Name: Life is Strange; Target Audience: Ages 16+, people who have or are experiencing high school and understand the stereotypes/tropes; Creator: Dontnod Entertainment, published by Square Enix; Platform: PS3/PS4, Steam (PC/Mac), Xbox 360/One, Mobile

This week, I played Life is Strange, a 2015 indie walking simulator and mystery adventure game developed by Dontnod and published by Square Enix. My partner has suggested this game to me for quite some time, emphasizing its effective storytelling and the weight of the player’s choices. After playing it for my Critical Play, I understand why they suggested it so strongly! Life is Strange balances many different themes in its narrative extraordinarily well, and I hope to learn from its narrative structure to improve the narrative in my team’s P2.

Life is Strange‘s developers seamlessly weave together mystery and mechanics through the combination of the decisions made by the player and the ability the main character gains at the beginning of the game. In this way, they create a mystery surrounding Max’s ability as well as around the consequences of commiting to your decisions. The physical architecture of the setting further emphasizes these mysteries by implementing constraints and messing with the player’s sense of familiarity.

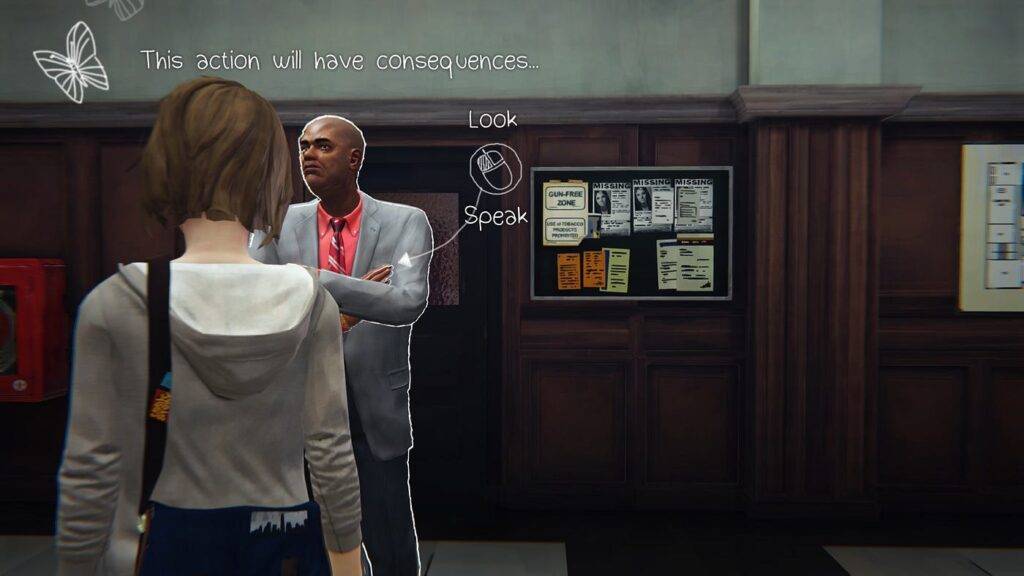

The first mechanic the player has at their disposal to explore the mystery of Life is Strange is making decisions on Max’s behalf. These decisions range from speaking to classmates and teachers to setting up elaborate schemes to spill a can of paint on the school bully to get into Max’s dorm. On its own, decision-making creates its own sense of mystery, as the developers have included a helpful yet ominous UI popup telling the player “This action will have consequences…” (Fig. 1). However, it is not until combining this mechanic with the second main mechanic that Life is Strange adds depth to its mystery.

