When people think about video games, they often picture action-packed moments, intense combat, or fast-paced decision making. But walking simulators offer something totally different. Instead of focusing on winning or overcoming enemies, these games slow everything down. We can explore at your own pace, paying attention to the environment, the atmosphere, and the story that unfolds around us. There might not be any puzzles to solve or battles to fight, but somehow the emotions land even harder.

I played What Remains of Edith Finch, a game I’d heard about for a long time but never found the right moment to start. It was created by Giant Sparrow and it can be played on PC or iOS. It surprised me with how deeply it pulled me in. Instead of using cutscenes, dialogue trees, or branching paths to tell its story, this game uses something much simpler: walking. Moving from one room to another becomes the central storytelling mechanic. It evokes emotion like narrative, fantasy, and discovery, with a touch of expression, and removes common game objectives like win conditions or opponent rules.

Walking in this game isn’t just a way to get around. It’s how you listen, how you remember, and how you process loss. Every step you take pulls you deeper into the history of the Finch family, and every room you enter reveals a life, a memory, and eventually, a death. That slow movement through the house becomes a kind of emotional pacing and allowed you to absorb the quiet sadness and surreal beauty of each story.

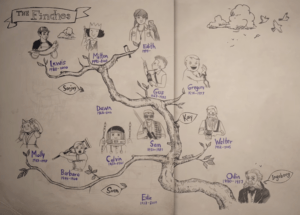

Family Tree

Family Tree

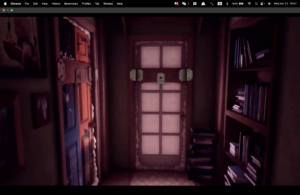

From the moment you step into the Finch house, you realize this isn’t a story the game hands to you — it’s one you uncover. The house feels alive, like a museum of grief, and each room you enter is frozen in time, filled with personal objects and atmosphere. As you crawl through passageways and unlock hidden doors, you’re not just uncovering secrets, but stepped into someone’s life. In each story, the game also has different mechanics, like a comic book, a fish-cutting job, a horror tale told by a child, which keeps everything fresh while still feeling cohesive.

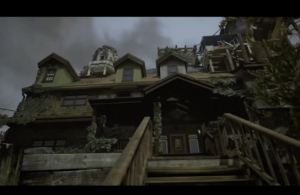

The Finch house and room

The Finch house and room

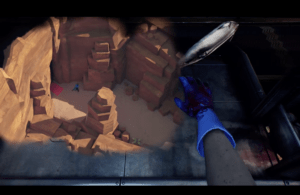

What makes it especially engaging is that the stories are never fully spelled out. Each one is hinted at through fragments, metaphors, and visual storytelling — leaving room for interpretation and imagination. That space to wonder is part of the fun. You’re not solving a puzzle with one correct answer. You’re piecing together a family’s emotional history, and that makes every discovery feel personal. The story of Lewis Finch hit me the hardest. You’re controlling two things at once: his repetitive job at the cannery with one hand, and his fantasy world with the other. Eventually, the fantasy takes over. You walk him right to the moment he loses himself — mentally and physically. It’s tragic, and the fact that you walk him into that ending makes it hit harder.

Lewis Finch’s sequence

Lewis Finch’s sequence

And that’s what makes walking such a clever narrative mechanic. It becomes a kind of quiet permission — you’re not rushing, you’re remembering. You’re not solving, you’re witnessing. The lack of violence, time pressure, or goals creates space for empathy. As the MDA paper puts it, you’re not just playing a system — you’re building behavior through interaction.

Within the walking simulator genre, many games share a quiet, introspective tone and prioritize environmental storytelling over traditional gameplay mechanics. Games like Gone Home, Firewatch, and The Stanley Parable all ask players to slow down, observe, and uncover meaning through exploration. However, What Remains of Edith Finch stands out for the sheer variety and creativity in its storytelling format. While other walking sims often rely on a single consistent environment or mechanic, Edith Finch reinvents its gameplay style with each family member’s story with shifting genres, visual styles, and controls to match the emotional tone of the tale being told. This creates a rich, layered experience that feels more like an interactive anthology than a linear exploration. Where many walking simulators focus on subtle narrative discovery, Edith Finch goes further, offering surreal, metaphorical sequences that transform ordinary moments into deeply symbolic reflections on life and death. Its ability to remain cohesive despite its variety, and to move seamlessly between realism and fantasy, is what makes it a defining work in the genre.

Comparing this to a game like Resident Evil, the contrast is clear. Resident Evil also tells a story. In fact, a much bigger, more complex one in terms of world-building. But the experience is entirely different. Resident Evil uses violence to drive almost everything: the tension, the fear, the stakes. You’re constantly on edge, waiting for something to attack you, and your survival depends on how fast and precisely you can shoot, stab, or escape. I only felt a sense of relief when the game paused for a cutscene. But in Edith Finch, there’s no combat, no enemies. Each story ends in death, and the tone can be dark and haunting, but it never feels violent. It’s proof that death doesn’t always have to be brutal. Sometimes, it can be poetic.

Instead of fearing for your own life, you’re learning about people who are already gone. You can’t change what happened. You can only walk through it. That shift makes the experience feel more real. In Resident Evil, violence is a mechanic. In Edith Finch, death is a fact. That changes everything. You’re not the hero or the survivor — you’re simply a witness. And through that, the game invites you to slow down and reflect instead of reacting.

In the end, What Remains of Edith Finch shows that walking, something so simple, can be one of the most powerful tools in storytelling. By removing traditional gameplay elements like combat or puzzles, the game creates space for emotion, reflection, and empathy. It invites players to not just play, but to listen and feel. It offers a quiet, poetic experience that lingers long after it ends. It’s a reminder that games don’t always need to be loud to be impactful. Sometimes, all it takes is a slow walk.