Team 1: Asher Hensley, Butch Nasser, Haven Whitney

Overview

EndangerEd is a multiplayer board game intended for 2-6 players ages 13+. Players play as animal conservationists with a specific endangered animal they individually wish to preserve. However, due to natural events, lacking finances, and players’ conflicting desires for favorable habitats that could possibly suit other species, players may find conservation much more difficult—and competitive—than originally expected. EndangerEd hopes to achieve the outcome of changing players’ attitude towards animal conservation by highlighting how mass legislature intended to protect one animal could easily harm another sharing that habitat. We chose this topic because we believed that the general public does not have an accurate understanding of the processes and difficulties involved with conservation and preserving our ecological systems and the animals within.

In approaching these topics, we believe our game perfectly encapsulates fun through challenge, discovery, and fellowship; players must overcome a set of obstacles from lack of funding, random event cards, and other players’ choices that result in feelings of triumph after being overcome. As they play, they reveal the map’s tiles, and learn of new dangers or boons; they also can find solace in working towards a similar goal as other players, but when there’s limited favorable tiles remaining, they may enter into a cutthroat competitive experience to emphasize how endangered animals—and those protecting them—often compete to achieve their goals.

We wanted to create a game with significant replayability, the ability to offer differing social dynamics based on each player’s decisions and playstyles, and a perfect place for players to show their competitive drive—while also learning about competition in the field of conservation. We did this by having animals exist on tiles with designated habitat types and habitat intensity values that players could manipulate in their favor as they played. For most actions, we wanted it such that changes in their favor would typically mean making it more difficult for other players to achieve a similar goal—allowing players to experience firsthand how the goal of preserving a single animal will lead to competitive conflicts. Additionally, we wanted players to learn the financial difficulties of research or conservation by making every action cost money, and forcing players to experience negative events in order to gain money—one’s financial gain would often be associated with upsetting the current board state, and the other players’ investments into the board.

After playing, players would be able to analyze the interactions each player made to assist their species, and recognize that it often came at a cost. But would players band together towards their similar goal, or preserve their own resources and investments to best protect their designated species? Find out as you play EndangerED!

Rules

The Ecosystem Needs You!

Animal conservation is tough work! Play as a group of animal conservationists each working to save your own endangered species. But watch out: saving one species may mean endangering another! In this game for 2-6 players, find out firsthand how competition between animals extends beyond animals upwards to the efforts to protect them as well. Manage your funding, explore, migrate, introduce, and terraform your way to preserve your animal! Embrace your inner competitive nature in EndangerED!

Setting Up

- All players start with $5,000 in grant funding. Each player should pick a random animal card from the animal deck. Players should reveal their animals to each other.

- Place the center habitat tile in the center of the gameboard (this tile represents Desert, Water, and Forest tiles at once). Randomly place all other habitat tiles with habitat type facing down into the remaining spaces on the board.

- Each animal exists in the wild before we researchers come along, so players place one token of their animal type on any tile. Once all players have placed an animal, flip all occupied habitat tiles.

Your Animal Card

- An animal card represents the animal species you are trying to save. Each animal has an ideal habitat (forest, desert, or water) and ideal habitat intensity value for that tile (1, 2, or 3).

- For example, the American Goshawk prefers varies forest conditions with open canopies and forest openings, so its ideal intensity value is 1. However, the Mexican Spotted Owl prefers thick canopies and undergrowth, so its ideal intensity value is 3.

- Note: The center tile of the gameboard can fit any habitat!

Round 1: Research

- In the first round, all players can choose one unexplored tile to do field study in. Pick a tile adjacent to any explored tile and flip it over to reveal the habitat and value markers.

Proceeding Rounds:

In the proceeding rounds, our researchers find themselves competing against one another and time. At the beginning of each round the starting player draws a natural event card that could have effects ranging from benign to disastrous to the environment

- Enact whatever the card states. If it says the value of a tile should change, use the 1, 2, or 3 tokens and place them on the corresponding tile(s) to represent the change. Do the same for marking dangerous tiles with skull tokens.

- The starting player of a round rotates clockwise with each round.

- There are 7 rounds total, including the research round. Each round, players will take turns to perform their actions.

Player Actions:

Time is limited! Researchers can either spend their time (represented as their turn) to receive additional funding, or do two of the following actions:

- Additional field study ($1,000): reveal one unexplored tile adjacent (surrounding) to one of your animals.

