Game Link: https://simrant.itch.io/p2-slash

Overview

This summer, I got obsessed with slasher films. SImps (the Stanford Improvisors) does slasher shows every year, and this year was my second time directing it. All this to say – I love a slasher, and I think about them constantly. Though not a classic dystopia, the thing that has always fascinated me about slashers is the male-centric obsession with violence against women. Killers are driven by their innate desire to torture women, with male deaths often being consequential of revenge against women. With my game, I wanted to explore the dystopic (startingly close to reality) “world” of a slasher, with an actually female-centric perspective.

Slash is a time-loop (ish) based interactive fiction about trying to uncover a killer. With all the genre trappings of iconic slasher flicks of the 80’s and 90’s, this game is set around a small cast of teens and townspeople who are victims of the slasher. Each game loop is a day you play as one of the three main female characters, until the house party, where you get slashed. The loop finally ends when you discover the slasher’s identity and get your revenge.

History Versions of the Game

When I first sketched this game out on cards, I drew heavily from the Scream movies for inspiration. My two biggest worries with my game concept was scoping my game well for this assignment (not making it ridiculously long), and keeping the player intrigued through a repetitive narrative.

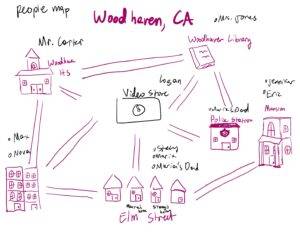

Along with cards, I also started with a map of the town, with the set of 6 locations in town. When the player woke up as a new character, I would change out the set of available locations. In my first playtests, players noted that they liked the map visual and the tone of the game. While I eventually got rid of the map due to it not making sense with the direction my game took, I did learn that playtesters enjoyed a sense of knowing where their character physically was.

The most valuable thing I learned from playtesters in the early stages of the game was making all choices valuable in some way. When playtesting with Zoe and Anna(both college-aged female 377g students), both of them let out a frustrated “Aww” when they found they missed an interaction they perceived as more interesting by choosing “Apply Makeup” instead of “Check Phone.” They reflected that they wished both choices had given equally interesting outcomes, instead of one being a shortcut to the next significant story beat.

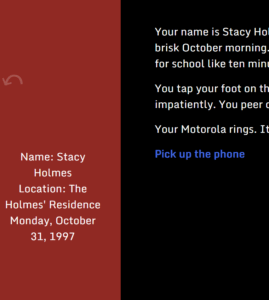

In later playtests, something I changed in my approach was explaining the premise. I wanted to see if players would understand the loops, or if the nature of the story was confusing. Playtesters Houston(college-age female 377g student) and Manas(college-age student, avid gamer) both indicated that they got a little confused about if you switched bodies and it was a new day, or if there was a time loop aspect to the game. In Manas’s playtest, when he started playing as the second character, Maria, he said “Wait, I can see Stacy? Am I not Stacy?.” In his speed, he had nearly skipped this information and got lost as a result. This reflected that it could be hard to remember which of the characters they were currently playing as without a clear reference, which is something Amy also brought up in her playtest.

As I transitioned to the digital version of the game, this led me to later develop the sidebar where the name of the character is always viewable, along with the name of the current location to make up for the missing map feature, and to help players remember where they are.

After this, the main changes I made to the game were based on the story structure and loop. My next playtest with Haven (college-age female 377g student ) and Daania (college-age female student, casual gamer), along with my earlier playtests, reflected that players wanted to have a sense of being able to fight back somehow. When Haven played the game, she went “Oh, no, no, don’t go into the basement” When Stacy went to get a drink. She commented that because the game relies on tropes, the player can get a sense of when they are being trapped. This led to two developments in the game – making one or two “fake-outs” where there appears to be a risk of death that never materializes to add more tension, and building out the fight scenes more. Earlier playtesters (Anna and Manas) and Daania also indicated they wanted to prolong the death scenes because they felt very sudden. To me, this meant that the deaths were reading as a little anticlimactic, so I decided to add more interactivity.

