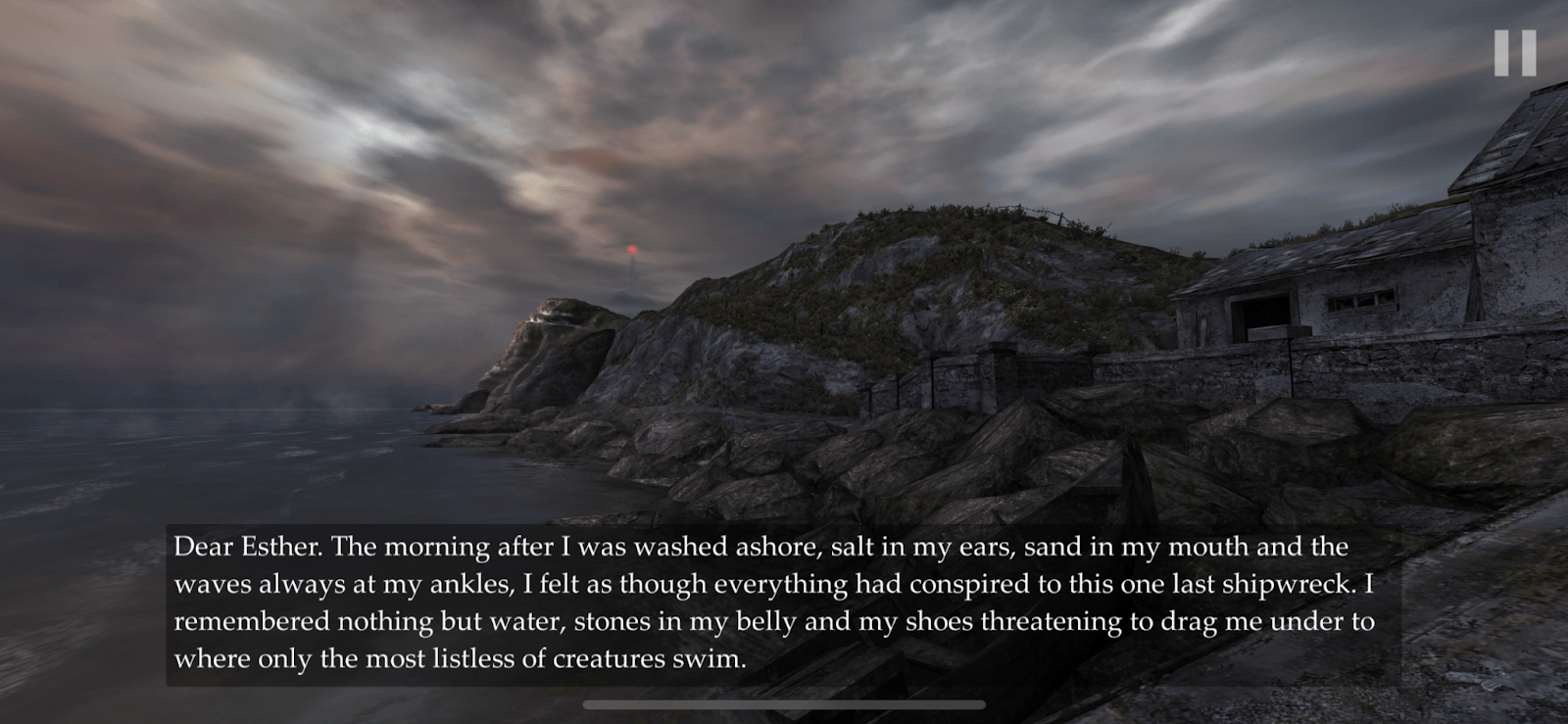

Dear Esther is a walking simulator developed by Robert Briscoe and The Chinese Room. It was released in 2012. The target audience is teens and adults and it is a single player game in which the player explores a remote island by walking, looking, and listening to narrated clues.

I argue that because Dear Esther is stripped of nearly all mechanics, the player is forced to focus on the story and attempt to understand the narrator, facilitating narrative and discovery as core aesthetics. However, the lack of mechanics leads to a dynamic in which the player spends most of the time contemplating the storyline, confused – and sometimes emotional, and therefore this game is for a very specific target audience. Moreover, Dear Esther illustrates that games can tell stories (if you believe that this is in fact a game – the App Store categorizes it as a story), but in entirely different ways than other media, and with extremely little interaction.

First, because walking and looking are the player’s only resources, they are forced to focus on the voice clues and therefore the narrative. In terms of the formal elements of the game, the objective is exploration and the only resources are the voiceover clues. The procedures are to walk and look and there are essentially no rules. The Magic Circle is confined to the game, aside from the fact that a player can bring in past experiences that affect their interpretation of the story and can leave with certain emotions. Given this set up, the player spends the entirety of the game holding down on their screen so that they can walk the island. With nothing else to focus on besides navigation, it is easy to get lost in thought about the many meanings each clue may have.

I argue that if more mechanics were added into the game, it would be at the cost of the narrative and emotional experience. For instance, even if a player was allowed to pick up objects, more mental energy and time would be spent looking for objects rather than focusing on the story. For example, at first I was looking through a room very thoroughly, thinking something might happen or that I would have to pick up/inspect something. However, after a few minutes I realized that I would hear the clues as I continued to explore, and reshifted my focus. Although this mechanic is extremely effective in channeling attention to the story, it made me feel passive and uninvolved in the outcome of the game.