- Migration ($1,000): Choose one of your own animals to move to an unoccupied tile adjacent from its current position.

- Species Introduction ($2,000): Add another of your own animal to any unoccupied, explored tile.

- Terraform ($1,000): Increase or decrease a tile’s value by 1. Tile must be occupied by your own animal and cannot have a value less than 1 or greater than 3.

- Sanctuary ($5,000): Create an animal sanctuary on a tile. Any dangerous tokens are removed, and it is immune to all future event cards. That tile holds all ideal intensity values (1, 2, and 3).

Funding

- Players can earn more funding by drawing a funding card, but these can have unexpected consequences! Each card gives the player $2,500 unless otherwise stated. When drawn, perform the action on the card immediately.

Dangerous Tokens

- A tile with a dangerous token or marking on the card contains valuable resources companies wish to exploit at the expense of wildlife.

- Some funding or natural event cards may destroy dangerous tiles. Be careful if an animal is on the tile, as it will die out and be destroyed!

- For events, adjacent tiles are any tiles located on or surrounding a certain tile.

Scoring

- After 7 rounds, calculate the score. Players receive 4 points for every animal in the correct habitat and correct value for their animal, and 2 points for every animal in the correct habitat. The player with the most points wins!

- If a player at any point has zero animals on the board, their animal has gone extinct and they lose.

Game Bits

Each Copy of EndangerEd contains:

- 26 funding event cards

- 19 natural event cards

- 14 danger tokens

- 30 values tokens (10x 1, 2, and 3)

- 45 habitat tiles (Forest, Desert, Water, Center, including 20 extra tiles)

- 30 animal tokens (6x 5 animals)

- 1 game board

Assessment Goals

EndangerED intends to inform players about the difficulties that conservationists face. The main hurdles showcased in our game through play include working against time, corporations, and fellow conservationists to preserve a species. Resources are limited and often require competing against other conservationists. We showcased this limitation by emphasizing the small differences in a habitat that could make it unsuitable for one species but habitable for another. A common misconception we wanted to correct about the five major biomes is the belief that an animal living in a biome (i.e. a forest) can live in any environment within that biome. We accomplished this by making 3 different levels for each biome that suited different animals and describing them on our animals’ cards. Habitable land was also made scarce by corporations wanting to make the land unusable to obtain natural resources.

We also wanted to give players the opportunity to learn more about different endangered species by providing facts about the different animals that could be played. To evaluate our players’ learning, we asked them on a scale of 1-5 what they knew about animal conservation before and after. For our final playtest, only two of our respondents changed their answers: from a 1 to a 2.5 and a 2 to a 3 respectively. We also asked them to list challenges to conversation that they observed through our game. They responded:

- Conservation is expensive (everything relies on money)

- Competition with other animals and companies is frustrating

- Environmentalists must compete sometimes

- There simply aren’t enough non-threatened habitats for ecosystems

- Nuance in habitat intensity beyond “just in natural habitat”

- It is hard to migrate/relocate an animal community

- Funding is necessary to take political action

- Bigger picture notions of conservation “actions” such as research and exploration for suitable habitats

These were all points we hoped to get across through play, so we would mark this as a success! Although players didn’t quite remember the facts about the animals we put on their cards, our playtesters said that the more they played, the more attention they paid to the facts on the cards. Although the cards have too much information for one to digest immediately, repeated exposure to the cards could positively impact on the retention of facts presented.

Testing and Iteration History

We believe our game experience is not significantly impacted by the gender identity of our players. Given this, and that we did not specifically request playtesters to disclose their pronouns, our demographics listed for each playtest are limited to the academic year of the players.

