For this critical play, I chose BABBDI, released in 2022 and created by the Lemaitre Brothers (Sirius and Leonard Lemaitre). This digital game played through Steam feels intended for audiences 13 and older (the target audience is not explicitly specified).

In Babbdi, walking distinguishes itself as a meaningful way to interact with and learn about the game world, working hand in hand with the overall premise.

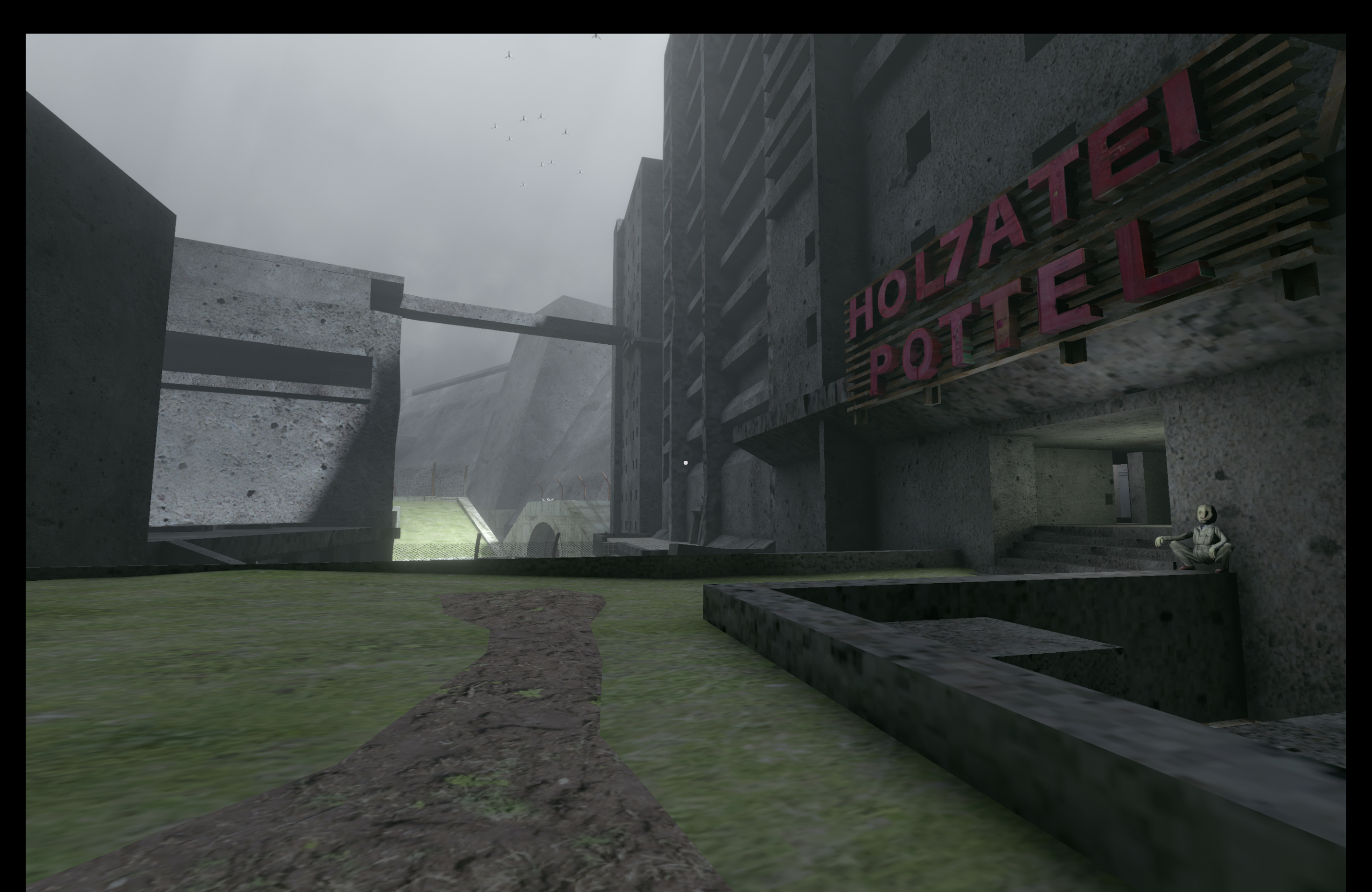

In Steam, the game’s premise is described as the following: “Find your way out of Babbdi. A short, first-person exploration experience.” The first-person and walking nature of the game creates a very isolating feeling. Even though you can interact with different people in Babbdi, these interactions are often limited to at most two sentences from the other person (in which you cannot talk to them, but they can talk to you – pictured below is one of the more memorable interactions).

The main form of interaction with the world of Babbdi is through moving around.

The game does provide other ways of moving in the game – a propeller, a motorcycle, a pickaxe – all of which are distinct from walking. However, either intentionally or not, these methods of moving are more clunky and difficult to operate. For example, the motorcycle traveled too fast and the pickaxe was only applicable when interested in scaling buildings (as seen below)

These modes, while providing a nuanced way to explore the world of Babbdi, ultimately do not offer any tangible ways for the user to progress toward the end goals. They are useful for a Birds Eye view, but much of the value in walking lies in the user’s ability to interact with people to collect information or to see and explore hidden nooks and crannies to gain secret items for the library. In order to accomplish any of the quests, the player needs to happen upon different people or objects, something that can most easily happen by the player walking around and exploring themselves.

The ability to walk and walk anywhere lends itself to creating a more free-form exploration, on top of an otherwise structured game.

As discussed in Lecture 4B, we know that levels can either be “linear” or “an open world guided by subtle design choices” (Alexander Brazie). Babbdi uses an interesting combination of these two concepts. While the player can seemingly complete any task at any point (breaking from the linear definition of levels and more so following the open world definition), there is an intended progression that they must follow (this ties into a critique that I provide later). These design choices and the nature of it being a walking simulator ultimately leads to the game being fit for more “achiever” and “explorer” archetypes under Bartle’s Taxonomy of Players.

