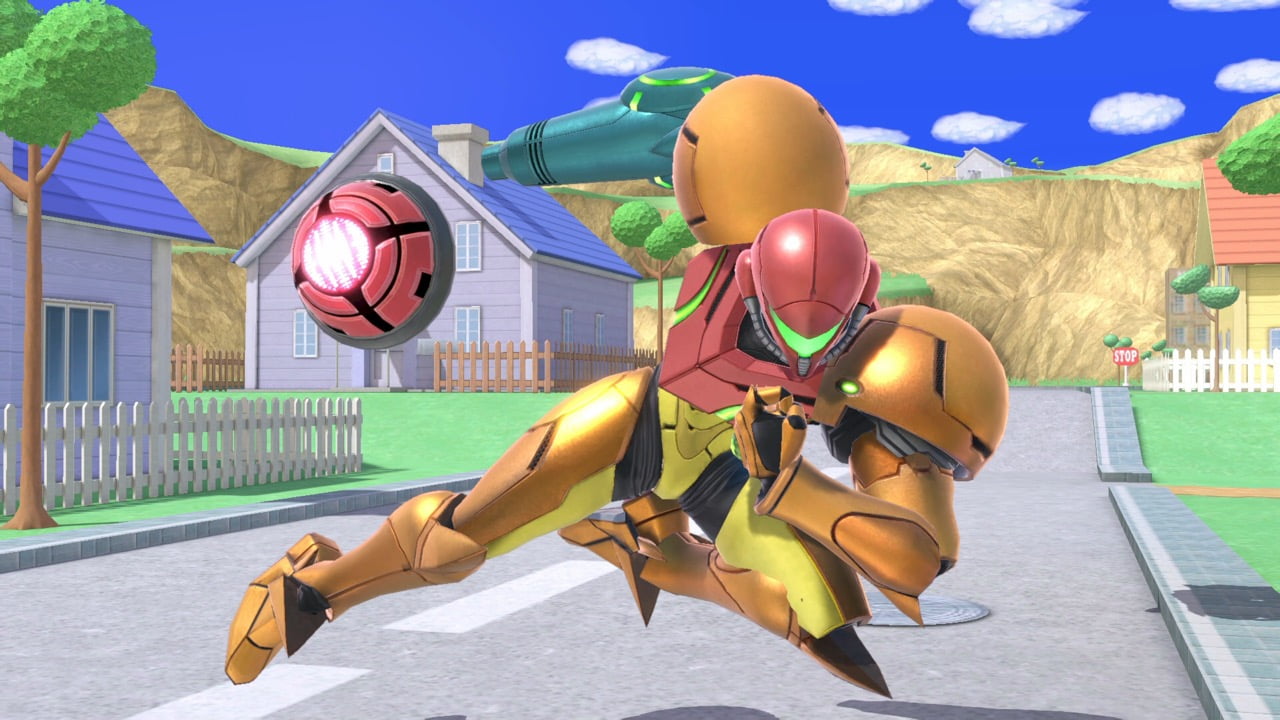

This critical play, I played a few rounds of Super Smash Bros. Ultimate for the Nintendo Switch. This game was both developed by Sona Ltd. and BANDAI NAMCO Studios and published by Nintendo and is suitable for all ages above a threshold that cartoon violence is tolerated (for me, this would be four or five). I love a good Samus round, and so I played her for the critical play, both Suit and Zero-Suit variants included. In my opinion, Super Smash Bros. occupies an interesting position from the perspective of a feminist. Although its very conception is seeped in games from the 1980s (Mario, Metroid, Legend of Zelda, etc.) when boyhood was the focus of the gaming market, I believe the game’s core values of diversity align well with feminist ideals. However, the cast of characters is indicative of the places where the gaming industry can be improved.

Samus was one of less than 20 explicitly female characters in the original Smash Ultimate roster. Of those, three of them are princes from the Mario series, three of them are versions of Samus, and Zelda and Sheik are the same princess as two different characters.

Here lies some strong issues from a feminist lens: a lack of women representation and a very specific kind of representation that’s there. Princess, in general, is a very stereotypical role to occupy. Samus is a bounty hunter, but her presentation is pretty ambiguous under her suit, which may be insufficient for diversity in the context of the other available woman-presenting characters.

Many of these issues are emblematic of gaming history and the industry itself, however. Smash is built off its readily identifiable characters, which will inevitably reflect the masculine-centered hegemony. This, I believe, is also what gives Smash incredible potential for the feminist. Any future characters added to the cast could truly be anyone. Smash—in recent years—has prided itself on many crazy picks for their roster: Joker from Persona 5, Banjo & Kazooie, Steve/Alex from Minecraft. This reduces the expectations people have for a Smash roster and has steered the game towards a broader celebration of the medium rather than on Nintendo’s specific cast of characters. Ultimately, feminism values diversity as a consequence of equality, which makes Smash’s structure particularly promising, but Nintendo would really have to provide an accommodating focus for future success.

Beyond the characters available in the game, the gameplay aligns with many of the points in Chess’s chapter on Gaming Feminism. Although Smash technically has a story, the bulk of players buy the game for its battle mode, which is what I played with my roommates (I’ve also never played the campaign). This provides a flavor of Chess’s focus on the narrative middle. Besides unlocking all of the characters, there isn’t much of a narrative climax in most people’s experience of the game. That being said, I’ll admit I did feel that climactic exhilaration when I eventually won a match (my roommates are very good), but this was far from the pinnacle of the game, as those feelings quickly faded as the next match began. At the very worst, its arcade-based structure diverges from narrative climax.

Agency is also a strong theme in this game. Players can select whoever they like, whoever interests them, unless you’re playing competitive, it usually doesn’t matter. Items are also available to balance the game for those who prefer to play (although my roommates and I didn’t play with items because we’re incredibly competitive). Many characters are also easier to play than others. Of course, it all depends on who’s playing and how much experience they have, but there are certain characters like Kirby which are more approachable for newer players compared to a fighter like Peach, who is far more complex (according to Reddit). I felt this as Samus, which is generally agreed to be an easier character. Many of her best plays come from just pressing the shoot button, a simple mechanic to perform but has plenty of room to master. While air dodging for my life, I kept in mind how important this sort of accessibility was. Picking a character isn’t a strong form of agency if the character’s capabilities are limited, either by ability or learnability, so including characters that require different skill thresholds is a healthy indicator of agency.

Smash certainly diverges in aspects from Chess’s vision of a better gaming industry, but playing it always reminds me of why I love games. The game encourages choosing who you like, and it centers goofy cartoon joy over everything else, which is an empowering emotion. The hope would be that Smash’s palette evolves as the gaming industry does, and maybe the edition fifteen years from now will boast a roster we can truly all be proud of as gamers.