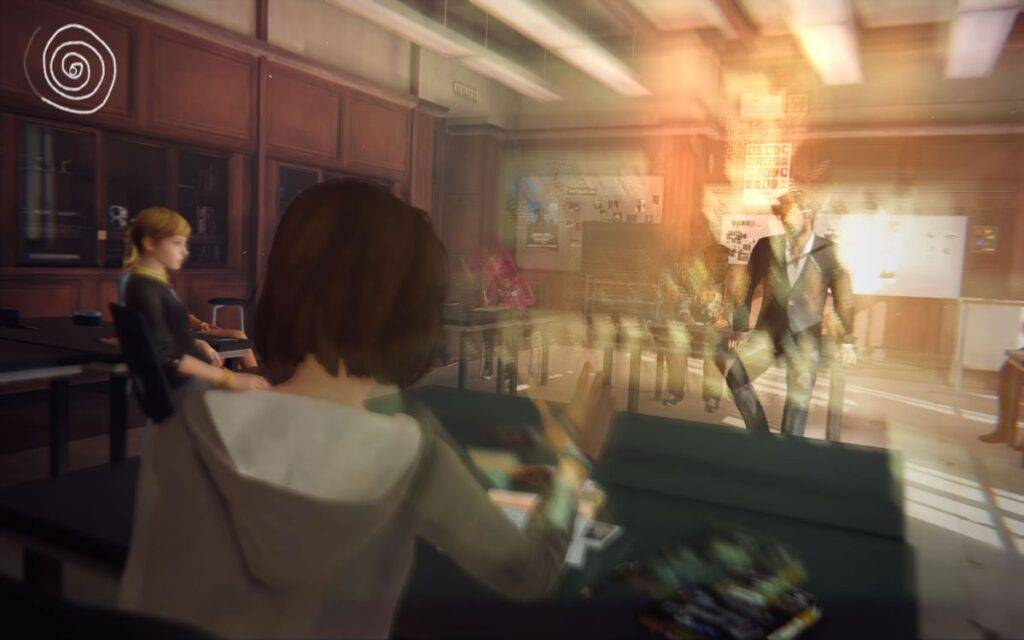

The second mechanic Max gains at the beginning of the game is the ability to rewind time. Typically, this rewind ability does not allow for Max to rewind time for too long — just a handful of seconds (Fig. 2). However, these crucial seconds of rewind are enough to fundamentally change the way the player approaches the game. For instance, a player that is interested in listening to every single line of dialogue recorded for a singular interaction can do so by making a choice (1st mechanic), watching the scene play out, then rewinding (2nd mechanic) and making a completely new choice. In this way, players can explore and experiment with different choice combinations as they progress through the story, correcting small mistakes or changing the direction of the story if they so choose.

I find this combination of mechanics incredibly clever, as it creates a broader mystery for the player beyond the mystery of the two independent mechanics. With the inclusion of the rewind, making a decision in the short term doesn’t feel like it has as much weight, as you can simply rewind and make a different choice. However, with these choices also come long-term consequences that often do not appear until hours (and several play sessions) after you’ve made the decision. As a player, it makes you consider: what kind of world have I created by choosing to do the things I’ve done, and how could I have changed this for the better or for worse? Although this meta narrativization is typically an emergent narrative type, due to the thought put into how these mechanics interact, this experience is fully embedded and expected by the developers. I hope to create something like this for P2, which allows for players to not only reflect on their choices within the game but also reflect on how these lessons could impact their day-to-day life.

This communication between the game and the player on the broader meta narrative that pushes the mystery forward is emboldened further by the architecture of Life is Strange. Although there are interesting things to say about this game’s physical architecture, I first want to discuss how the game itself works as narrative architecture for the story by providing constraints. The opening section of Life is Strange takes place in a prestigious arts high school in the Pacific Northwest, and as such the play area is made up of many distinct areas (i.e. the dorms, the academic buildings). The game often imposes constraints on the player through Max, especially when trying to enter an area that the story isn’t ready for us to visit yet, by having Max comment out loud on how she doesn’t need to be in that area. Not only does this gently guide the player into staying in their current area, but it also feels like a natural way Max would think if she were straying too far away from the task at hand, keeping the player fully immersed and engaged with the story without feeling like the game is preventing them from doing something they want to do.