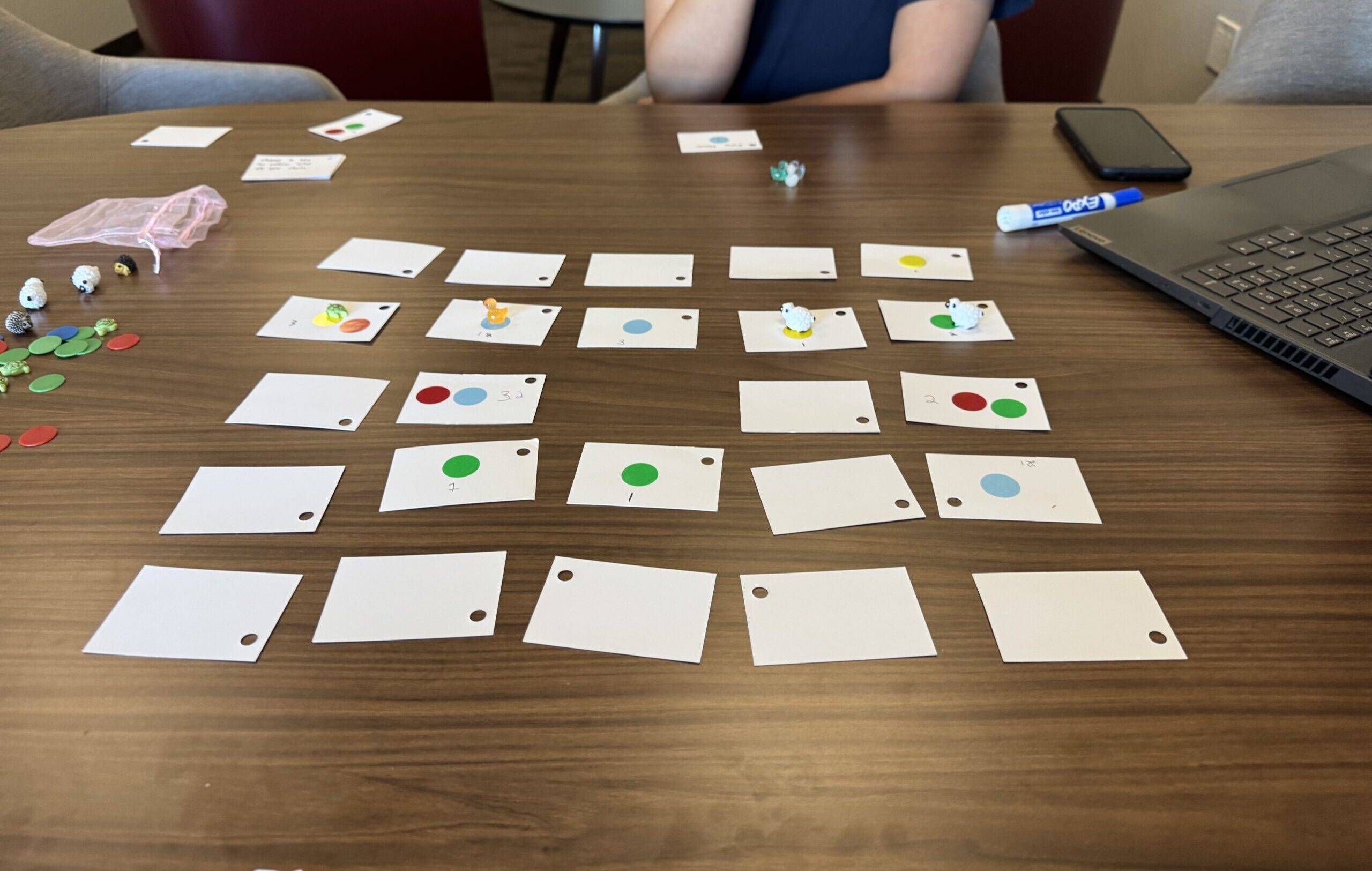

First playtest

Our first playtest of EndangerED involved a square map of habitat tiles. Our group was composed of 4 players, all of which were undergraduates. Every player began with $20,000 in grant funding that they could spend as they chose on one action per turn. The actions: move an existing animal one tile to an adjacent tile for $1,000, introduce a new animal of their species to the board at any tile for $2,000, or terraform a tile to increase/decrease its value by one (to a minimum of 1 or maximum of 3). Each round, a natural event card is drawn by the first player. This could impact the entire board, such as by raising the water levels of all water habitat tiles by one, or creating new dangerous tokens on previously safe tiles.

Immediately, we noticed a desire for collaboration within some players at odds with a more competitive mindset in others. One player, for example, said, “I vote we collaborate” after the rules were explained. Many early wins for fellow players were celebrated among the group, as animals migrated across the board to their ideal habitats. However, due to the limitations of the actions players could perform (with players asking on more than one occasion if there was a way to perform additional actions beyond the three we introduced), one player expressed that they cooperated with others only because they couldn’t do anything else. Several players also expressed that there was no real financial risk or reason to come into conflict with others, as the starting budget was too high to ever pose a threat, even when taking the most expensive actions every turn. The event cards were also not a large component of gameplay, as only 3 were played during the game. Players found this too infrequent to be of much notice or to cause an impact on their strategy.

