During this critical play, I decided to play and highlight the game “Life Is Strange”. It was initially released in 2015 on console and PC, and is described as a Graphic Adventure Film. In this sense, it builds a mystery story, following an embedded narrative structure. Developed by Dontnod Entertainment and published by Square Enix, the game is composed of Episodes that essentially tell smaller stories, and summed altogether creates the narrative. Overall, Life Is Strange enacts many different mechanics to build narrative, however the main driving force is its time travel mechanic. The story is linear in its progression, however, by allowing players to turn back time, progression is able to be made in very clever ways.

To describe the effectiveness of this looping mechanic in the game, we first have to explain the nested pieces that allow for time travel to work so well. The game is set in a western high school setting, which is fairly familiar to me and much of the game’s target audience (adult and older players). In this sense, much of the clues of the mystery is hidden in the setting. Surprisingly, I was able to interact with most of the items, and characters in the game. Most if not all items offer a “look feature” wherein Max (the protagonist) narrates relevant information about. Her narration also serves as character building as the player begins to understand the world through her lens. Items range from books, posters on walls, camera equipment, to all sorts of materials. Essentially all the NPCs (non-playable characters) in the game are also interactable, with the more relevant ones having a speak feature. In this sense, the world is well fleshed out, and the narrative itself is told through the school setting, and school characters. Even with all these choices however, the game does have directional text that guides the player to the intended action in order to advance the story.

[Object Interactions and Action Guidance]

The main driving piece of narrative, however, is the narration of Max herself. Alluded to earlier, Max is the entry point into the story for the player. Being as how Max herself is new to the school, it makes the unraveling of the mystery sensible in relation to Max’s character. This within itself is a very clever way of telling a story, especially a mystery. Mysteries often hinge on characters to be compelling. Through the gameplay, the player is most intimate with Max as we hear her thoughts and feelings. It’s a great way of showing how Max herself evolves as a character over the course of the game.

[narration]

The last piece of this puzzle required for time loops to work is the core “choices” gameplay. When talking to different characters, Max often has at least two (and sometimes more) different choices in how she wants to answer. At its heart, this is how the game essentially progresses, in making the right choices.

[choices]

Some are much more consequential than others, and this is highlighted quite nicely through visual cues. When speaking with the principal after saving the girl in the bathroom from her death, the blaring redness on the screen and the close up to the principal’s face are nice indicators as such.

[harsher choices]

Now, with all these together, we’re able to see how the time travel mechanic fundamentally works and why it is so effective. With linear story progression, the game can often be paced like a book. However the biggest problem with books is, you can only move the story in one direction. After a character makes a choice, there is no ability to rewind and try a different path. Here, the artfulness of Life Is Strange as a game surfaces. It circumvents the difficulty of players making the wrong choices or not progressing properly in the game, by breaking the linearity of a typical story. Players can rewind and choose a different dialogue option to explore and glean more information from the game. Within this reason, I fully argue that Life Is Strange is able to maintain the merits of an episodic, more “standard” storytelling structure with its linearity, but also allowing gameplay through a “do-over”.

(I was busy having fun with the rewind to snap photos of it.)

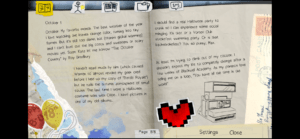

Other, smaller points that make this game stand out from its peers is its theming and immersion. From the beginning, players get the sense that Max is a little out of place, and doesn’t quite have a hold on her own identity at her new school yet. This goes hand-in-hand with the usual “collection of information” of sorts. In Life Is Strange, it’s Max’s diary. There, a record of all the characters and information learned is stored. It serves as a great reference point for players who drop the game and pick it up later, a great orienting tool. Thematically it serves well and the writing is very rich in Max’s voice.

[Max’s Diary]

Another point is during one of the game’s earliest sequences, Max walks from the classroom to the bathroom and puts in her earbuds. The music that Max is listening to is blasted for the listener. It doesn’t stop, until she reaches the bathroom and puts the earbuds away. This attention to detail is small, but deeply effective. It felt fully immersive by allowing the player to connect closer to Max, as it bends the auditory aspect of games to its fullest potential. While games are a very visual medium, the auditory components are utilized well in this genre of games (which I believe other games may fail to do so).