For this week’s Critical Play, I played Chess.com’s “Puzzle Rush” and “Puzzle Battle” minigames. The games were developed by the Chess.com team, which includes Erik Allebest, one of the site’s founders. Puzzle Rush and Puzzle Battle are accessible via the Chess.com app (for phones and tablets) and on the Chess.com website where I played it from my computer’s browser. They are designed for chess players looking to improve their speed and accuracy in identifying and solving chess tactics—the puzzles most often consist of scenarios that could happen in real games. Per Bartle’s Taxonomy of Players, Puzzle Rush and Puzzle Battle appeal most strongly to Achievers (you solve puzzles and get a score) and, in the case of Puzzle Battle, Killers (you compete directly with another player). The game consists of interaction loops for moves that make up each puzzle, tied together into an interaction arc of multiple puzzles until you finish the game.

Mechanics related to speed, problem-solving, and winning create a competitive training experience that translates well into speed (blitz/bullet) chess. Specifically, I argue that these mechanics make Puzzle Rush and Puzzle Battle useful tools for people looking to train for and improve at speed chess.

Broadly, Puzzle Rush and Puzzle Battle are races to solve as many chess puzzles as possible within a short timeframe (3 or 5 minutes). In Puzzle Rush, you try to set a personal high score (number of puzzles solved) which you can also compare with friends and other players. In Puzzle Battle, you solve identical puzzles at the same time as another player, and you see who can solve more of them.

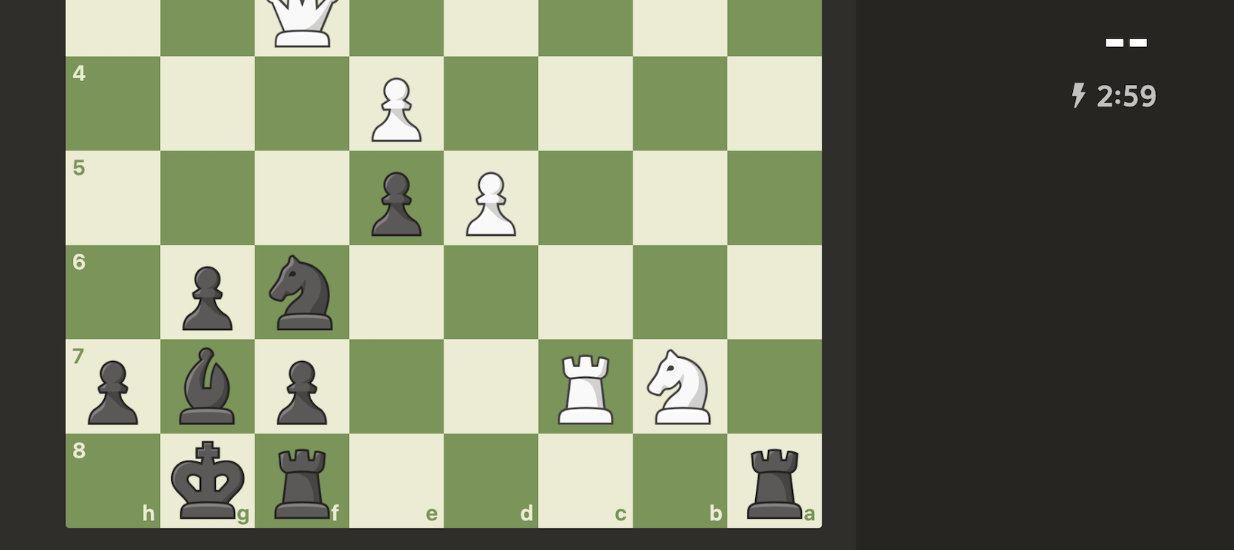

One of the mechanics of Puzzle Rush/Battle is the timer (the screenshot below shows how, other than the chessboard, it is the most important visual aspect of the game). Throughout a round of the game, you have a certain amount of time (3 or 5 minutes) to complete as many chess puzzles as you can. This leads to a dynamic of thinking quickly and moving quickly (each puzzle can consist of multiple moves) so that you can answer more puzzles (an aesthetic of challenge). This same dynamic/aesthetic is also present in normal speed chess (you lose if you run out of time and you have a similar amount of time to make a move), so this makes Puzzle Rush/Battle a good way to train for that. One area of room for improvement though would be providing more options for customization of the timer (ex: more overall time choices, time increments for each successful puzzle solved, etc). This would allow for Puzzle Rush/Battle to more precisely map to different time configurations of speed chess.