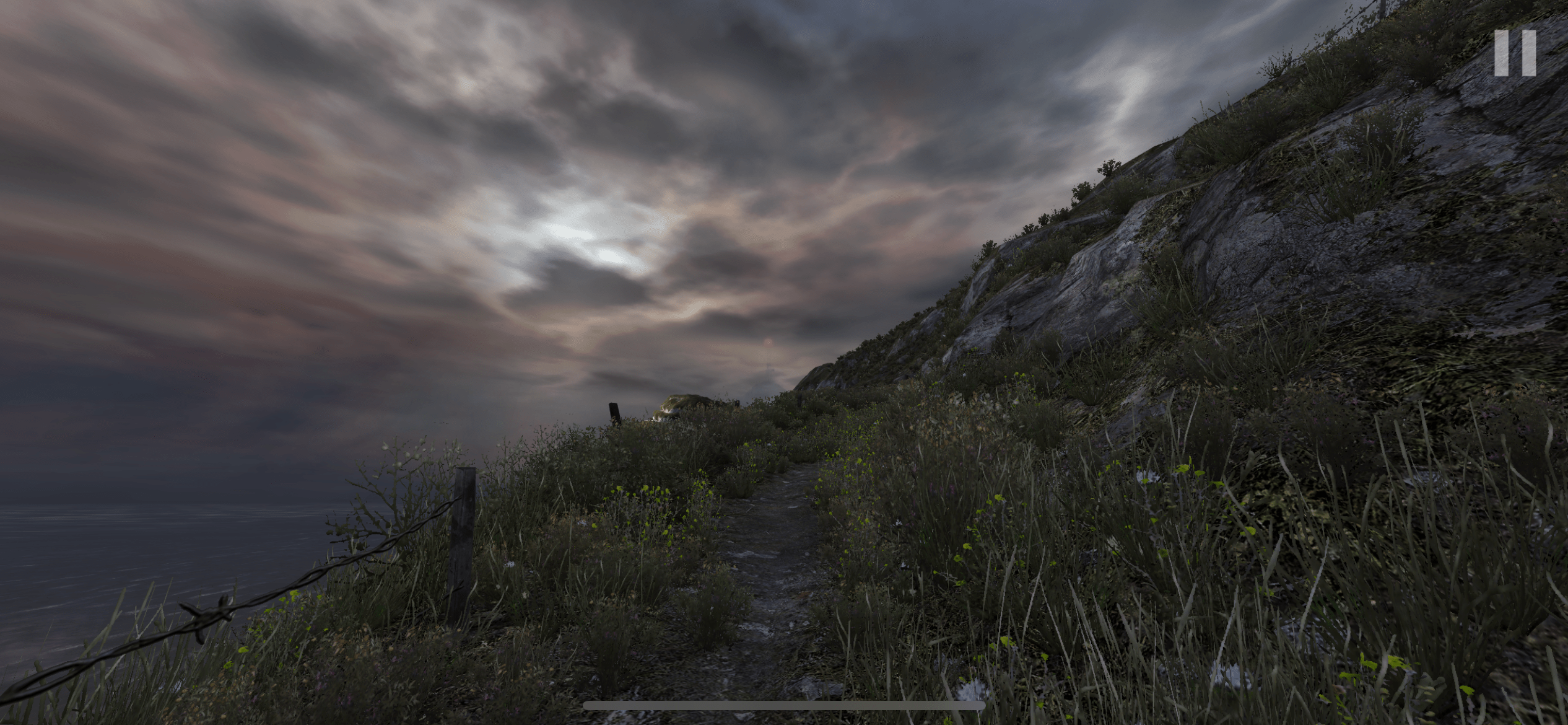

Additionally, the game pace is intentionally designed. The player moves relatively slowly, but this again leaves the reader more time to appreciate the story. However, the paths are not always labeled or marked, so at one point I was lost and felt frustrated trying to understand where I was supposed to go next. If I were updating this game, I would include more visual clues that the player is where they are supposed to be, as these would not sacrifice the player’s attention on the story.

Example of a visual clue that the player is in the right place. The fence on the side indicates that this path is part of the journey.

Second, the game heightens player emotion in an uncommon way and leaves room for interpretation, as the story is nonlinear and vague. The lack of directions and rules, the absence of other characters, and the creepy music and sounds lead to an unsettling and mysterious tone, creating an emotional experience. The story does not make a lot of sense, and I even started the game twice and noticed that different voice overs were played at the same place on the island, indicating that the story does not always unfold in the same order. This element of randomness gives each player a unique experience listening to the narrative, and is another way that Dear Esther diverges from a typical story.

Although it is accepted that games can tell stories, it is also known that games involve interaction. Dear Esther does utilize interaction, though it is so slight that I am not sure I would actually call it a game. This experience was not for me (I’m not a fan of creepy stories), but the game designers successfully used (lack of) mechanics, to create a dynamic in which players can use all their mental energy appreciating the island and the story, facilitating narrative and discovery as core aesthetics.