Monument Valley, developed by ustwo games, is a visually striking puzzle game that blends optical illusions, architectural surrealism, and minimalist storytelling into a singular meditative experience. At first glance, the game seems simple: guide a silent princess, Ida, through geometric landscapes by rotating platforms, manipulating pathways, and navigating impossible structures. But beneath its serene aesthetic lies a masterclass in game design, where the mechanics deeply shape not only how players engage with the game—but how they interpret its themes of isolation, redemption, and perspective.

Mechanics as Experience

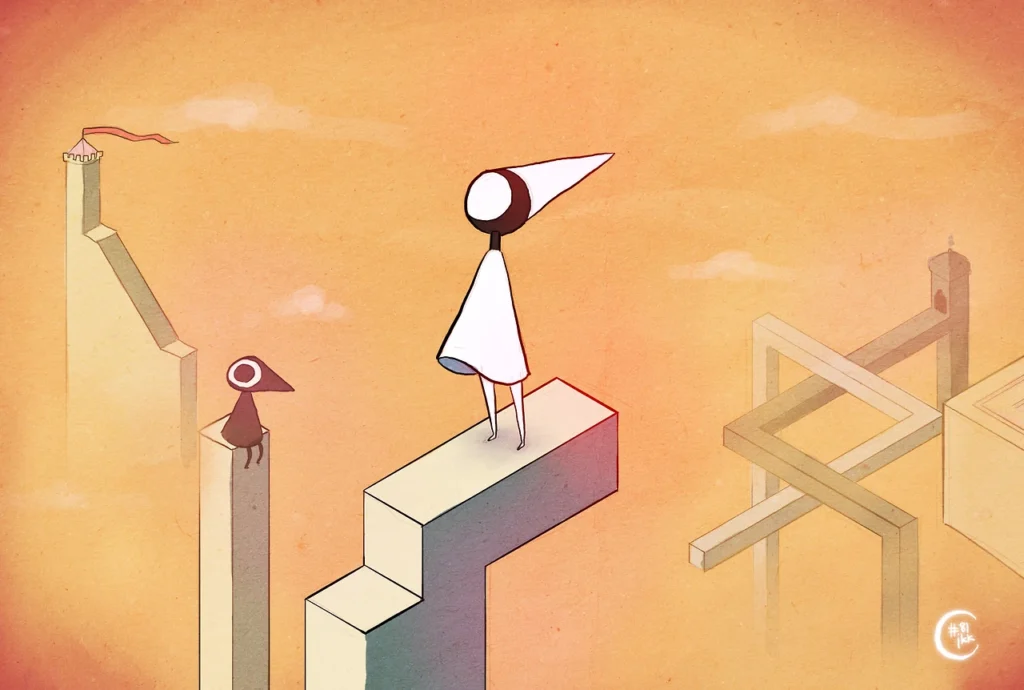

The core mechanic of Monument Valley revolves around optical illusions and impossible geometry—think M.C. Escher brought to life. Paths that look disconnected may suddenly align through the rotation of a platform or the shift of a pillar. These manipulations are often intuitive rather than explicitly taught, creating a sense of wonder when a previously impassable area suddenly becomes traversable.

This mechanic fosters a constant re-evaluation of space. Unlike many puzzle games that reward pattern recognition or brute force logic, Monument Valley encourages a shift in perception. The world doesn’t follow real-world physics; instead, it adheres to visual logic—if it looks like Ida can walk there, she probably can. This principle transforms the game into a quiet philosophical exercise: what is “real” in a world shaped by perspective?

By centering illusion as the mechanic, Monument Valley invites the player to see problem-solving not as a linear process, but as something that requires a change in frame. This is not only clever but emotionally resonant. Guiding Ida feels less like solving puzzles and more like guiding someone through internal transformation—one quiet, mind-bending step at a time. The absence of dialogue amplifies this effect, allowing the mechanics themselves to carry narrative weight. You feel Ida’s solitude, her ritualistic journey, and the weight of her actions—all through the way you turn platforms and guide her along illusory bridges.

A core design principle in Monument Valley: movement as storytelling. The glowing figure, paused at the edge of an impossible staircase, signals a moment of narrative—unlocked not through cutscenes, but through puzzle completion. Players must guide the character to specific locations by solving spatial illusions, and only then does a fragment of dialogue appear. This mechanic turns narrative into a reward for exploration and perception. It reinforces a sense of ritual in progression: each puzzle solved is not just a spatial victory, but an emotional step forward. The game’s mechanics don’t interrupt the story—they are the story, quietly unfolding through presence, placement, and perspective.

The gentle difficulty curve ensures accessibility, but it’s the feeling of solving a puzzle that lingers—not because it was hard, but because it was elegant. The game respects the player’s intelligence without overwhelming them, a rare balance in puzzle design.

The Ethics of Assumptions in Puzzle Design

Yet even in a game so universally praised for its beauty and accessibility, Monument Valley is not free from assumptions. One of the most striking aspects of the game is how it relies heavily on visual-spatial reasoning. To manipulate the puzzles, players must interpret visual cues, predict geometrical transformations, and intuitively grasp how spatial elements might connect.

These are not skills everyone possesses equally. Players with visual processing disorders or cognitive impairments might find Monument Valley difficult or inaccessible—not due to the challenge itself, but because the game presumes a baseline level of neurotypical spatial intuition. In a game that offers no text-based hints or alternative problem-solving strategies, this assumption creates an exclusionary barrier.

Moreover, Monument Valley’s visual language draws heavily from minimalist art, Islamic architecture, and a kind of universalist aesthetic that abstracts away cultural specificity. While this abstraction is intentional—contributing to the dreamlike, allegorical tone of the game—it raises questions: What knowledge is seen as “neutral”? What kinds of cultural references are deemed beautiful and mysterious, versus specific and contextual? The game’s reliance on architectural familiarity (arches, towers, symmetry) assumes a visual literacy that may not resonate equally across global audiences.

In its sequels and DLCs, the game begins to expand narrative themes—particularly in Monument Valley II with motherhood and legacy—but the core design still orbits a very particular ideal: quiet, contemplative solitude expressed through movement and manipulation of pristine space. This is not inherently unethical, but it is limiting in scope.

Final Thoughts

Monument Valley is a triumph of aesthetic and mechanical harmony. Its puzzles aren’t just obstacles; they’re metaphors, each rotation and path a small act of reframing one’s world. But as elegant as its design is, the game’s assumptions about spatial reasoning and universal aesthetics mean that it unintentionally excludes some players while elevating others.

This isn’t a call to erase games like Monument Valley—far from it. Rather, it’s an invitation for designers to consider who their puzzles are really for. Not every game must be for everyone, but every game benefits from understanding its assumptions. And in a world shaped by perspective, perhaps the most ethical design choice of all is to ask: who gets to see the path?