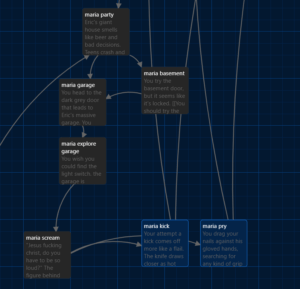

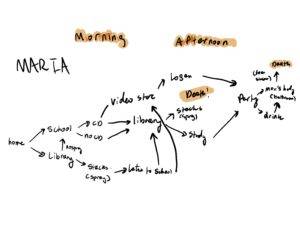

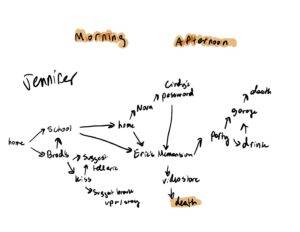

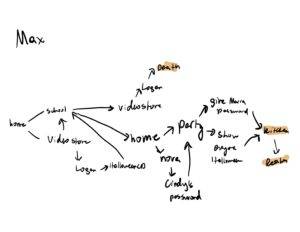

Throughout this process, I was also evolving how the game was structured. Originally, it was going to be a real looping structure, and the condition to win would only be activated if you went to the right routes. However, during development, playtesters pointed out that repeating the exact same choices was unrewarding – they wanted a little bit of variation and a sense of control. I thought the best solution would be expanding the number of choices in each loop, so I modeled the stories like this:

But, after playtesting with Amy and asking her about scoping the game appropriately, I saw that this model would be time-consuming and way too long in its final form since the end was not definite. I then thought about just removing some of the branches from the loop, but when I playtested with Lana (23 year old freelance artist, casual gamer), she said that it felt like it was hard to remember where you had gone and she wasn’t sure what the right direction was. This led me to my final structure, with a much simpler layout.

This new structure focused on two main branching paths. Players can play each path on any loop, but the game now pushes them slightly towards the one they haven’t done. This way, players can have a sense of where they have been before and where they “need” to go next. Additionally, at the end of the second playthrough of Jennifer’s loop, I set a new condition to reveal a key piece of information and send the player to the final loop of the game, where the player can kill the slasher using what they learned.

The final major change I made came from feedback from Lana and Daania when they playtested the game a second time. When Lana reached the final confrontation, she noticed a bug where the link to the next passage was missing. I saw that it was because she hadn’t fulfilled a condition of finding Maria’s pepper spray, and she asked “Oh! Do I lose now?”. This question surprised me, since I hadn’t really thought about having a losing condition.

I realized that I was missing a sense of consequence in the game – it was very story-driven, so much that I think I lost a little of the game aspect in it. I ended up adding two new conditions, so if players haven’t found key items, it sends them back to the loop where they need to find it so that they can kill the killer. While this isn’t a real “lose” condition, I wanted to have some way for the choices the player made in their loops to mean something, but give them an easy opportunity to fix it and complete the game.

Reflection

I both really loved and got really frustrated working on this game. It felt like a passion project, as I got invested in the characters and the story and the message, but I also felt the struggle of trying to achieve the vision in reality. I learned a lot about making interactive fictions, not just in the sense of learning how to use Twine and how to map out the story, but in the sense of the challenges of telling a story in this format.

One of my greatest challenges was scoping appropriately, since I wanted to make sure I wasn’t going to make you guys play a ridiculously long game (and I really hope it’s not, I timed my last playtests to make sure it was within the ½ hour limit but you never know). It is so exciting to make a game like this that you can go overboard, which is definitely what I did for a large part of the process. I learned from my hubris, however, and after feedback and playtesting I scaled down massively from my original concept. I also made the mistake of writing directly in Twine – I wish I had sketched it all out on cards first, since I liked how little I could write on the cards. In Twine, I would often lengthen passages and get way too wordy because I had no upper bound, which resulted in me needing to cut a lot of content to fit the scope.

The next time I make an interactive fiction game (or continue to work on this one), I think I would approach planning the game differently. I would try writing the whole thing on physical cards first, and understanding the story I’m telling before thinking about the ideals of my vision for the game. I think this would help me scale better and understand what is actually important to the story before moving it to the digital side.

Hi Simran! I’m one of your peer reviewers~

I love how your story is structured and written, and I was very emotionally invested in your story (and the survival of the characters). The amount of choices in this game feels just right, not too many or too few.

Some things you can work on: What exactly do you want me to question in this game (educational value)? Is there one? I enjoyed the game, but I’m not sure what could be the topic. It is also longer than I expected. Some may feel it is too long to read (I feel that it’s hard to provide so much details with shorter stories though)?