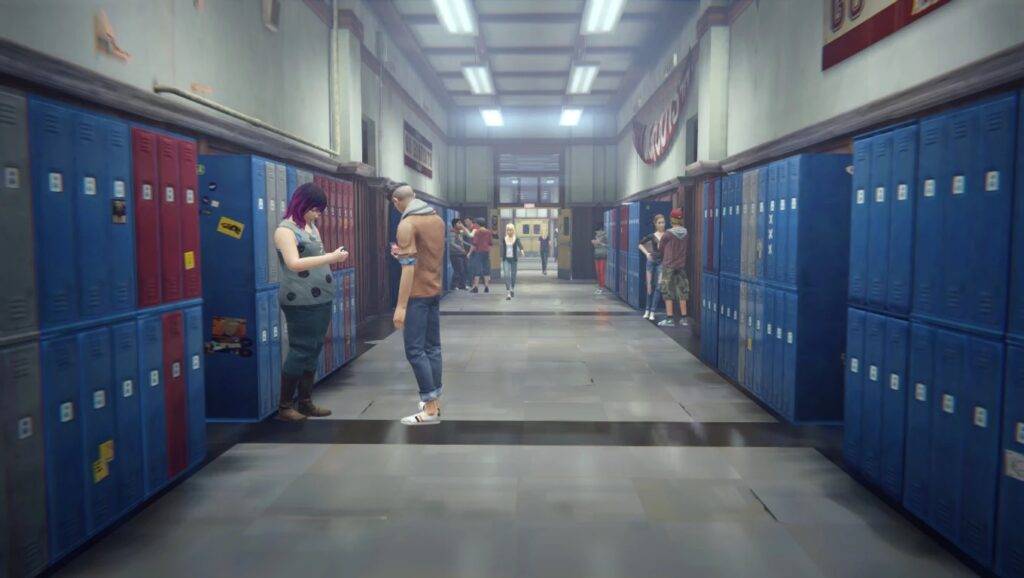

Additionally, Life is Strange‘s physical architecture increases the player’s immersion in the world by messing with our sense of familiarity. Although the first section of the game is set in a high school, which includes many stereotypical high school drama tropes, the high school’s aforementioned prestige creates a kind of distance between the player and the setting. Most people playing Life is Strange have likely been to high school, but the vast majority likely have never even stepped foot in a high school as prestigious as Blackwell. However, this is also Max’s experience, as she tells the player through her journal and internal monologue that she only is able to attend this high school because she got a considerable scholarship and only enrolled in her senior year. Since the player joins the story only a month into her time at Blackwell, it makes sense that her and the player feel like fish out of water as we feel the cognitive dissonance of familiar aspects of the genre (lockers, scary bathrooms, dances [Fig. 3]) with completely alien additions (dorms, bullies that own the school). Although Max has her own voice and her own desires, this distance from Blackwell makes Max an immensely more relatable protagonist and adds another layer to the mystery, as neither the player nor Max know what will happen next at our first year at Blackwell.

Through P2, I would like to use both of the highlighted effects — mechanics and architecture — to create a stronger connection between a main characterthat already has desires and a player that might want something different out of their own lives but still manages to find a lesson to be learned that they can apply to their own life.

Although I am not disabled, I found an interesting article by a person with a hearing disability from a website that rates games based on their playability for people with disabilities (link: https://caniplaythat.com/2019/03/21/deaf-game-review-life-is-strange/). In this article, the reviewer remarks on the customizability of the subtitles thorugh size and letterboxing, as well as the italicization of inner monologue that distinguishes itself from regular dialogue. However, they also mention that since the subtitles don’t include speaker labels, it makes it annoying to try and figure out who is speaking so the player can contextualize what is being said. An easy way to make the game more accessible to those with hearing impairments would be to add speaker labels. Additionally, since this game is incredibly dialogue (and therefore text) heavy, another simple accessibility addition could be to implement a dyslexic-friendly font alternative in the subtitle menu for those with dyslexia.