Among Us, developed by InnerSloth, is a social deduction game where crewmates and imposters must outwit one another, race to complete their tasks and eliminate the crew, respectively, and avoid being killed or voted out. Though its target audience is explicitly for players 10 and up, as a unilateral competition, zero-sum game, Among Us appeals to any and all players that thrive on competition and challenge aesthetics with a dash of fellowship. I played Among Us on my phone; however, it can be played on multiple digital platforms, such as consoles, PCs, and even VRs. One would think that as a digital game that can be played online, Among Us draws a magic circle around its virtual environment. Yet, many people play in the same physical room—in fact, it was originally created as a game for local play. This means that the game’s boundaries can be expanded to include people’s facial expressions, body language, and even friends’ prior knowledge of one another.

Both Among Us and Realish Friends isolate players with the “good” roles—crewmates and truthers, respectively—by design, creating an “every man for himself” dynamic. In contrast, while Among Us’ imposters also predominantly experience the aforementioned dynamic, Realish Friends’ evokes a greater fellowship aesthetic amongst liars. Due to its in person mode of play, Realish Friends successfully unites the “bad” roles, where the outcome of the collective matters more than their individual fate in the game.

By offering few mechanics to verify information, Among Us and Realish Friends force their “good” players to rely on guesswork, fleeting memory, and gut instinct. This floods them with doubt, turning solid logic into suspicion, eroding trust, and pushing players toward self-destruction.

For instance, when playing Among Us, we reached a round with four players: lagunita, soosoox, Paperprime, and Leo. In the screenshots above, Leo suddenly begins accusing soosoox of being an imposter without providing any evidence or reasoning. When lagunita asks Leo to explain their accusation, Leo simply continues to insist “it’s soosoox” without offering any substantiation. This baseless accusation immediately makes lagunita and Paperprime wary of Leo’s motives—why would someone make such strong accusations without evidence unless they were an imposter trying to eliminate an innocent crewmate? Due to their growing suspicion of Leo, lagunita and Paperprime refuse to vote, resulting in no ejection that round.

In the next round, soosoox kills Paperprime, and lagunita walks in on the murder just as soosoox vents away. However, in the speed and confusion of the moment, and still influenced by their earlier distrust of Leo from the previous round’s suspicious behavior, lagunita misremembers what they saw.

In this set of screenshots, we see lagunita become convinced it was Leo who they saw. Leo tries to correct lagunita, but soosoox cleverly exploits the situation by reinforcing lagunita’s bias against Leo, reminding everyone of Leo’s earlier unfounded accusations. Lagunita, down to the round where their votes will determine the outcome of the game, is now fully immersed in the “every man for himself” dynamic. Lagunita couldn’t trust either of them, trusting his own flawed memory instead, voting out Leo. Lagunita’s eyes deceived them, but so did the game’s structure.