When I played the game, I found that most of my time was spent endlessly wandering around, both to understand the landscape a bit better but also because I kept getting lost.

This brings me to my critique, which might be more unique due to my personal preferences and abilities as an overall player.

There were a few elements that I found confusing in the game. First, there was a distinct lack of tracking player progress, mainly in the quests and achievements. Throughout the game, I would see visual indications that I had completed a side goal or quest on the screen, but when I entered the library, everything except the current quest I was on (the very first one for all of my gameplay) was the same color. I am not sure if that was a choice to make the color choices more concise and intentional (solely highlighting the current question), but as a player, I was left wondering if that meant I would need to go back and re-complete these quests.

This next aspect may be more of a testament to my skill as a game player, but I found it quite difficult to navigate the overall world. There were a few times where I found myself stuck in the same location (or accidentally revisiting the same location I had already been to), and some locations that were very poorly lit, so I couldn’t tell if I was wandering down a dark tunnel (possible in the game) or if I was trying to pass through a wall. The navigation would perhaps be easier if there were some sort of map in the upper right corner, indicating where you were. If the game designers didn’t want to spoil the different locations players could unlock, a possible fix would be to gray out or silhouette those locations until the player “unlocked the location.” I think that the game design and overall look and feel were very cohesive and clear, but the game was hard to learn. Going into the game, I knew that I was trying to leave Babbdi, but was missing a few key actions that would have influenced my gameplay early on. This is mainly regarding the “Library”, which you are told at the very beginning that you can access by clicking the tab key. Again, a possible testament to my gameplay, but I did not click on the library due tothe assumption that a library, based on its name, would be a collection of items found along the way – rather than the desired quests that the player needed to complete.

To conclude, Babbdi, due to its nature of being a walking simulator, does provide an “illusion of choice” (as described by the Salon article). While players (like myself) can just aimlessly wander and walk through the city, by doing so, they are inherently choosing not to progress further in the game. The game design overall leans heavily into the liminal space concept, which does it make it unsettling but I would try it again just to master some more achievements.