I played The Almost Gone this week for my critical play. It was interesting to compare the narrative and mechanics versus the very similar game I played last week, Tiny Rooms Story Mystery. Both of these games use swiping and tapping mechanics to move around the game space and to interact with items/puzzles placed within the 3D grid “rooms”. An important difference that I noticed between the room-to-room navigation techniques is that you simply tap on doors or labels for adjacent rooms in Tiny Rooms to move while swiping is used to navigate between rooms in The Almost Gone. Since swiping is already used to rotate a room, I would have to be careful how and where I swiped on the screen to properly rotate vs. navigating into another room (which was a bit annoying). A positive difference between these two games is that the puzzles in The Almost Gone were tightly woven into pushing the game’s narrative. In comparison, I felt like the puzzles in Tiny Rooms were a bit generic and irrelevant to the overarching narrative that the game was telling. Because the puzzles in The Almost Gone incorporated narrative-significant objects, I felt like I was playing a more active role in telling the story.

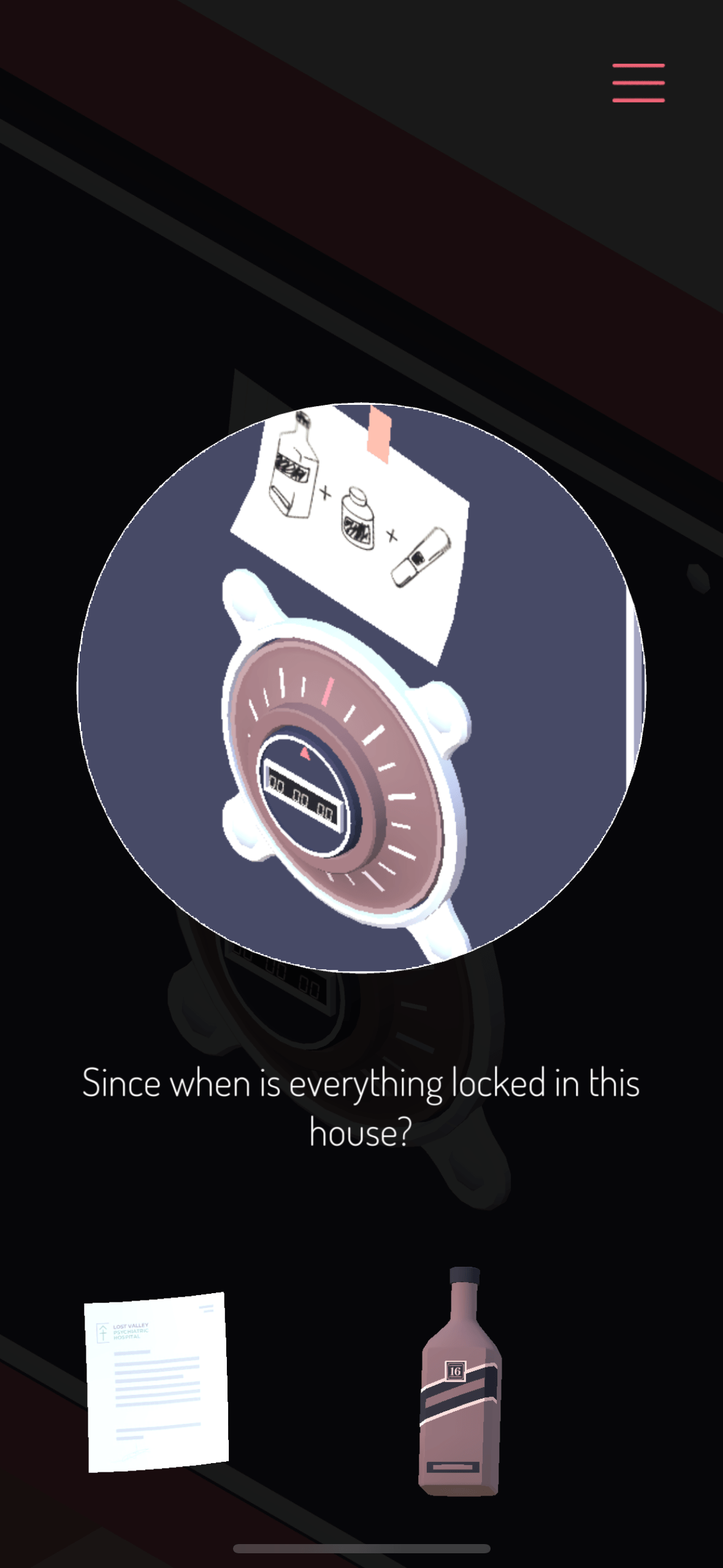

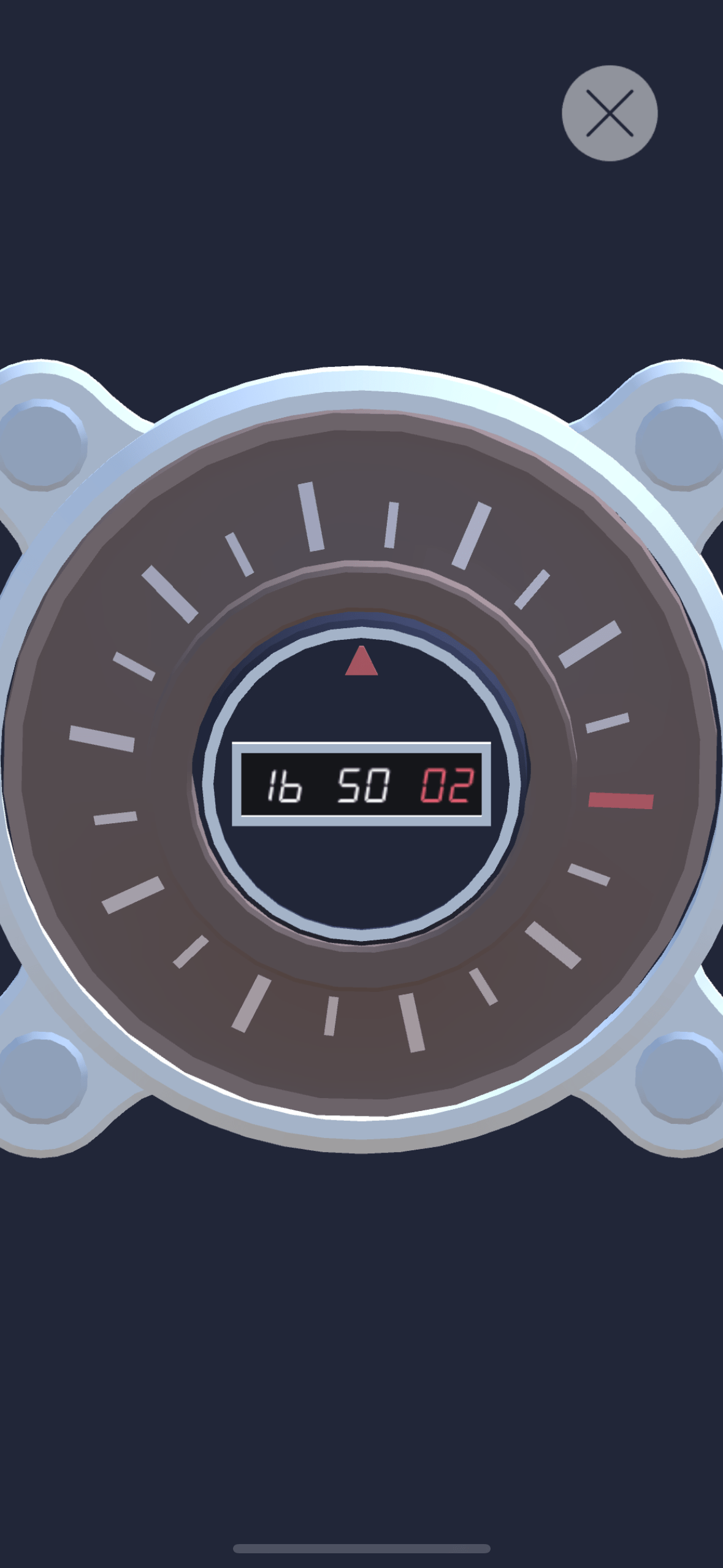

