hums, the occasional drip of water, faint insect rustlings, and a score that surfaces only when needed – melancholic piano chords or haunting strings. This audio-visual experience makes the world feel like it’s breathing around me, even when nothing is happening on-screen.

And yet, what surprised me most was how much I cared about this quiet, crumbling kingdom. Gabriela Pereira explains in The Psychology of World Building that a compelling world isn’t just scenery but an ecosystem centered on a character. In Hollow Knight, that character is the Knight; like the child at the center of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model, the Knight is shaped by – and shapes – the surrounding layers of this fallen kingdom. Though they say nothing, their resilience, determination, and moments of stillness made me see Hallownest through their quiet grief. I felt I was moving through memory.

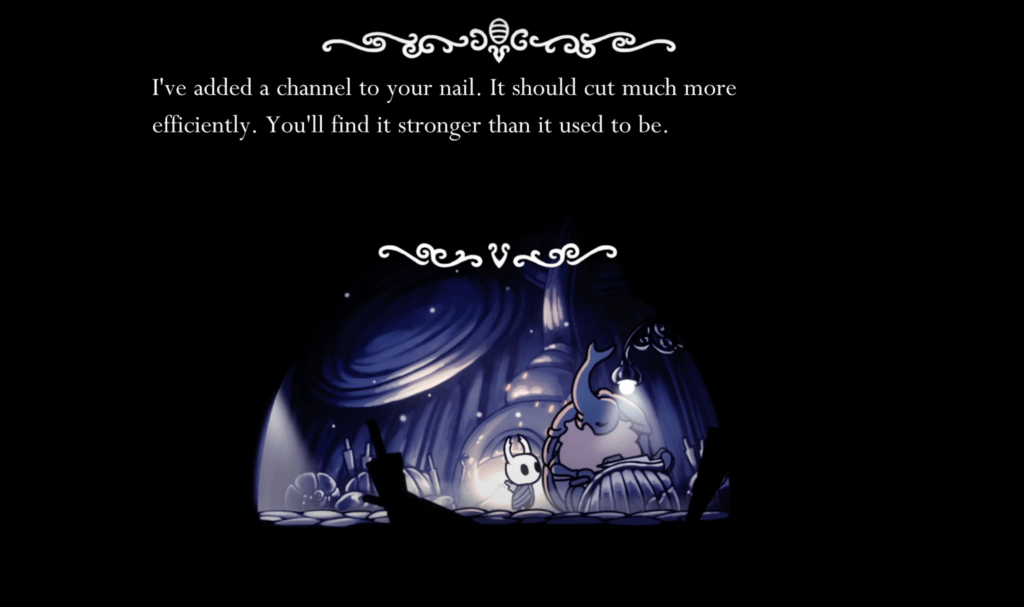

The second layer would be the supporting characters, which add emotional texture to this world. Figures like Hornet, the Seer, and Quirrel are not just NPCs (while I only got to meet Hornet); they are remnants of a declining society. Some, like Zote the Mighty, offer comic relief, while others, like Myla the miner, provide heartbreaking turns as they fall to the infection. These characters serve as anchors in an otherwise isolated experience. Their presence not only moves the story forward but also reveals the world’s emotional stakes.

[Figure 4: Narrative comes in]

Scene-level surroundings (layer three) are also masterfully designed. As Pereira describes, effective world building is not just about filling a space with props – it’s about making the environment responsive to the character’s experience. Hollow Knight does this through spatial storytelling. Deepnest feels unsafe not because of enemy count but because of visual clutter, shaky lighting, and distorted sound. In contrast, the Resting Grounds offer open space and ethereal music, creating a sacred calm. Team Cherry uses sound design, light, and navigation as storytelling tools – the lack of a map in new areas becomes an intentional narrative mechanic, forcing players to feel lost and vulnerable, just like the Knight.

Society and culture help the game unfold its mythology at the fourth layer. Everything is never forced on the player. Instead, I uncovered it in relics, cryptic dialogue, and statuary. Like Pereira’s advice not to take the world’s “insider knowledge” for granted, it never assumes anything but invites players to piece it together. One of the most poignant symbols is the dream nail – a device that lets you read the thoughts of others. Through it, I heard the regrets and dreams of characters and enemies alike.

Finally, the landscape itself is a metaphor for loss. Hallownest is vast, layered, and slowly decaying. Areas like the fungal wastes, the city of tears, or the abyss are not just locations but emotional states. The verticality of the map – its endless descent – mirrors the player’s emotional journey, from curiosity to sorrow to peace.

Ethics

This game raises ethical questions about embodiment and worth. In this game, embodiment is conditional. Their body is designed to be disposable, empty, a “vessel.” I think power here comes not from stats or biological traits, but from experience, memory, and cultural artifacts. The Knight is a vessel – literally. They were created to contain the infection, a being stripped of identity and destiny. Their body is functional. Traits are not biologically “good” or “bad” but are determined by context and cultural mythology. The infection, for example, is not framed as evil, but as a consequence of failed societal control.

Interestingly, players collect charms throughout the game, shaping their identity and abilities. This differs from the other RPG trope, which states that power is innate or inherited. If I were to mod the game, I would experiment with charms that evolve based on how you interact with the world emotionally, such as gaining strength after mourning a fallen ally or after sparing an infected creature. This would align with Pereira’s notion that experiences and relationships, rather than raw attributes, should drive character evolution.