It’s worth noting that this sense of cooperation was not unanimous, with one player mentioning they didn’t “care about ecological diversity; [they] want to win the game.” This would be a common thread throughout our future playtests, as the more competitive aspect of animal conservation was explored more deeply.

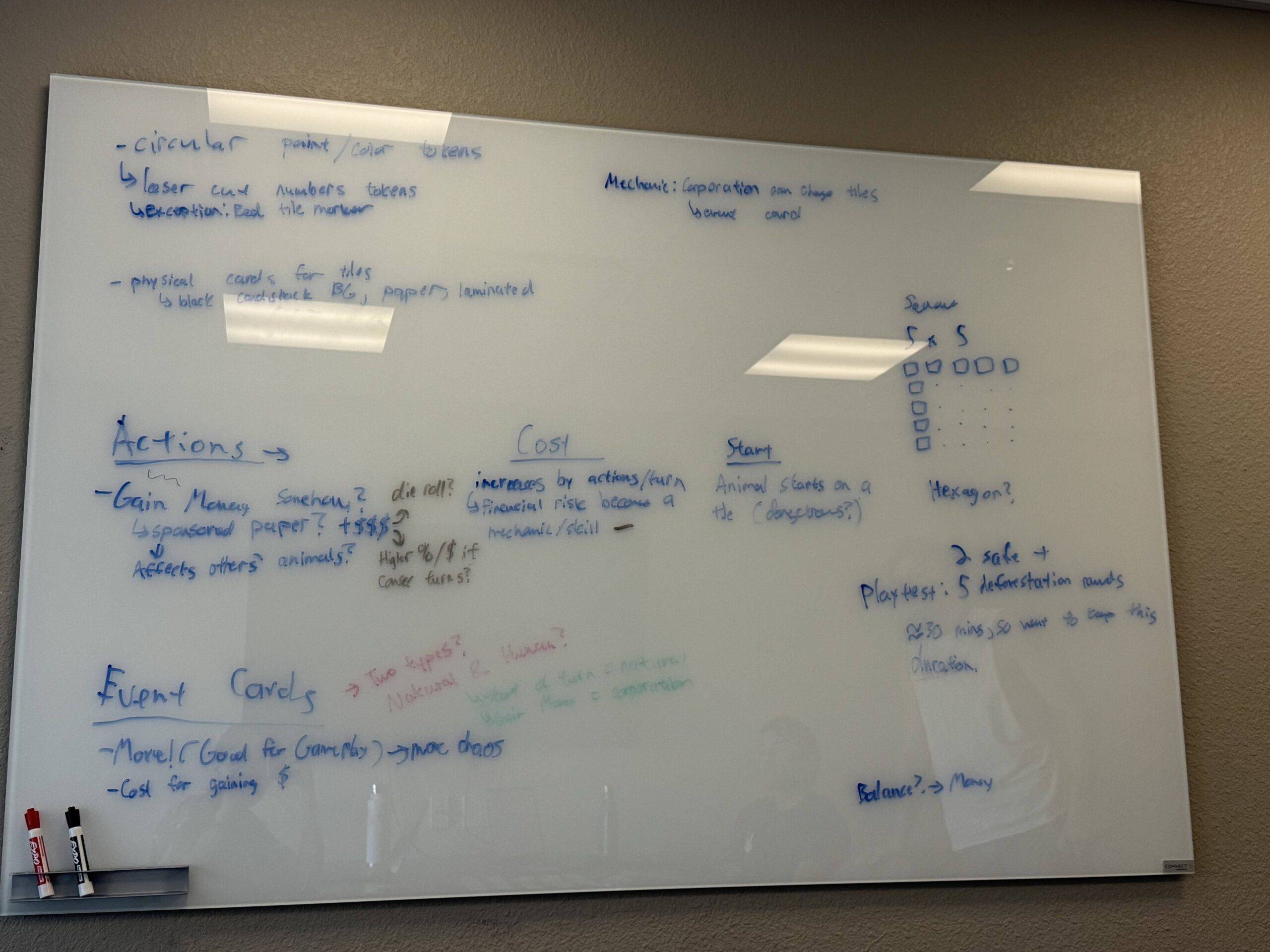

To address this early feedback, we rebalanced both the budget for each player as well as the price of each action to introduce more stakes and incentivize players to strategize. We also added additional actions for players to perform, including the ability to gain additional funding by drawing a new event card.

