For this next critical play, I played card games such as Poker and Blackjack. However, for the sake of the analysis, I’ll be focusing more on Blackjack. Although with debated origins, Blackjack’s inception is suspected to have occurred in French casinos in the 1700s. It’s a player versus dealer game, where multiple players can be playing at the same time. At its core, both the player and the dealer are dealt two cards. The player’s cards must either sum up to 21 or be higher than the dealer’s to win.

The game’s simplicity is ultimately what would put players at risk of addiction, especially in comparison to other casino games. Blackjack has an extremely low barrier to entry. Unlike Poker, the monolithic playstyle mechanic of player versus dealer means that there is less emphasis on the social aspect. With lesser distractions, the player can more easily follow the game. The straightforward arithmetic basis of winning also makes it easily accessible to most people This is opposed to other chance games like Poker where (depending on the version you play) you often have to memorize different combinations in order to fully understand the game.

Blackjack’s probability condition is hinged upon the standard 52-card deck. While trying to sum up to 21, each suite’s King, Queen, and Jack cards are all counted as ten. This means there are 20 / 52 “high” cards. This makes up the significant bulk of the cards at around 38%. In a normal playing round, players can choose to “hit”, where they draw another card to add to their pair, or “stay”. The ace card is also an extremely good card as it can count to be either 1 or 11, depending on what the player chooses. Once a player “stays”, it’s the dealer’s turn, where only 1 of their two cards are face up for the player to see. One would suspect that this gives the dealer an unfair advantage, however this is minimal, as the dealer’s goal is the same as the player’s. They have to beat the player’s sum, and ties often go in the way of the player. Rounds are started with bets and played until when players choose to “stay” or reach 21 (and win). Then the dealer goes and depending on the result, bets are divided accordingly.

For my playthrough, I played an offline version where we bet questions to ask one another, instead of any other resource. I played the role of the dealer (as my fellow players were new to the game). With its straightforwardness, new players learned quickly and did not flinch on the bets. (This could also be due to the fact that bets were made with questions and thus there was less overall risk).

Despite the higher probability of 10 count cards, during my playthrough, people often chose to “hit” while their sum was already high. Hovering around a 13 or 14 sum, players often pushed their luck and more frequently than not, drew a 10 count card and lost. The belief that a lower count card would arrive enticed players to keep on going. I also found the happy medium of “high enough” to beat the dealer to be around 18, as players often doubted their chances of drawing a 3, 2, or ace. This however didn’t mean they always won at this happy medium.