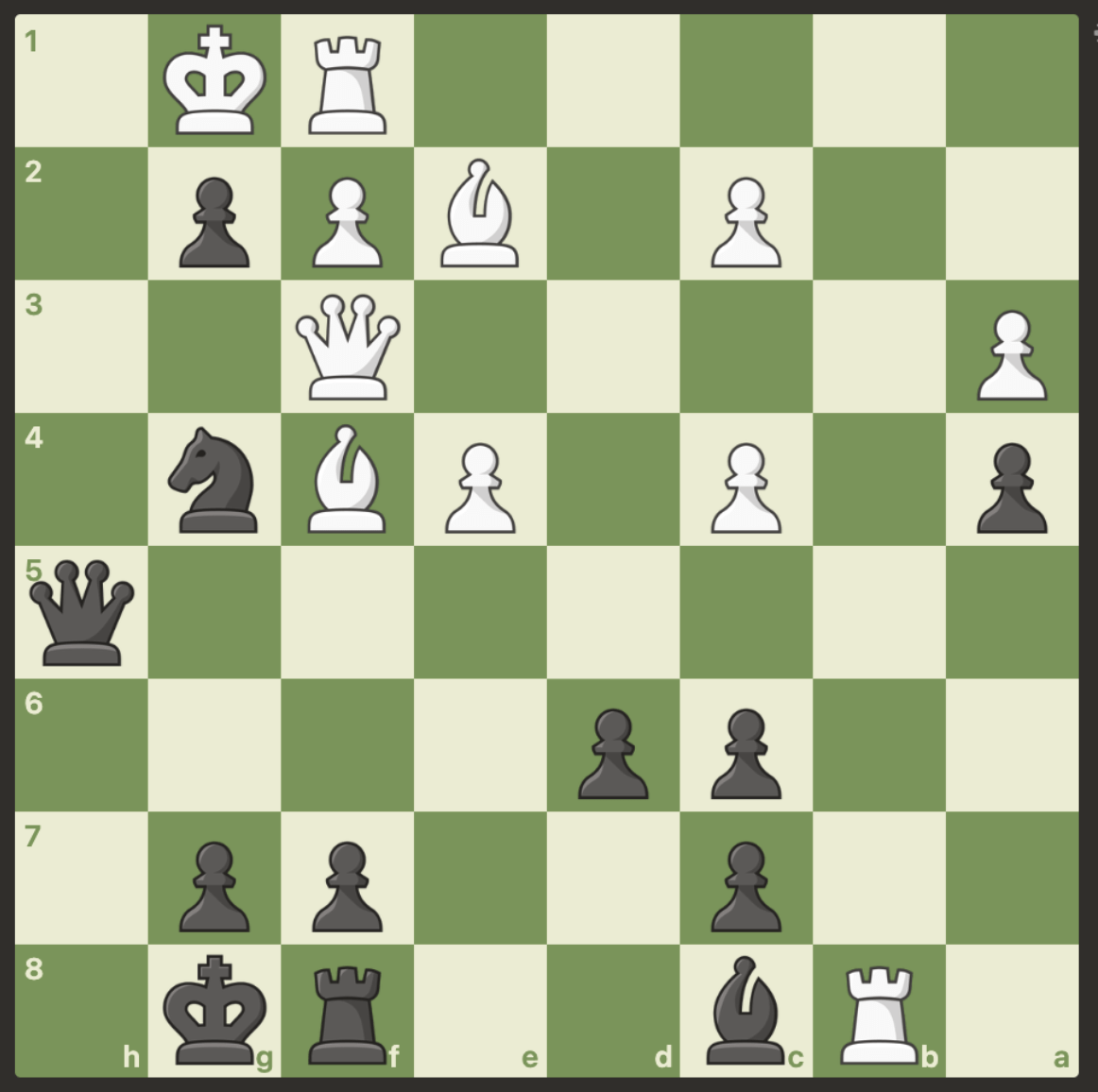

A second mechanic of the game is that puzzles consist of preset games or positions—they generally represent positions that could feasibly be reached through normal chess play (see screenshot below for an example of a preset puzzle position). There are many different types of positions/puzzles available: some basic ones include back-rank checkmates (a way to beat an opponent) and forks (a way to force capture of one of your opponent’s pieces). In practice, this means that players will try out many different types of puzzles or positions (dynamic). One way to improve this experience would be to allow players to customize the type of puzzles that they solve. For example, if I find a certain type of preset position/puzzle to be more challenging, it would be nice to have more puzzles related to that. This would translate well to real chess as it would allow me to spend my time training on puzzles that I am less confident in or quick at solving.

