Few games are named after a mechanic, but Portal, created by Valve Corporation, is an exception. Portal, designed for puzzle game enthusiasts over 13, is available on multiple platforms, including PC, Xbox, and PlayStation. For this critical play, I used NVIDIA’s GeForce Now to play Portal through Steam. The central mechanic—using a gun to shoot white surfaces and create wormholes between two places—is so enticing, versatile, and pervasive that the game deserves to be named after it. In this critical play, I will argue that, by encouraging mind-bending “out of the box” thinking, the portaling mechanic perfectly enhances the narrative about defying an evil AI that seems to be in control.

The simplest use of a portal is for transporting yourself from one place to another. This can help you get across barriers, traverse distances, etc. This is the most obvious use and, for the game designers, the way to introduce you to the portals. The player doesn’t have any control over the very first portals through which they traverse. By gradually giving the user more control as the game progresses, the game designers achieve two goals simultaneously: they ease the player into the mechanics of the game and build a sense of empowerment. Initially, the portals are used in straightforward ways, such as moving from one platform to another or crossing gaps.

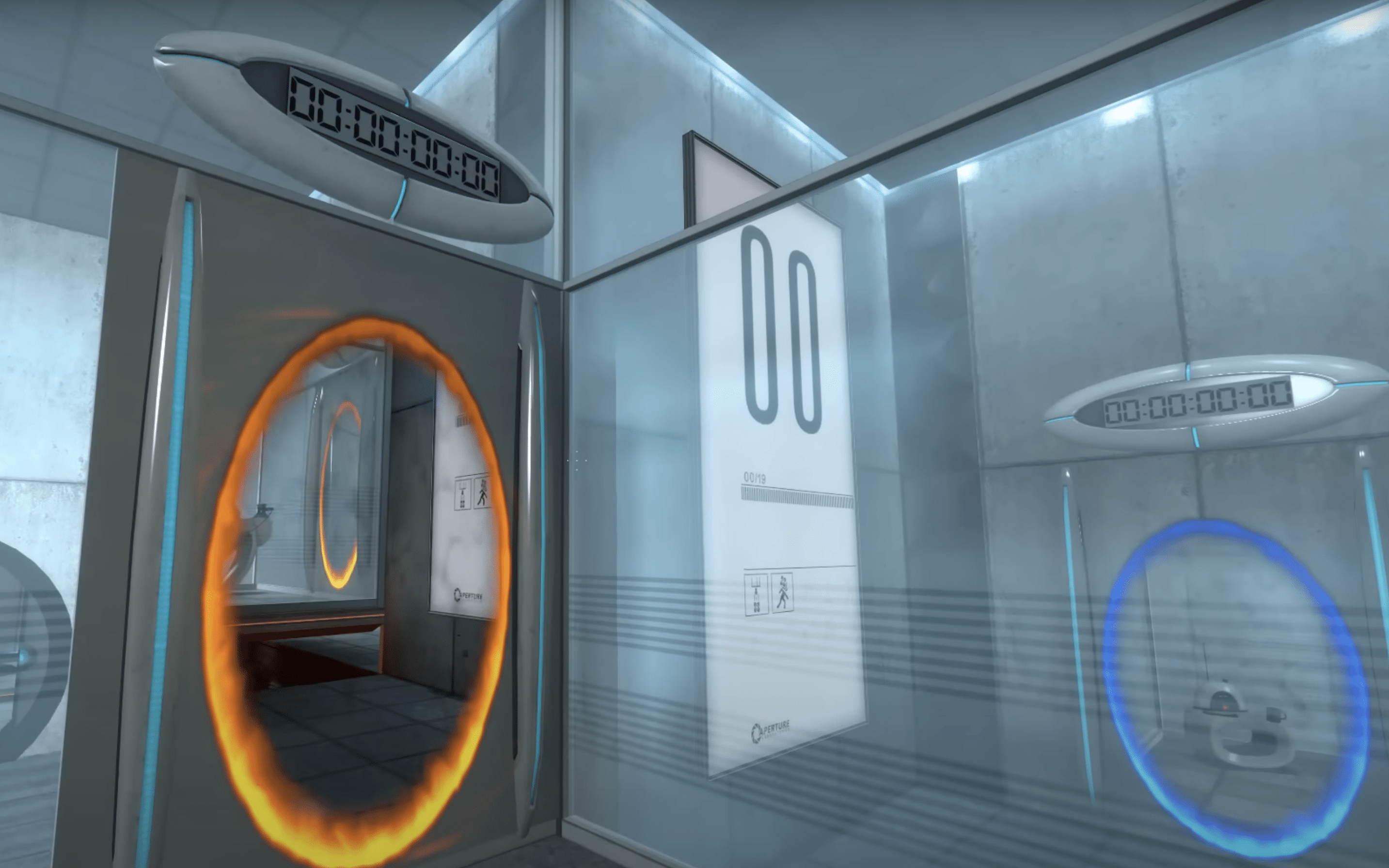

However, as the player gains control over both ends of the portals, the complexity of puzzles increases, requiring more creative and unconventional thinking. Below is an example of a puzzle where you have to jump off of a high place into a portal to gain enough velocity to shoot yourself across a larger gap. This dynamic, arising from the interplay of the mechanics of portals and gravity, involves more creative thinking and expands the type of thing you can do in the game.

While the player goes through the portals, they are accompanied by the disembodies voice of GLaDOS, the AI that is running the laboratory, testing your abilities (and allegedly the portal gun). In the early levels, the player has no choice but to do what she says. The only small act of defiance I was able to do was to shoot portals behind cameras so they would fall off. This tiny bit of rebellious was oddly exciting and I found myself itching for more. I found myself shooting off every camera I could. This ability is an early indication that portals can be used in ways that GLaDOS doesn’t intend, giving players a taste of rebellion, leaving them wanting more.

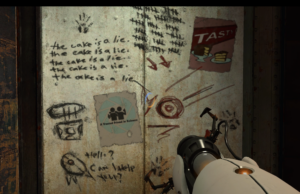

The game developers also utilize environmental storytelling to clue the player in on the fact that GLaDOS is evil. In order to reach some of these dens with graffiti, the player has to use the portal gun. This integration of mechanics with environmental storytelling further emphasizes the fact that the player may be able to defy GLaDOS while motivating them to do so.

In a later scene in the game, where GLaDOS attempts to leave no way out for the player, finally directly revealing her true colors, you can use a portal to escape certain death.

From here on out, instead of being clearly divided into different levels clearly set forth by GLaDOS, the puzzles are more seamlessly integrated into the environment of the industrial side of the Aperture facility, with fewer clear divisions between them.

Ultimately, the flexibility of how the portaling mechanic can be used grounds the player’s sense of control and defiance in a lab where they aren’t supposed to have any control. The fact that this mechanic can be utilized not just within the blatant exercises and puzzles but in ways that deviate from the path GLaDOS lays out amounts to a dynamic, exciting, rebellious gaming experience.