Artist’s Statement

With our game, Filibuster, we sought to create a fast-paced party game for all types of people. It’s designed to be accessible and deeply social. Through improvised speech guided by the setting and those playing, we figured that it could fit any setting. Through its name, we wanted to try to imitate the idea of actual politicians filibustering and how they attempt to hold the floor through exaggerated speeches. By assigning lists of words to players, we attempt to create funny situations where the players have to creatively weave together sentences in order to gain as many points as possible. For example, players may have to try to shoehorn the word “euthanasia” into the situation “girls night out” leading to laughter and light-hearted mood for those playing the game. Opposing players serve as both opponents and audience, as they try to listen closely to figure out the speaker’s word. This dual-role mechanic allows for a variety of gameplay and friendly competition. Ultimately, Filibuster, aims to celebrate and encourage the awkwardness, yet humor of public speaking.

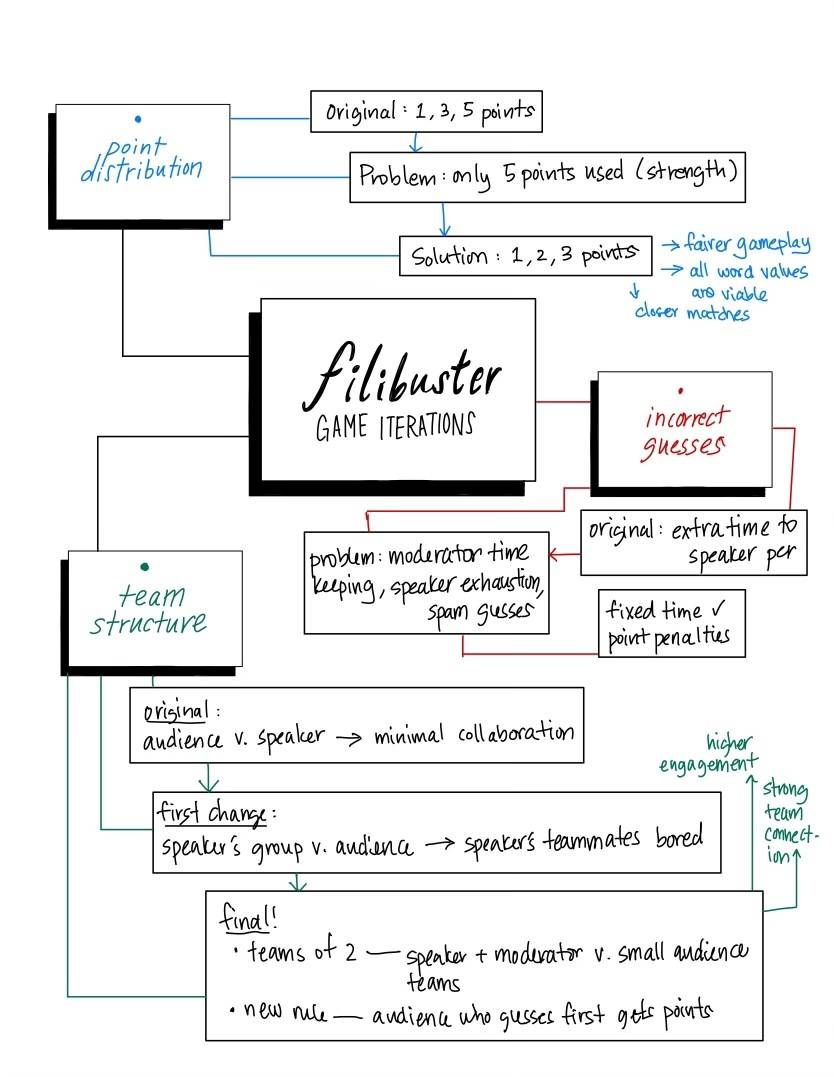

Concept Map

(Initial prototype design – has the same functionality, but without style)

Initial Formal Elements and Iteration History

Throughout P1 our team iterated extensively, particularly with disincentives for incorrect guesses, team structure, and point distribution.

Incorrect Guesses

Originally, the name Filibuster was given to our game due to the fact that one of our main formal elements was that the Speaker was given extra time (between 5 and 10 seconds) to speak when someone guessed their word incorrectly, allowing the Speaker to continue accruing points with extra time. This mechanic was thematically cohesive with our game, but unfortunately through our first playtest it became unwieldy for two reasons: 1) the Moderator would often struggle to keep track of the extra time accrued due to the volume of incorrect guesses from the Audience, and 2) since the only downside for guessing incorrectly was giving the Speaker more time, the Audience realized that they could just continue guessing words until they guessed the correct words. This mechanic created a dynamic in which Speakers would often accrue.

These mechanics created a dynamic in which the Speaker would often accumulate over 30 seconds of extra time, but would be unable to use any of it because the Audience would simply keep guessing and stop the speech by the 40th second of the original time. Speakers communicated that this frustrated them, as they felt that they had put a lot of effort into misdirecting the Audience and encouraging incorrect guesses only for the Audience to continue throwing random accusations until something stuck. Additionally, even if the Audience was not interested in approaching the game in this way, Speakers would often communicate how although they could figure out how to speak for around 60 seconds, speaking for over 60 seconds felt exhausting and they often couldn’t think of what to say (especially if they had over 30 seconds of extra time). Seeing as one of most important values from the beginning was creativity and decision making, the ability to circumvent this was something that we strongly wanted to remove.

