For this week’s Critical Play, I explored the opening of Pokémon TCG card packs with some friends. Individual Pokémon cards have artwork designed by individual designers, and the concept of Pokémon cards was developed by designer Satoshi Tajiri. Although there is an option to open digital cards online, we opened physical card packs in person. In this Critical Play, I examine the specific addictive mechanics related to the opening of card packs—not the associated battle game that uses said cards.

Today, there are multiple target audiences for the opening of Pokémon TCG Card packs. One of these audiences is young kids who might be looking for a game to play with memorable characters where they can collect cards with their friends. Note that, generally, kids won’t be purchasing packs of Pokémon cards by themselves. In contrast, another audience (that I am primarily focusing on for this Critical Play) is young adults in their 20s who may have played Pokémon as a kid (and now find it nostalgic) and who have disposable income to spend on purchasing Pokémon card packs as a hobby or obsession. They may collect to complete collections and seek out specific cards (nostalgic ones or ones that are rarer and are likely worth more money). According to Bartle’s Taxonomy of players, generally, these cards appeal to Explorer-type players (they get to collect cards), Creator-type players (they get to assemble sets of cards), and Competition-type players (for people who want to get the best cards or “pulls” over others).

Through various mechanics related to probability, Pokémon TCG card packs put young adults at risk for addiction.

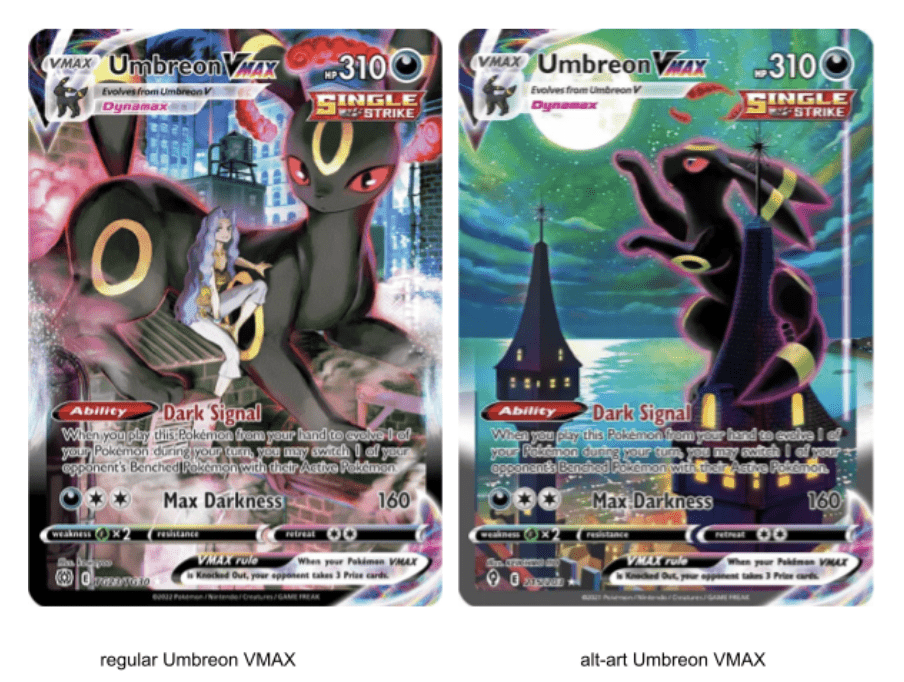

One probability-related mechanic is that of alternate-art (“alt-art”) cards. Certain cards have two versions: one with a standard artwork, and another, rarer one with an “alternate” artwork. Functionally, these two cards are identical: they are the same Pokémon with the same moves and same stats—the only difference is that one is rarer. Thus, when a person receives a less rare version of a card, they feel that they were “close” to getting the desirable alt-art version. An example of this is when my friend got an Umbreon VMAX card from a pack and they felt that they were “so close” to getting the best card in the entire set (the Umbreon VMAX alt-art) (see picture). This is a way of “recasting losses as potential wins” (reconfiguring loss as near misses) to “prompt further play.” This is very similar to how slots often make it look like you were close to winning (comparison). One method of “improvement” to make this even more addictive would be to add more, even rarer alt-alt-arts.

Regular Umbreon VMAX versus ultra-rare alt-art Umbreon VMAX. Images combined from TCG Player.