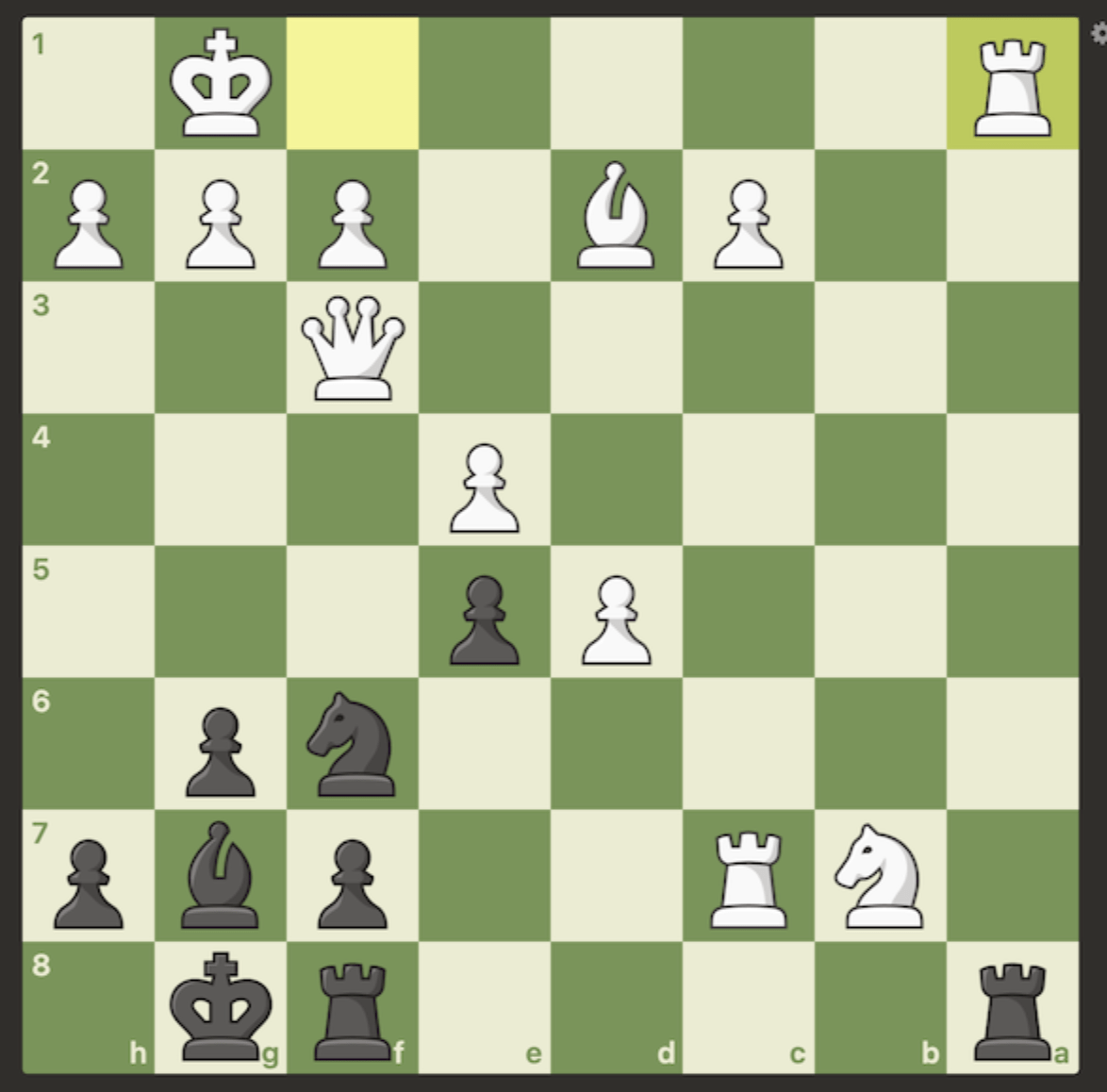

A third mechanic of the game is the increasing difficulty of the puzzles (the following screenshot shows an easy initial puzzle—a three-move checkmate). The game starts with easy puzzles (ex: one-move checkmates) and progresses toward harder ones (ex: multi-move sequences that win a small amount of material or prevent you from losing material). In practice, this allows players to warm up with simple tactics. It also means that, when comparing scores, you know that stronger players will be able to solve more puzzles overall. This all links with an aesthetic of challenge as the game continues progressing along a difficulty curve each time. One potential area of improvement would be allowing for players to configure their starting strength of puzzles. This would allow stronger players to skip some of the easier puzzles and move right to ones that are more suited to their level.