Weekend playtest

Our next playtest saw immediate positive results in engagement through the changes we implemented. We had three total players, all undergraduate or first-year graduate students. The addition of funding cards—a specific type of event card played when a player chooses to gain money—created a livelier and more competitive atmosphere, with several players yelling over the table at each other good-naturedly when one chose to draw a funding card. Because these choices could negatively impact other players, it introduced more of the competitive aspect we hoped to teach. These were played fairly frequently due to the reduction of the starting funding for each player to only $5,000.

A few pain points were noticed at this stage; for one, players mentioned a lack of variety in the event cards. While some were changed the board dramatically, others did nothing or weren’t particularly engaging. The theme of player choice in actions came up again, with some players noting they felt they didn’t have many options available to them with only a few rounds to move and place animals.

There was much discussion at this point about the advantages and disadvantages of either increasing the total number of rounds in the game or changing the action economy to address this feedback. While both changes had merit, we ultimately decided to increase the number of actions from one to two per turn. We felt this would give players more ways to spend their funding without unnecessarily dragging out the game. From our own experience in playing games, we hypothesized that feeling more powerful would increase fun and engagement more than just forcing players to play longer before they receive gratification. Further playtests agreed with this approach.

In addition to changing the action economy, we increased the quantity and variety of event cards to improve fairness.

