Storyteller is a creative puzzle game developed by Daniel Benmergui and published by Annapurna Interactive. It is available on multiple platforms, including PC, Mac, Nintendo Switch, iOS, and Android. The game is designed for players who enjoy narrative-driven experiences, particularly those who like experimenting with storytelling, cause-and-effect logic, and interactive fiction.

Unlike most puzzle games like Baba Is You or The Witness that challenge players with logic sequences, spatial manipulation, or mathematical reasoning, Storyteller asks players to construct short narratives using a comic-strip format. By placing characters and settings into panels, players gradually discover the hidden rules of storytelling embedded in the game’s system. What emerges is not just a series of puzzles, but a new way of thinking about how mechanics can be used to express cause, consequence, and emotional arcs.

Each level gives the player a title like “A Kiss and a Curse” or “Heartbreak with a Happy Ending.” The goal is to arrange a series of scenes and characters, so the sequence of events visually and logically fulfills that narrative. The characters ‘ behavior depends on who and what surrounds them. What’s particularly fascinating is how this system influences the player’s relationship with narrative. Instead of passively reading a story or making binary dialogue choices, players are constructing stories by understanding how different elements interact. The feeling is closer to programming emotions or designing a miniature play than solving a traditional puzzle. Every successful solution feels like a moment of insight. It is not just into the game’s rules, but into the building blocks of storytelling itself.

This integration of narrative and mechanics is where Storyteller becomes truly compelling. The mechanics are not abstract obstacles but are directly tied to human emotions such as jealousy, love, betrayal, and death. And by framing the puzzles in terms of narrative prompts, the game invites players to think creatively rather than linearly. It encourages trial and error, lateral thinking, and even a bit of performance.

From a formal elements perspective, this mechanic stands out. Unlike games based on movement or time pressure, Storyteller is entirely about sequencing. Characters like “witch” or “prince” carry built-in narrative logic (the witch curses, the prince kisses, etc.), and these affordances act like verbs in a grammar system. The rules are systemic, but the feel is improvisational, which is very much echoing what Robin Hunicke et al. describe in the MDA framework as the aesthetic of expression. The drag-and-drop mechanics and persistent character states across panels dynamics support an aesthetic that makes the player feel like a playful dramaturg or director.

One of the most intriguing mechanical choices that supports this playstyle is the game’s flexibility in puzzle completion. Take the level “A Kiss and a Curse” for example. The player is given a generous number of panels, but it’s entirely possible to fulfill the story requirement using fewer. What makes this particularly compelling is that players can choose the narrative order—some may construct the kiss storyline first and then build toward the curse, while others may reverse that sequence, starting with the curse and resolving it through romance. This flexibility gives players a subtle but meaningful authorial role: they’re not just trying to find the solution, but their solution, shaped by the narrative logic they find most compelling.

Two different ways to complete the same level

This expressive freedom expands even further through the inclusion of optional goals and branching subtasks. For example, in the level “Tiny Gets a Kiss,” there are two extra challenges: Ungrateful Maiden and Prince Saves Tiny. These optional goals act as embedded mini-prompts, each suggesting a specific emotional beat or relationship arc that isn’t immediately spelled out by the main story title. Players are not told how to achieve these goals, only that they are possible. Also, this layered structure does more than just extend replayability. It introduces a powerful design value: multiplicity. It invites the player to explore different motivations, character roles, and even moral framings. Is the maiden “ungrateful” because she ignores someone, or because she chooses someone else? What does it mean for the prince to “save” Tiny? These kinds of sub-goals allow players to experiment with alternative interpretations and outcomes, often discovering surprising emotional logic that still fits within the mechanical framework of the game.

The three different solutions

The standard outcome and two extra challenges

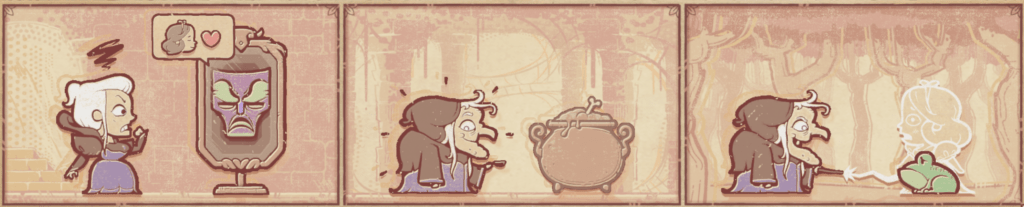

Although Storyteller encourages open-ended thinking, it operates on a bedrock of cultural assumptions. Many of its puzzles depend on a shared understanding of Western narrative tropes—fairy tale logic, romance conventions, and Gothic imagery. The idea that a witch is dangerous, or that a kiss resolves transformation, is deeply rooted in a specific literary tradition. Players familiar with these tropes will quickly intuit mechanics like “the prince kissing the frog revives the maiden,” while others may be confused why certain combinations cause love, death, or revenge. The following picture is a specific example. In this sequence, where the witch wants to turn the princess into a frog, the transformation only works if the witch first changes into her older, hag-like form. This requirement isn’t explained directly, and players may struggle to understand why the spell fails otherwise. It reveals how some of the game’s internal rules are rooted in unstated narrative conventions, which reflect fairy tale logic but might not be intuitive for every player.

This connects to course discussions about embedded values in design. Every mechanic encodes assumptions about how the world should work. In this case, Storyteller encodes a romantic and moral logic: kisses resolve conflict, betrayal is a twist, witches are antagonists. These systems are not “wrong,” but they are not neutral either. As a result, the game implicitly favors players with certain cultural literacy and emotional familiarity, even as it appears to offer wide creative freedom.

In conclusion, Storyteller demonstrates how puzzle mechanics can be used not just to challenge logic, but to shape meaning. Its elegant system invites creativity, experimentation, and reflection. By allowing multiple paths to success and embracing narrative ambiguity, the game encourages players to treat puzzles as expressive tools. Yet at the same time, it reminds us that even the most open-ended systems are built on frameworks, and those frameworks reflect choices about what stories matter, and who gets to tell them.