Journey is a “walking simulator” developed by Thatgamecompany, available on Playstation, Windows, and iOS. Its target audience is (I believe) “non-gamers,” who are looking for a more theatrical and narrative experience than a classic game, although mostly everyone can play it, adults and children alike. I played the game on iOS on my giant iPad, and I really enjoyed how much I could really see the game on it. Apparently there is a multiplayer option, but I didn’t encounter anyone in my playthrough, probably because I’m playing on my iPad.

The central narrative of Journey is how a robed civilization causes environmental catastrophe through conquering and exploiting its natural resources, instead of listening to and “harnessing” it as it had done in the past. In its gameplay, Journey argues for the same thing. Typically, video games incentivize control, domination, competition. But Journey teaches us to read the “signs” that we see in the world around us with a gentle, kind eye. In other words, the largely unguided and gently nudge-y navigation (“walking”) through the world tells the story of a different kind of relationship with our environment: one that emphasizes careful observation, not dominance, and care, not competition.

In Journey, unlike many other sandbox puzzle-type games, there are no arrows, no extra-diegetic hints to where to go. You as the player must decide by reading the signs in the environment. Initially, you appear in the desert – the game then gives you a short demonstration of its very simple mechanics – and you must decide where to walk. I was a bit lost at first, just walking aimlessly. But then I saw a large mass in the distance – and I thought, well, I should probably go there. I had to sift through which signs were important. At first I thought it was important to find the little light bits that allow you to extend your scarf (and thus your duration of flight), and it took me a while to discover the mechanic of touching the little old, worn out banners to activate them (and allow them to do something). But the game led me to those old, worn out banners by putting them in the central location of the first “level,” in the center of the abandoned city – and once I had activated those old banners, by putting the statue that you had to go to exactly in front of you. At every point, beating the level was a matter of deciphering the clues that the environment gave you through sound cues and visual contrast. Because your “success” only relies on your attunement with the environment, the environment of the game became not something to fight or dominate, but something to work with, to tune into.

Walking also allows you to explore the sensorial pleasures of the game, teaching you to engage with your environment carefully. One of my favorite parts is when you “fly” with the other carpet creatures, skating through the city. It felt like a cut scene in a movie – I could wholly experience the feeling of skating through the sand, flying/floating with the other carpet creatures, and the music because there was really nothing to do. I didn’t have to focus on mechanics – whatever I did, I would end up where the game wanted to take me. Thus, instead, I focused on the beauty of the thing they had created. I watched the sun set in the horizon, the shhhhh sound of the sand (so satisfying!), and the other little cute carpet creatures flying. The environment, unlike many other video games, was not something created in order to tell the story. The environment is the story.

Overall, I loved playing Journey (although I am a bit upset that it didn’t save any of my progress – which means I must play it all over again in order to get to the final plot point that I haven’t finished!). I love the way that it teaches us to truly engage with the world – something that a lot of video games miss! The central “thing” of the game, the thing that it teaches, if games are really teachers, is the same thing that art or meditation teaches: the skill of careful observation.

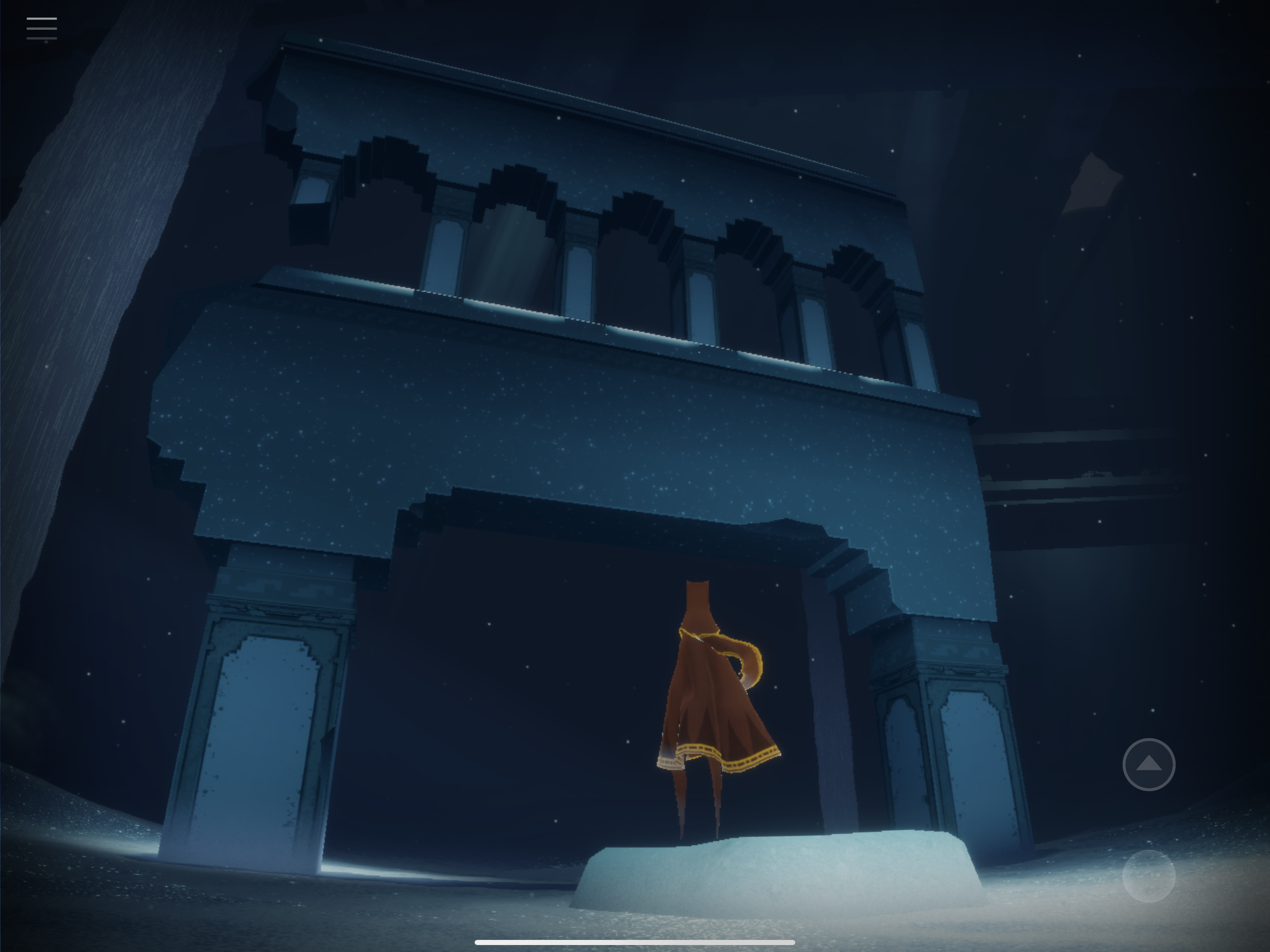

Me, taking the time to appreciate the beauty of the game. (Wow!)