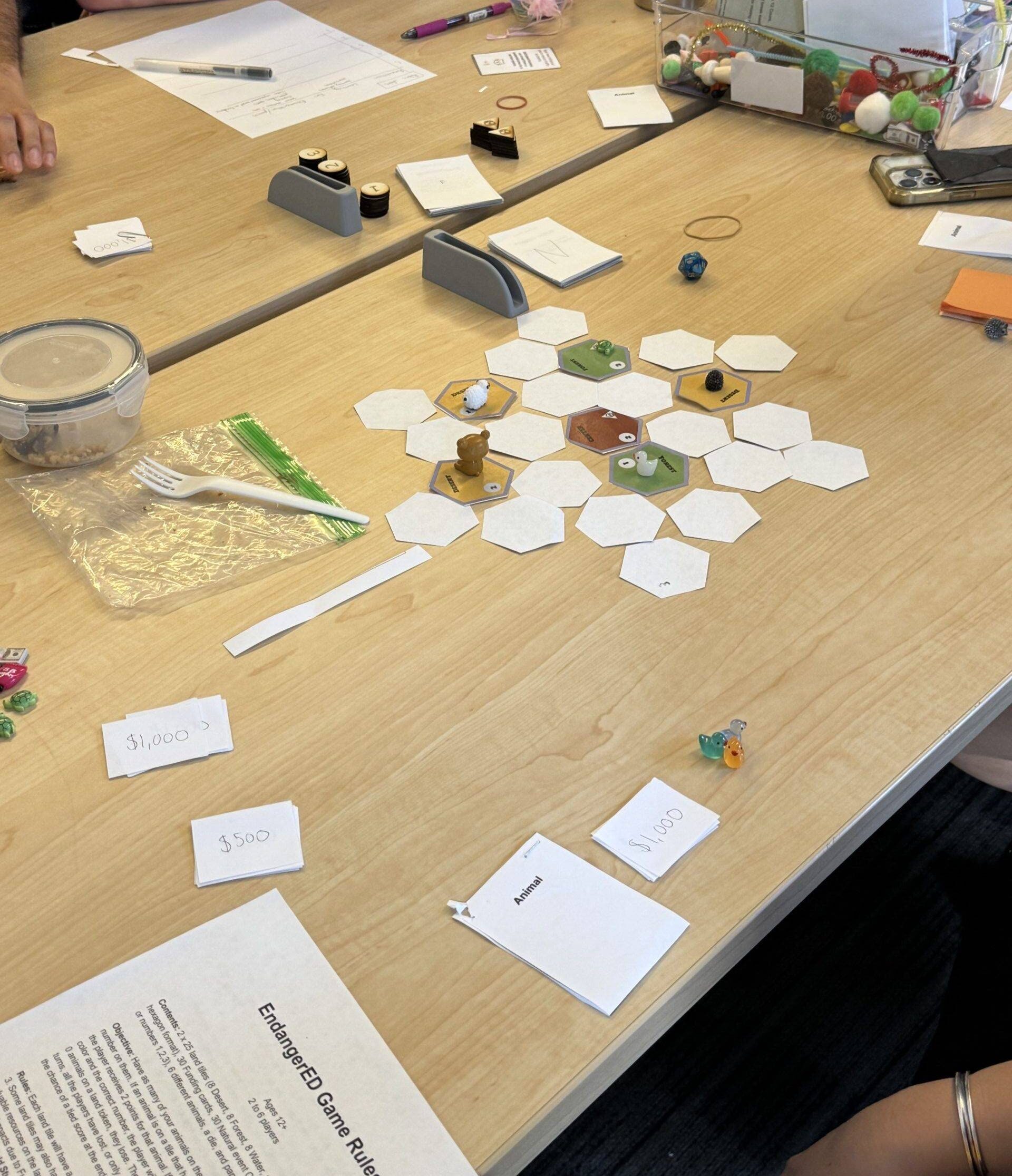

We also, in the interest of exploring other approaches to game layout design, created a version of the game using hexagonal board tiles to determine if it created more interesting spatial interactions between players. This choice was partially inspired by the Catan game board, but also due to decreased tile distance players would be able to migrate to reach specific tiles, which would increase competition.

Second In-Class playtest

Our next playtest introduced our first writeup of the rules system, with five undergraduate players. Right away, we noticed players found the written rules more confusing than when presented out loud by a moderator. This was an excellent learning moment for our team, as we were able to quickly identify the elements of the game that were difficult to understand from an outsider’s perspective. We took note of all confusion during this process and clarified it in our following rules for the final playtest.

At this point, fidelity became a detractor in communicating the idea and experience of the game. Players noted difficulty in flipping our hexagonal tiles without disrupting them, as they were made of paper and not sturdier material.

Furthermore, the paragraph format of the rules didn’t express the salient points most effectively. Players noted being unable to find important information about their animals or on event cards without guidance. With this feedback, we took note in preparation for our final playtest.