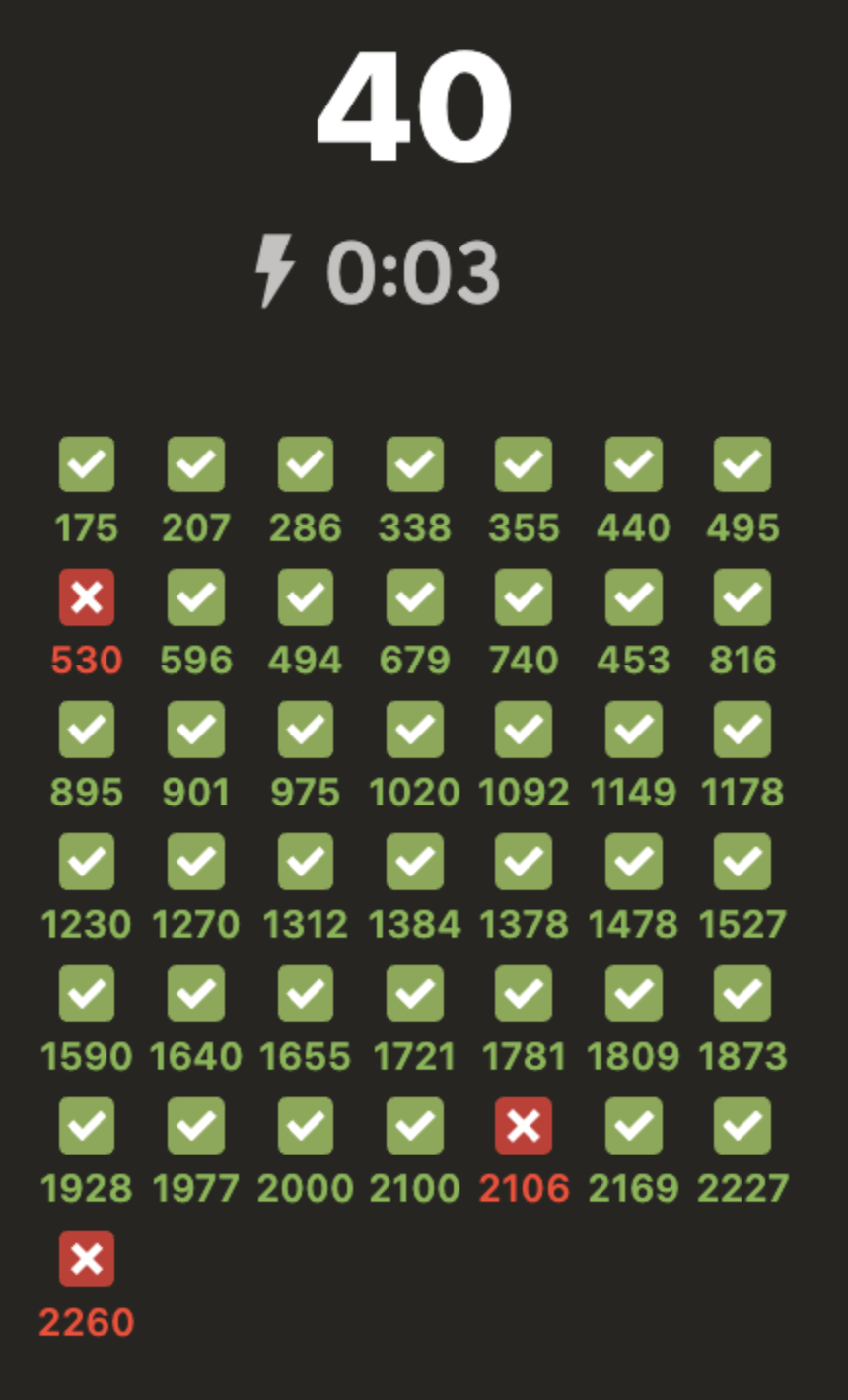

A fourth mechanic of the game is the three strikes and you’re out rule (the following screenshot shows me losing after three strikes). As previously mentioned, players have a certain amount of time to solve puzzles. However, if they make three mistakes, then they are also done. This mechanic prevents players from moving too fast and making too many unwarranted guesses (dynamic) in experience. This translates well to actual speed chess: if you make too many mistakes, you’ll likely end up losing the game, even if you make perfect moves otherwise. One area of potential improvement would be allowing for the configuration of this end condition (ex: two strikes, one strike, etc). This would allow for Puzzle Rush/Battle to be used by players of different strengths who might have differing levels of mistake tolerance.

In summary, Puzzle Rush/Battle is generally an excellent training game—many of its mechanics translate well to actual chess games. Most of the room for improvement lies around opportunities to allow for more user configuration of the experience.