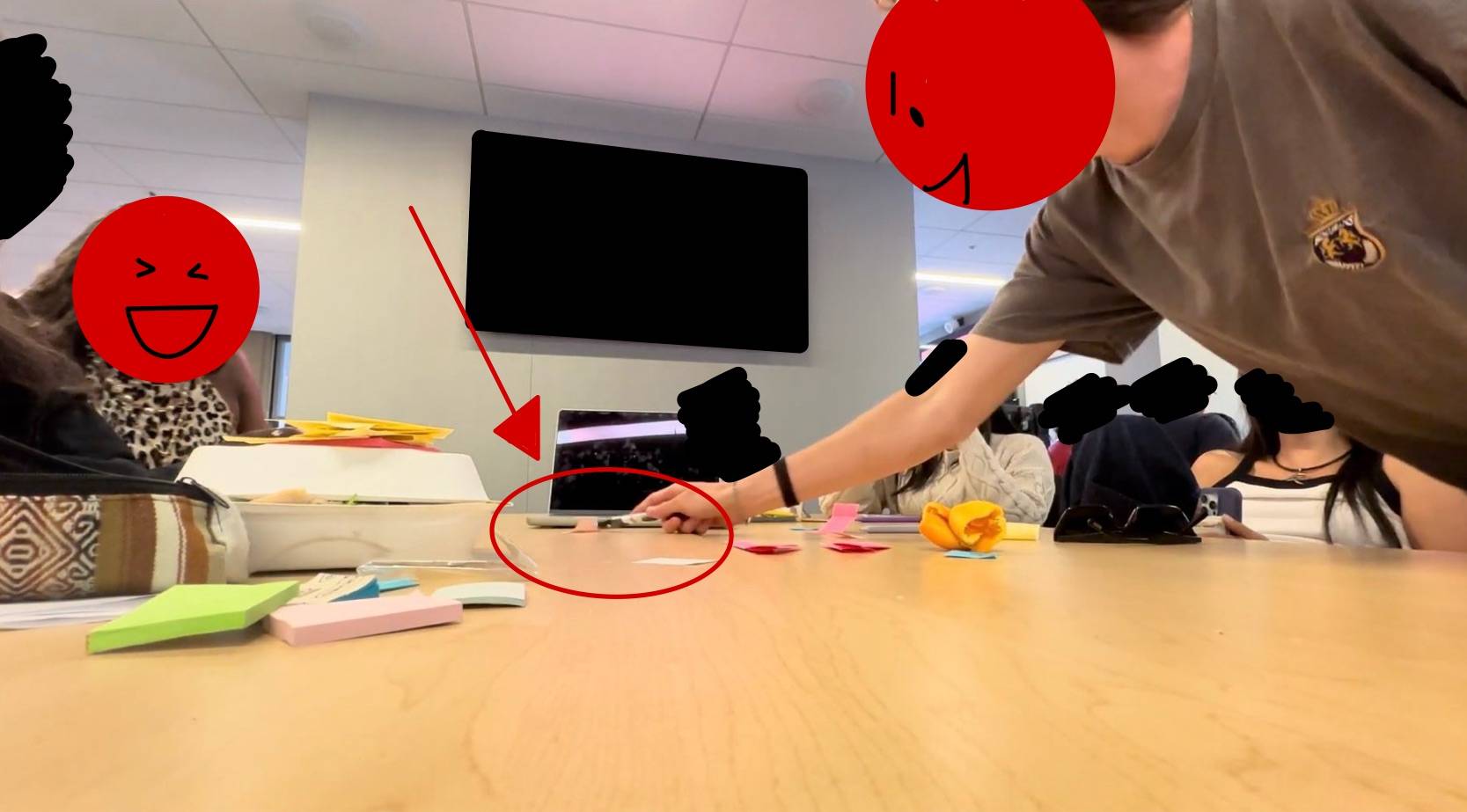

Similarly, in my team’s game, Realish Friends, we reached a final round with three players: two truthers and one liar. Though both truthers, Cody and Grace, had correctly identified the liar before discussion began, paranoia took over. Cody relied heavily on logic, insisting he couldn’t possibly be the liar. Grace, with no way to verify his reasoning, interpreted his certainty as manipulation. While she attempted to focus on narrative details from the storytelling round, Cody’s persistent logical arguments made him appear defensive and controlling. Meanwhile, the liar, Mena, took advantage of the situation by sitting back quietly and watching the truthers’ self-destructive dynamic unfold in her favor. As Grace’s suspicion grew, when voting time came, Grace stated “Cody, right? Cool,” implying her vote for him. Cody, driven by spite and self-preservation, abandoned his earlier suspicion of the actual liar and pointed at Grace’s name tag (pictured above), implying he would vote for her in return. In the end, the truthers’ inability to trust each other led them to vote against one another, handing the victory to the very liar they had both initially suspected.

These moments illustrate how Among Us and Realish Friends weaponize uncertainty. While the games are framed as a team-based deduction challenge, crewmates and truthers are rarely able to function as a true team. The mechanics offer no persistent tools for memory, behavior/play tracking, and no way to build long-term trust. As a result, the games create a deep fragility in the crewmate/truther experience, for they can solely rely on instinct, perception, and social read/persuasion. Unlike games like Werewolf or Secret Hitler, which provide players with voting records or structured turns that allow information to accumulate and trust to build, Among Us and Realish Friends provide no scaffolding for trust to form. Each round is a fresh paranoia spiral. While these mechanics form fast, choatic, and emotionally volatile dynamics that feed into the games’ challenge aesthetic that its players love, crewmates/truthers are still structurally disadvantaged. The game rewards imposters/liars like soosoox and Mena who can exploit confusion or distrust and punish crewmates/truthers like lagunita, Cody, and Grace who misremember or hesitate. One possible design intervention for Among Us could be to introduce optional memory aids, such as a replay of the last 5 seconds of gameplay. This would be especially helpful since players often rush to hit the “report dead body” button out of fear of being killed, which limits their ability to process who was present at the scene. This would preserve the chaotic atmosphere while giving crewmates something to anchor their reasoning and a mechanism to build trust with one another. Another possible design intervention for Realish Friends could be the introduction of a personal suspicion tracker. This would allow players to maintain notes throughout the rounds, recording who they suspect and why. This feature could help truthers improve their reasoning and memory during gameplay. More importantly, it could enhance credibility, providing a mechanism for trust-building amongst truthers. During high-stakes final rounds, when truthers must convince each other of their innocence, they could reference their consistent line of reasoning in their notes to strengthen their arguments. This would show that their suspicions developed through careful observation and logic rather than impulse or deceit.

Now, unlike Among Us, where deception is largely a solitary strategy with superficial alliances, Realish Friends uses mechanics that unite liars and utilizes its platform/mode of play to maintain eliminated players’ physical and emotional presence. This encourages liars to protect one another, transforming deception from an individual pursuit into a collaborative act that strengthens their fellowship.

Yes, in Among Us, imposters can and do work together—they double-kill, alibi for one another, and coordinate sabotage. Nevertheless, their alliance remains fragile. The virtual platform limits communication, and once a player is eliminated, they’re removed from the game’s magic circle and cut off from all discussion that affects the game’s outcome. In fear of reduced agency, self-preservation becomes the priority. Further, the virtual environment separates the player from the person, making it easier to betray a fellow imposter if it means surviving another round. Altogether, these dynamics lead to a primary aesthetic of competition.

Realish Friends flips this dynamic through two key mechanics: in-person play and upfront role knowledge amongst liars. Since the game is played in person, eliminated players remain physically present. Rather than being mere spectators outside the magic circle, their physical presence, reactions, and emotional engagement continues to permeate the game’s boundaries. This presence softens the sting of elimination and keeps liars invested in the outcome, even if they’re no longer active players. Moreover, their physical presence changes how liars relate to one another. During playtesting, one liar noted,

“I did like knowing who the other liar was also because I feel like it made it easier to like know to like derail the conversation when like people were sussing her out or like to vote like whoever people would vote for instead of her.”

This demonstrates how Realish Friends’ mechanics foster mutual protection between liars, creating fellowship on top of competition. The game creates a truly shared victory experience. Even if you’re caught early as a liar, you remain an integral part of the win. You witnessed it unfold, supported your partner, and saw your earlier deceptions pay off. In Among Us, however, being eliminated as an imposter disconnects you from your team. You’re excluded from the conversation and tension. When your team wins, it feels distant, like watching others finish what you started and failed to see through.