Final playtest

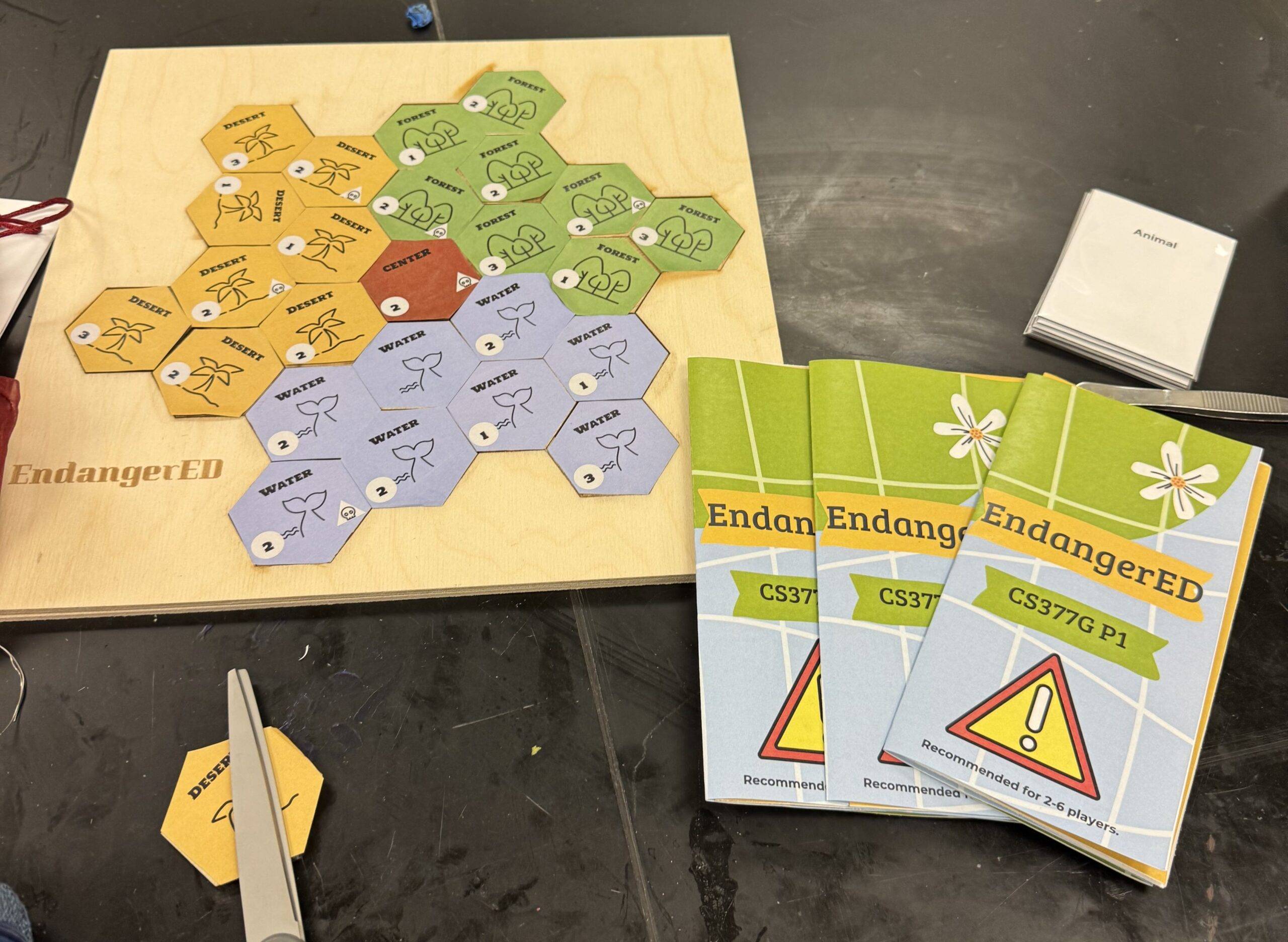

We decided to address both of these issues, as well as work towards expanding on the theming and visual quality of the game, by creating higher fidelity prototypes. These took the form of a new wooden game board and tiles, wooden tokens to represent dangerous habitat tiles and values, card sleeves and printed cards for animals, funding event cards, and natural event cards, and finally a visual trifold pamphlet to explain the premise of the game and its rules.

We aimed for a clearer objective so players could strategize more effectively. This seemed to work—the rate of play increased significantly faster than the last playtest with these clarifications. Our final playtest had six undergraduate players, all of whom were impressed by the fidelity of our newest prototype. Balancing of the mechanics was noticeably better than in previous iterations, and from an observer’s perspective the players seemed engaged in the gameplay.

Interestingly, we experienced the most resistance to our learning goals in this playtest. This group of players expressed experiencing much higher sentiments of competition when asked than in previous iterations of the game. Our new event cards truly pit players against each other; there were several moments in gameplay where players entered negotiation to avoid the loss of their own animals, or in order to gain access to a more ideal habitat. An example of this can be found at 23:58, when one player asks another not to “hurt them” within the game when they draw a funding card, to which the other reassures them that they won’t.

In one such case, a funding card was drawn that asked a cumulative ransom of $8,000 to avoid the destruction of all revealed dangerous tiles on the board. Only one player of our six playtesters, however, had an animal on such a tile, and none of the other players wished to spend their limited resources to aid them. This resulted in the single threatened player pleading with their fellow conservationists to no avail, and the tiles were destroyed. This can be seen starting at 43:40 within the final playtest video.

We felt that this moment truly encapsulated many of the issues in animal conservation we wished to bring awareness to with our game. However, players seemed surprised by the amount of competition, with some even expressing doubt it was accurate. After review, we feel that this was a failure on our part to set the expectations of the game rather than an incorrect direction in the playstyle. As previously mentioned in our assessment goals, one takeaway we wanted players to understand was the inherent conflict between some animal conservation efforts. When asked, many players mentioned that they felt it was a prominent part of the gameplay, showing that they did understand our point, even if they didn’t necessarily know to expect it from the outset. To this end, we modified the rules from the final playtest to the print and play to be more explicit on the competitive angle of the game. Were we to continue improving upon the game, we would apply playtester feedback to add more Event Cards to further increase replayability, and modify our tiles with small semicircle indentations on edges, to make them easier to pick up/flip over.

Print And Play

Overall, we enjoyed crafting EndangerED, and hope you enjoy playing it as well!