As I mentioned briefly, the mechanics of this game are simple: swipe or tap. While the mechanics are simple, they support the exploratory and problem-solving dynamics of the game as you navigate rooms, tap on and collect items, and create patterns between different objects spread in the digital space. The subsequent aesthetic of thisgame is set in and around a home, neighborhood, and apartment complex (at least through the first few acts) making pattern recognition and puzzle solving feel more familiar and more intuitive. For example, one of my favorite puzzles from the first act is set in the character’s childhood home and is trying to figure out the combination to the safe. Above the safe’s knob is this piece of paper that illustrates a liquor bottle + a pill bottle + a pregnancy test. Scratched out in black are the labels (or screen for the pregnancy test) which provide a subtle hint about where you’re supposed to get the combination from. Once you find each of the three objects, you realize their labels each have a number that you’re supposed to enter into the safe to unlock it.

From this example and my general experience playing this game, the puzzles were mentally stimulating but not difficult to the point of frustration. This was a concept we discussed in lecture, erring on the side of making puzzles too easy rather than too hard, which I felt this game accomplished well. Because The Almost Gone utilized puzzle-solving as the vehicle/dynamic to build and drive the narrative, the puzzles needed to maintain a sense of flow and momentum to be effective. Outside of the puzzle-solving which helped drive smaller/more specific plot points, text screens would contextualize different the different locations you were dropped at (specifically broken into Acts). Relative to Tiny Rooms, I thought The Almost Gone did a more effective job intertwining narrative progression and puzzle-solving.

From this example and my general experience playing this game, the puzzles were mentally stimulating but not difficult to the point of frustration. This was a concept we discussed in lecture, erring on the side of making puzzles too easy rather than too hard, which I felt this game accomplished well. Because The Almost Gone utilized puzzle-solving as the vehicle/dynamic to build and drive the narrative, the puzzles needed to maintain a sense of flow and momentum to be effective. Outside of the puzzle-solving which helped drive smaller/more specific plot points, text screens would contextualize different the different locations you were dropped at (specifically broken into Acts). Relative to Tiny Rooms, I thought The Almost Gone did a more effective job intertwining narrative progression and puzzle-solving.