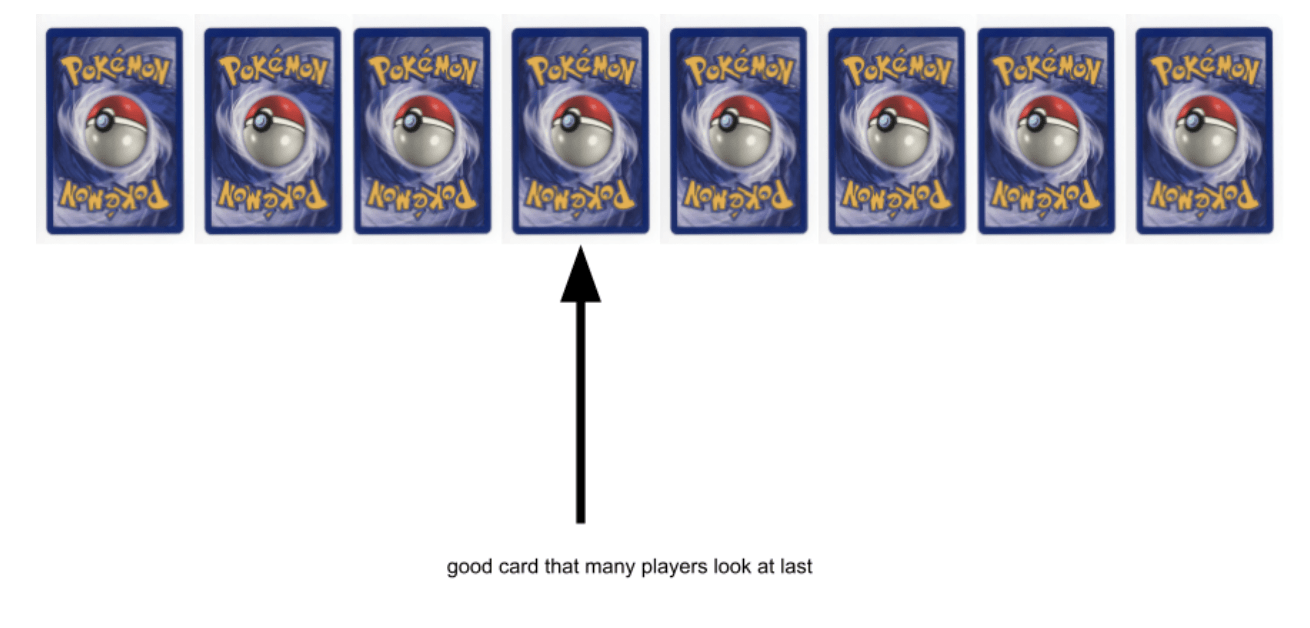

Another probability-related mechanic is that of guaranteed “pulls.” In general, every single Pokémon Card pack that one opens will have at least one good or holographic card of a certain rarity. This is somewhat similar to how Scratchers in California let you redeem a free game online after playing or how some prize wheels that you spin usually always give you something, even if it’s small—these are other forms of guaranteed “win” (comparison). Although in practice some of these cards are more desirable than others, it is guaranteed that a player will get at least something nice from each pack. In a set of cards in a pack, most packs of a specific type will place the guaranteed nice card in a specific spot (ex: the 4th spot) (see picture). Knowing this, two of my friends always chose to look at their good card last. Apparently, this is a very common practice, as they told me that I should do it as well and that my not doing it “physically pained” them. This practice of looking at the good card last results in an emotional build-up/arc leading up to a win, which feels good to the player. This also allows the player to “feel[..] that they control the outcome of the event” (feeling of control) even though the card is already fixed at the time the pack is sealed. This feeling of control and the emotional arc make players emotionally invested in the game. One method of “improvement” to make the game more addictive would be to have both a fixed spot for a good card (as there is currently) and at least one random one (to keep you on the edge of your seat, wondering when it will show up).

A third probability-related mechanic is that of different rarities. Within a specific pack, there is a certain set of cards that could be inside it. For example, maybe a specific pack is for a set of 100 cards. If there is one rare card that you truly want, it likely does not have a 1/100 chance of being pulled. This is because each card has its own individual rarity (similar to other card packs that also use probability—see Yu-Gi-Oh, Magic, and other games) (comparison). The picture below shows a very rare and expensive Charizard card whose odds of getting pulled are definitely worse than 1/102. This method of “lengthening the odds” is akin to “virtual reel mapping” of slots (another game that uses probability) (comparison) as it may psychologically lead a player to think that their odds of getting a card that they want is better than it actually is.

In summary, the opening of Pokémon TCG card packs is designed to be addictive. From alt-art cards that reconfigure loss as near-misses, to guaranteed pulls that lead to self-controlled emotional arcs, to different rarities of cards that lengthen odds, the game is rife with addictive mechanics.