In response to this, our team decided to implement a point system with incorrect guesses instead, leaving the time fixed for the Speaker. During our second playtest, we experimented with deducting points from people or teams that guessed incorrectly. Unfortunately, this created issues with teams having negative point values if they continuously guessed incorrectly, with no rule with how to deal with negative points. During our third playtest, we decided we would award points to the Speaker’s team with 1 point per incorrect guess. Although this worked to disincentivize players from guessing wildly, we still felt the group would often guess too freely because they weren’t scared of a single point increase. Finally, we updated this rule by awarding points equal to the Speaker’s chosen word value times the number of incorrect guesses. This approach successfully disincentivized the Audience from shouting every other word the Speaker said, giving more weight to each guess and not only allowing the Speaker more breathing room to speak but also reward them for misdirecting the audience.

Team Structure

Our first playtest of 6 people saw Filibuster as a game of all against one (Audience vs. Speaker), with one Moderator that was outside the game and only around to make sure rules were being followed. However during this, we saw that many audience members would communicate with each other, creating an unintended sense of fellowship. This was something that we didn’t anticipate. Initially, we only cared about competition on an individual level, however, after witnessing this, we decided that this would be one of our core values to dive into and explore.

In response to this, we decided to split players into teams to further encourage collaboration and satisfy our psychogenic need for affiliation. During our second playtest of 6 people (2 teams), we split players into two groups: one group would be the Audience and would guess as usual, and the other group would be the Speaker’s group, with one Speaker and one Moderator. Although this mechanic did improve collaboration as each Audience team was much more heavily incentivized to work with their partner instead of against them, the players on the Speaker’s team without a role (in teams of more than 2 people) expressed that they had nothing to do during their Speaker’s turn other than just sit and wait for the turn to end.

This feeling was opposite of our intended outcome for this game, so for our third playtest of 6 people (3 teams of 2) we split players into teams of 2, giving the game a preference for even-numbered groups. During this iteration, one team of 2 would be Speaker and Moderator, and each other team would be a distinct Audience. This solved the problem of having group members on the Speaker’s team who felt like they had nothing to do during the Speaker’s turn, as now the only two team members were incredibly engaged in either speaking or keeping track of points and incorrect guess counts. We also introduced a rule during this playtest that would award points to the team in the Audience that guessed the word correctly first. This encouraged teams in the Audience to collaborate heavily among themselves while misdirecting and confusing other Audience teams by saying the wrong word on purpose without making a formal guess. By increasing the scope of the competition from Audience vs. Speaker to Team vs. Team vs. Speaker, players remarked that they felt much more engaged and much closer to their teammates than in previous iterations.

Point Distribution

The first couple iterations of Filibuster were fairly straightforward in terms of point values. Each word card had three words valued at 1 point, 3 points, and 5 points. Although it was difficult to tell during the original two playtests, these values created a dynamic in which Speakers were completely disincentivized from trying the 1- and 3-point words. However, as was mentioned by one of the playtesters during our third iteration, “it’s much easier to say one word for 5 points than it is to say 5 words for 5 points, regardless of the word chosen.”

During this playtest, the team in first place had almost double the points of the team in third place simply because the first team had gotten lucky on their first round and said a 5-point word 3 times, whereas the second team chose a 3-point word and got caught the second time. This created a dynamic in which the last place team would fall farther and farther behind each round because they’d try to go for safer words and still get caught in a similar amount of time.

Although we considered making the 1-point words even easier and including prepositions and grammar words (e.g. “like,” “the”), we realized that these words were simply too integral to any speech that making them keywords would be unfair to the Audience and be simply unfun. In response to this feedback, for our last playtest we changed the values to 1 point, 2 points, and 3 points. By tweaking these point values, players were encouraged to consider all three words as options instead of going directly for the 5-point word every time and saying it at least once as a first order optimal strategy. Additionally, this point adjustment improved the point distribution among teams, making games feel more neck and neck instead of having one team run away with the entire game after one good round. This change kept all teams engaged with the game as they all felt like they had a shot at winning, encouraging them to try new strategies when speaking or guessing.

Overall, we saw many of our formal elements stay the same with minor changes like point values, while the overall goal of gaining the most points, and methodology in doing so (repeating the word as many times as possible) stayed the same. The only major change was the shift from incorrect guesses adding time to incorrect guesses giving the speakers points. In terms of values, we still strongly believe in creativity and competition, which we were able to improve upon with our changes to our formal elements. The only value that we added was that of fellowship, which we now believe to be an essential part of our game.

Printable Prototype

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KfEp2uUGP4YRuRcVj7kNvvyqVCZajj8r/view?usp=sharing

Video

Link to video (https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KattLx2CQC2wgHAnwMXvwoZosHUqIcP7/view)

Citation:

Front cover illustration by Terry LaBan