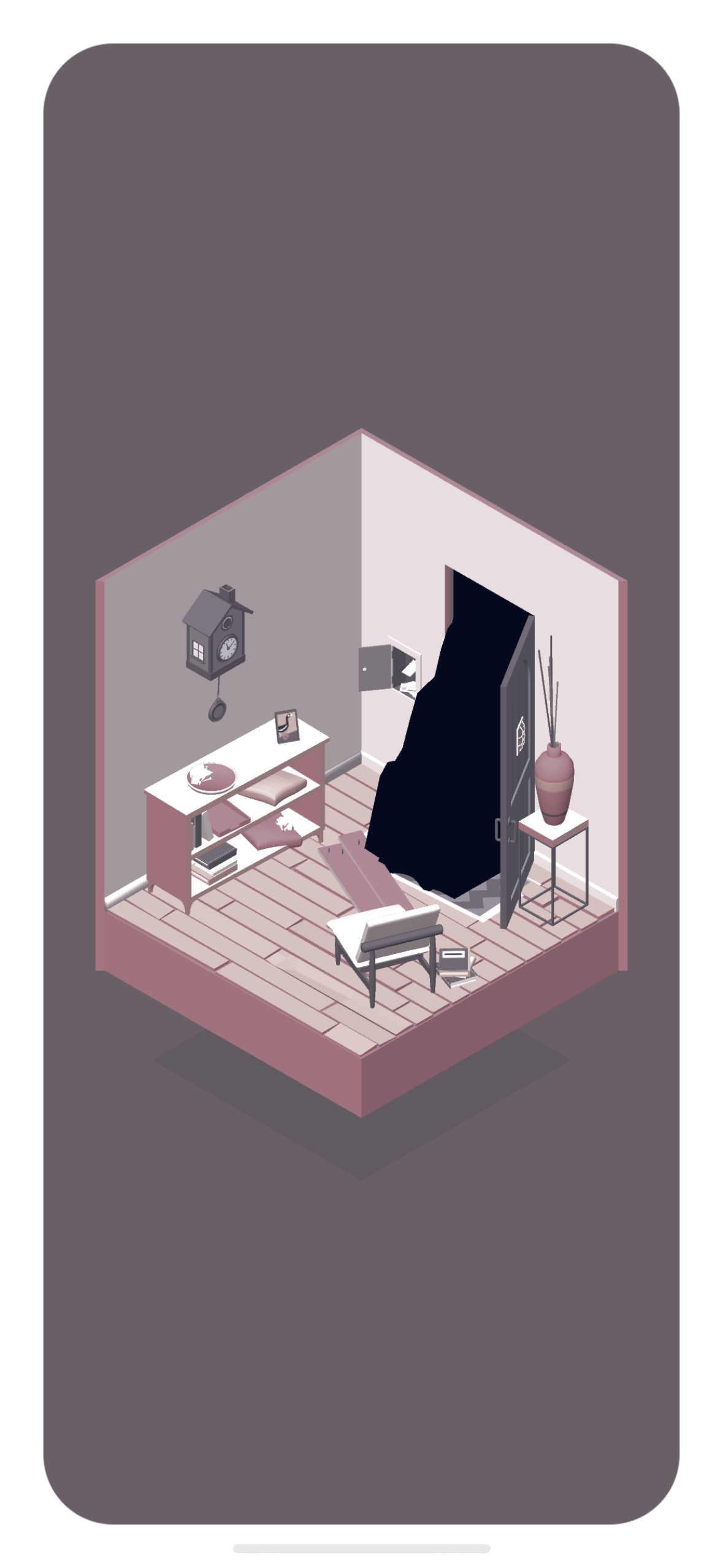

To play this puzzle-style game, it requires you to think outside the box and simultaneously use objects for the function they were designed for while also using objects in unexpected ways, both very traditional puzzle mechanics. Most of the puzzles I solved utilized objects in the way that they were meant to, and similar to how someone might derive a passcode for their safe, you have to find the random objects that the password references. As such, you do have to have a nonlinear form of thinking to solve the puzzles successfully, but for the most part, the designers assume that their players have a general understanding of everyday, household items. For example, (from my experience playing the game) when you find a door locked, the designers expect you to look for a key. When you find a door barred by wooden planks nailed into the door frame, you look for something to pry the wood off. So while the objectives are clear, you’ll often find the objects you need in very unexpected places. Another example is when I was looking for the pregnancy test, it ended up being in the middle of a wedding cake.

I was definitely not expecting this, but I’d argue that no subset of real-world knowledge (cultural, socio-economic) would’ve prepared me to look for the pregnancy test in the cake. It was a theatrical element to drive home a key plot point. So while the designers don’t expect for players to have a specific subset of real-world knowledge, players younger than late high school or college might not have as much success understanding the plot and or the function of the items you’re looking for throughout the game. That being said, this game does a an effective job using text hints associated with “locks” (things to be solved) and “keys” (things used to solve) to nudge the player in the right direction and prime them of the expected function for that object.