I had never before thought of Stardew Valley as a game that invites this notion of “gaming like a feminist”. Originally, it was only another farming game with a reimagined and completely unique play style, vibe, and aesthetics that I always praised and looked for. I always spoke well about it for its originality but I also see now that the game is also just a lot more than that. The amount of freedom and choice the player has in the game allows the development to implement a myriad of different and complex feminist narratives and conflicts.

The chapter in Play Like a Feminist, Gaming Feminism, already highlights Stardew Valley as one great example of playing a game that focuses on implementing deep, multifaceted stories that players have the freedom to parse through. The freedom of these stories doesn’t just simply mean that the players have shallow, linear, choices in-game. Instead it is more defined as giving space to view each narrative or decision in the story through different perspectives that is not just the heterosexual masculine one, and is something completely up to the player. From the beginning of the game where you can choose the gender of your character changes dynamics and relationships with NPCs that don’t follow that perspective. In this way, Stardew Valley’s freedom and agency allows the player to play like a feminist. This is an excerpt, that sums this up perfectly (which I cannot make clearer):

“In [Stardew Valley], the structure denies the player any specific climaxes, existing in the never-ending narrative middle.Yet at the same time, the stories within Stardew force the player to think about difficult issues from relationships, to abuse, to mental illness, to environmentalism, to commercialization. The fame combines structure with themes in a way that allows a space for deeply feminist narratives.”

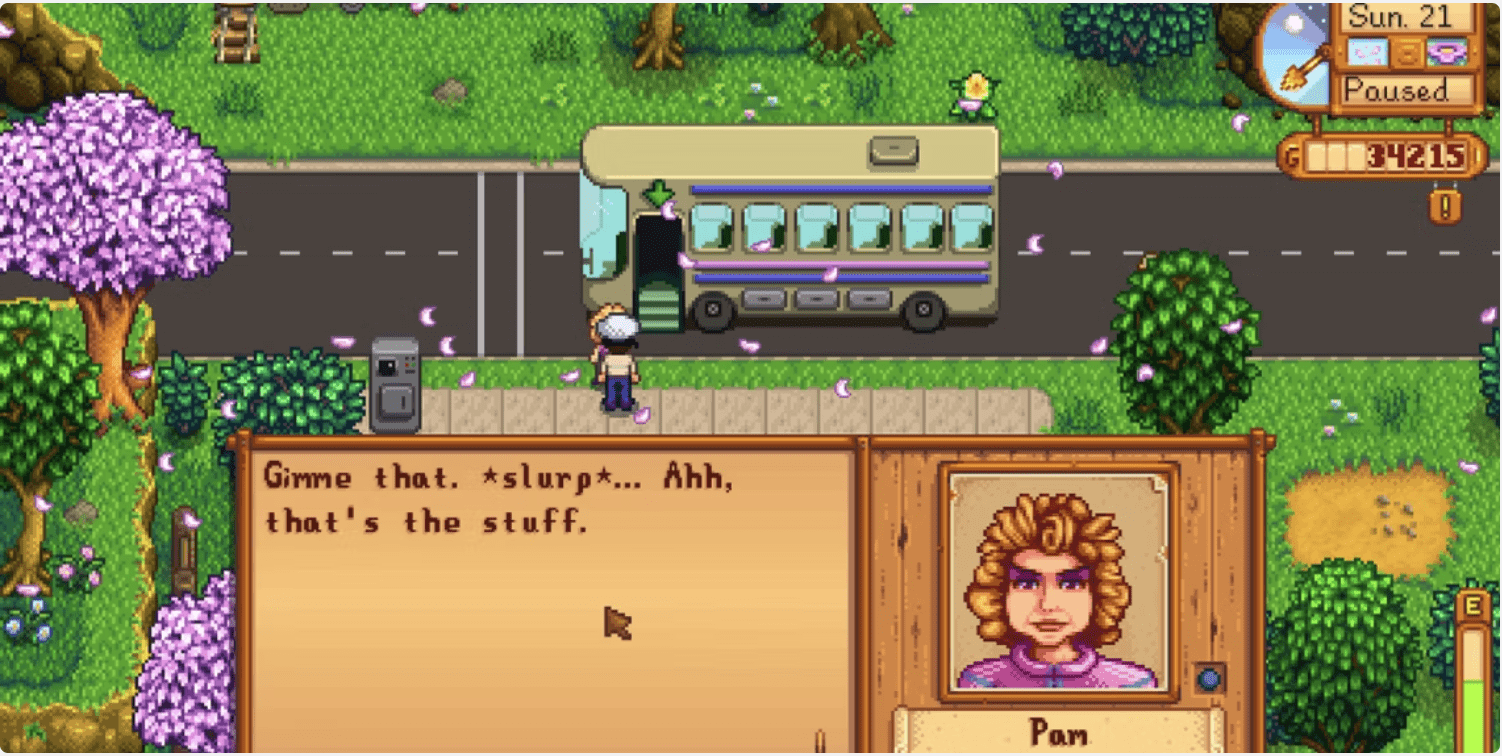

Stardew Valley is a game where you can play like a feminist because it respects and acknowledges the varying values of its many many players. It feels as though there is room for everyone to play with different motives. For example: just as in real-life where every one of your interpersonal relationships are different from another and you are allowed to not vibe with certain people, you can choose to do just that with the NPCs in the game. For example, the affair between Lewis and Marnie is a little suspicious so people might not like to get into that, while others drink that tea up. Linus’s way of life might deter certain players, while others love to interact with the guy. Sebastian is the most popular bachelor in the game, but others might say he’s too creepy. Yet all these decisions are not game-ending, and “life” moves on reacting to decisions you ultimately made based on your values.

This establishes a path for players to most likely insert themselves better into the game and follow the narrative as if they were personally affected by them. Because of this, Stardew Valley has a great and healthy fandom and fan interpretations, like head canons. In the book, Sarah Stang prompts these spaces to help define gaming feminism.