Doki Doki Literature Club! (DDLC) is a 2017 visual novel game created by Team Salvato for Linux, macOS, and Windows. This seemingly “dating simulator”-esque game is rated MA15+ and is unsuitable for children due to depictions of graphic violence and self-harm, often delving into more mature topics. However, for those that like twists and tensions in an inversely cute anime setting, this game is surely one to remember.

Central Argument

Doki Doki Literature Club (DDLC) appears to be a stereotypical dating simulator on the outside, with three cute girls you can “choose” to pursue. However, this game embeds a series of disturbing reveals within its narrative that challenges the player’s assumptions, emotions, and intentions. DDLC successfully subverts from the typical “male gaze” within anime and games and uses the illusion of choice to embed agency in its narrative, in which a player critiquing as a feminist must identify and analyze the system of power within the game to rethink their relationship with fiction and intentions as a player. This push and pull of player control vs. character control are what Shira Chess in “Play like a Feminist” speaks of as a “primary drive” for women game players for certain games, to which DDLC is able to appeal to the aesthetic of expression and narrative but sacrifices full character agency as a result, leading to the game falling short of its full potential as a feminist game.

Subversion of Anime and Visual Novel Tropes

DDLC reinforces the narrative aesthetic as a horror parody of typical visual novels and the “cute girls doing cute things” trope, creating a tension-filled environment with mechanics like contrasting backstories and appearances for the girls, disturbing visual glitches on the girls’ faces, and vulgar language and exchanges that don’t fit the expected “feminine” behavior.

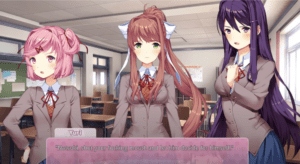

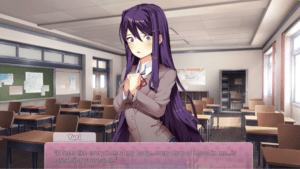

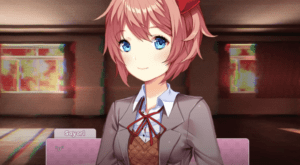

The subversion from traditional dating sim tropes is highlighted by the stark contrast between the game’s art and initial storyline. The player is able to choose between three girls to pursue that all have distinct personalities representing common anime/visual novel tropes – Sayori is your childhood friend with a crush on you, Yuri is mature yet quiet and shy, and Natsuki follows the “tsundere” trope that is snarky on the outside but a sweetheart inside – which all contribute to the “male gaze” and expectations for these games. However, these characters begin to show signs outside the “normal”, with contrasting backstories and “real” problems that are hidden in traditional visual novels to focus more on the romance – Sayori facing severe depression, Yuri’s self-harm, and Natsuki’s troubled relationship with her father. The art and dialogue take a turn as the narrative progresses into horror as well, with horrifying and glitchy faces replacing their usual sprites and unfeminine dialogue consisting of vulgar language and offensive banter (as seen below between Yuri and Natsuki). Thus, since the game followed traditional dating simulator tropes so tightly in the beginning, DDLC is able to create a dynamic of tension and alarm whenever something isn’t in place, forcing the player to rethink their expectations for the game, the women within it, and the player role in order to make sense of the story and predict what happens next.

Not only does this dynamic of uncertainty and alertness appeal to the narrative aesthetic – it also intertwines feminist theories like pluralism and post-modern feminism which critiques a universal view of how women should behave. According to Chess’s logic, this would mean that DDLC provides a good feminist story in that it relays narratives that “surpass the expectations we tend to have of those ushered in to and for patriarchal audiences”. Additionally, it also avoids the issue of being “climax-centric” due to its structure following not a straightforward climax but rather a series of disturbing reveals.

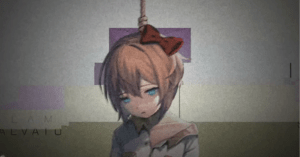

My concern, however, is the lack of direction the player is faced with when they become wary of the women in the game which they are supposed to pursue – this is an issue that contrasts with Chess’s claim that a good feminist game should have potential for “empathy-building”. With mechanics expressing the girls’ dark side to the extremes, with Sayori committing suicide after only subtle mentions of her depression and Yuri’s graphic stabbing, we realize that this was all a result of Monika’s amplification of the other girls’ harmful tendencies to get the protagonist to love her – none of these scenarios are realistic enough to relate with and feel empathetic to. These extreme mechanics instead create a dynamic of fear and aversion. Even if the players felt a drop of empathy for the girls’ backstories, the final realization that these events were done out of love for the main protagonist is anti-feminist to its core.

The Illusion of Choice and Power of Agency

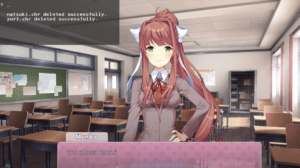

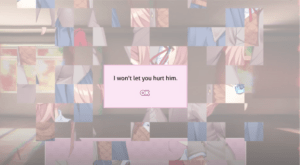

Initially, the game presents typical choices for which story the player would like to experience. As the game progresses, it becomes increasingly apparent that the choices are meaningless and there is only an illusion of choice, in which agency is transferred from the player over to the characters. This was illustrated through mechanics such as only allowing one clickable option despite displaying many (forcing the player to choose Yuri’s storyline first), obstructing the view of the dialogue boxes by putting character sprites in front of them once they’ve gained agency becoming “aware”, not allowing the player to exit, and even taking communication from dialogue boxes to speech at the end with Monika after she addresses the player not as the protagonist, but the person behind the screen. However, the player is able to retake agency through nontraditional means through game file manipulation.

Thus, Mechanics that disrupt the traditional boundaries of the game world create a dynamic where the player must confront their lack of control and reconsider their role within the narrative. This push and pull for agency between the player and the characters forces players to engage with the game on a meta-narrative level, questioning not just the rightful owner of agency in the game but also the broader implications of the power of agency in video games.

Points of Consideration

As a female player, there was only one part where I truly empathized with the story’s memo, which is when Monika gets deleted by the player after finally taking control of the system. To me, Monika having a voice of her own to express her raw emotions was incredibly important if she ended in “defeat”, and I felt that satisfaction when she uttered her disgust towards the protagonist for taking away her agency. Yet the ending I received was her “saving” the protagonist after Sayori gained awareness, with her final words including “I’ll always love you” and deleting the entire game. To me, this was confusing, unnecessary, and a sick twist that revoked her prior words and emotions. In the end, Monika was back where she started, trapped in a game and an overarching system fueled by her programmed love for him.

My final discussion question: who is truly the villain in this game? Is it the protagonist, the characters, or the system? What would defeating the “villain” look like as a happy ending for you?

Works cited:

Chess, Shira. Play Like a Feminist, MIT Press, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/stanford-ebooks/detail.action?docID=6270461.