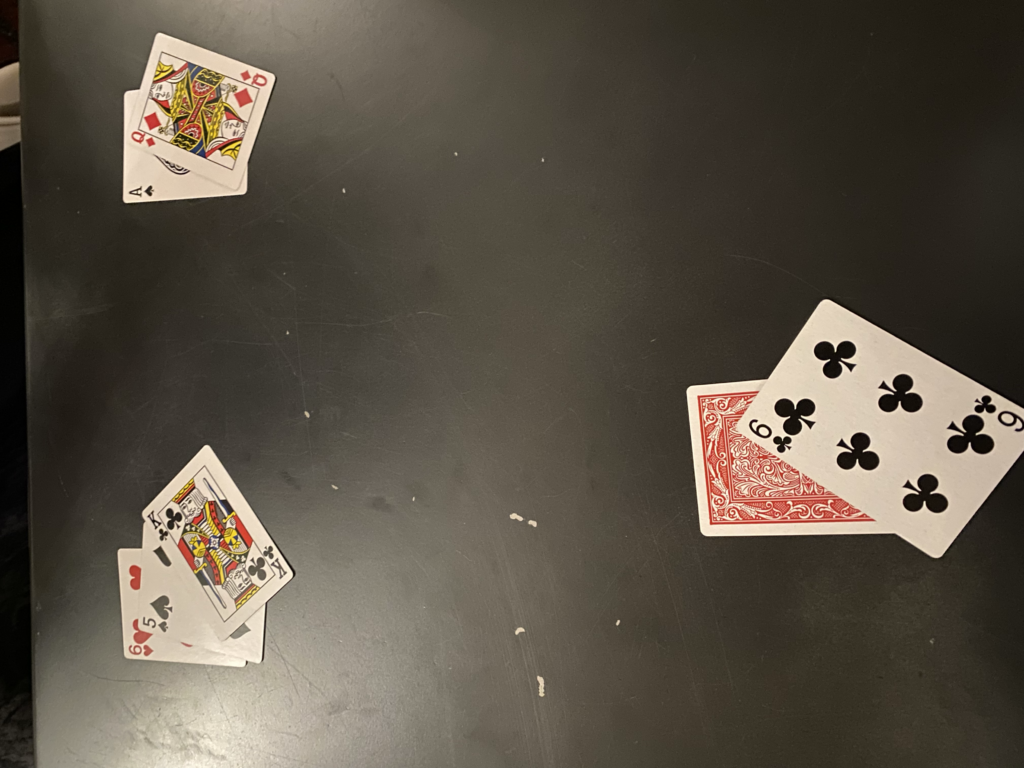

The most standout plays during my playthrough, are ones where a player split (divide their two starting cards into two different playing piles). During one of these splits, both of their suites reached 21, automatically defaulting me (the dealer) to lose.

[Blackjack 1]

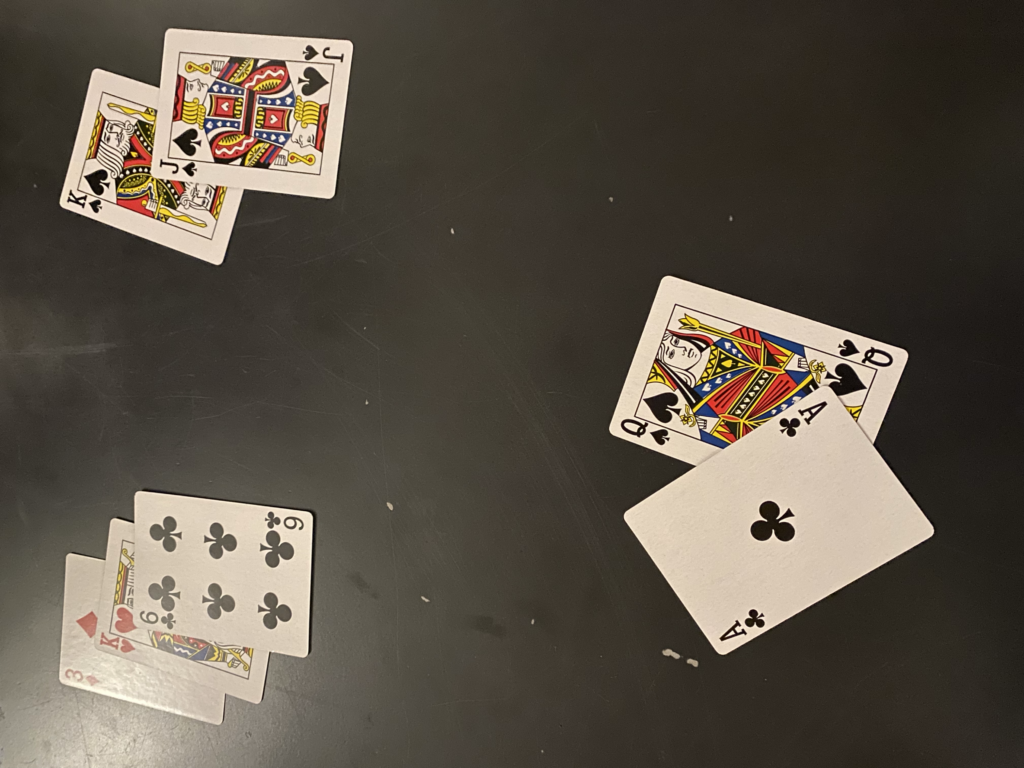

Another one of these plays from a split, the player reached 19 (3 + 6 + King) on one suite and 20 (King + Jack) on the other. However, upon reveal, I had 21 (Queen + Ace (11)).

[Blackjack 2]

These more standout plays tend to lower probability and impact a player’s willingness to play another round. On the one hand, the first example would encourage another round as players believe they’re currently on a streak of good luck. Conversely, when the dealer gets 21 off the bat, the players believed that I had used up my luck and was willing to play another round. Altogether it seems that the quick playability of Blackjack also feeds its addictiveness.