Impromptu

created by Cyan DeVeaux, Khaled Messai, and Anna Gao in CS247G Spring 2024

Artist Statement

Impromptu!™ is an improv game centered around acting and roleplaying. Actors embrace a range of emotions, characters, or actions in front of an audience consisting of friends, family, or strangers!

The goal of the game is for actors to collaborate to put on a scene with given roles in a scenario and for the audience to decipher their roles. The joy of Impromptu! is performing the hand you’re dealt and navigating the hazards imposed on you and cooperating with your fellow actor.

When designing impromptu, we thought of the joys we had roleplaying and acting as people entirely different from ourselves. In Charades, audience members try to guess a word as the performer silently acts it out, but that’s a little bit lonely and quiet. We wanted people to collaborate to form a cohesive story given the hand they’re dealt and really embrace being a character rather than trying to convey a message as directly as possible.

Everyone has an image in their mind of maybe a Shady Merchant or a Jolly Farmer, it’s natural to think in archetypes, and we wanted to see how people brought their own mental archetypes to life with the additional challenge of weaving their storylines together, participating in a collaborative form of roleplay.

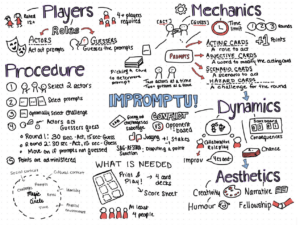

Concept Map (here for clearer image)

Initial Formal Elements and Values

Our team sat down and asked ourselves what we longed to see more of in social games. We loved roleplaying but thought many games didn’t properly emphasize actually interacting socially in your role’s context. We wanted a game where you could pretend to be a character who you aren’t, but rarely is that actual social dynamic of roleplaying emphasized in party games. It also felt like a lot of games were antagonistic! It is a lot of fun to compete with your friends, deceiving and tricking your way to victory, but lying to each other all the time is sort of tiring. We wanted our game to be a mostly collaborative environment.

Our development of Impromptu began with the idea of modifying the traditional game of charades into a richer, more interactive experience that centered around two players forming a scene collaboratively rather than just guessing the word. The core premise was to make it a pair performance with dialogue and interplay, presenting players with the challenge of cooperating with each other in order to create dynamic mini-stories in each scene. Some key innovations came with introducing the mechanics of scenarios and hazard cards to throw flavor into the scenes. Actors didn’t just have to perform, they had to navigate unexpected challenges and incorporate a strange setting as well.

We faced some critical design questions. How can we keep the audience as engaged as possible? It can’t center entirely around acting, they would have to participate somehow in the process. Initially, we thought that simply letting them guess the roles would be enough, but this evolved into hazards centering more on audience participation rather than just sheer restrictions.

.Overall, we wanted the game to be silly. It’s one thing to ask people to get up and put on a serious dramatic performance, it’s another thing to ask them to pretend to be a rich entrepreneur stuck with a farmer on a broken elevator. Our core values centered around creativity, inclusion, and highlighting social interaction between players in a way that incentivized them to interact with each other as much as possible. We wanted our game to be truly inclusive.

Testing Iteration and History

Through our playtests, we were able to adapt our game both in terms of the mechanics themselves and how we explained the mechanics.

Our First Playtest

In our very first playtest (in class), we had four players try out our game. The rules at this point were the following: Two players at a time would reveal the scenario but then act as the role cards for five minutes, in which the other two players could simultaneously guess the role cards.

We tested out this first way of playing, giving all players a chance to act, before collecting feedback. The players generally had fun acting out the scenario, but there were some issues stemming from the simultaneous guessing. Players felt that the guessing was distracting to their acting and that there was a bit of “stop and go” after each guess for the actors to determine if the guesses were close enough. With our initial set up of revealing the scenario and having players guess the roles, they felt that there was very little connection between the two and that players focused more on playing up the role itself, rather than interweaving the two.

During this first playtest, we had enough time to try out another play method, which was to reveal the roles but guess the scenario. We kept the initial guessing structure, in order to focus the feedback after on a different method of play. The players felt that this version was a lot more interesting, both from an acting and a guessing perspective. They enjoyed how vague the prompts were and suggested the potential for additional points to be incorporated – the top of the role card could include a vague prompt (i.e. “Frustrated driver) and the bottom of the role card could be a more specific prompt (i.e. “Frustrated driver who just missed their exit”). Players would gain more points if they guessed the bottom, more specific prompt.

Overall, players enjoyed the second gameplay experience more, but wanted more clarification on what they could and couldn’t say during their acting, as well as more streamlined guessing experience.

Our Second Playtest

During our second playtest, we had four players once again, with our main priority of testing out a new guessing procedure. This time, players would have two minutes to act, with others given one minute to guess after the two minutes were exhausted. If players are unable to guess within that first minute, actors then have the ability to try again for an extra two minutes, with the same minute after for guessing. We decided to test both play methods again (first one, revealing the scenario and guessing the role cards, and the second one, being vice versa), to see if the results from the first group carried over.

The players enjoyed the guessing structure, but only for the first round of guessing. They felt as if they had exhausted the acting afterwards, so the two minutes after felt far too long. Much like the first group, they enjoyed the second method (reveal the roles, guess the scenario) more. This playtest was especially interesting because the players suggested using simultaneous guessing rather than the structured guessing (due to the fact that they felt like feedback from the guessers would be helpful to structure their acting).

The players also introduced a novel piece of feedback regarding the confusion of team versus individual. The point system was individual but both the actors and the guessers ended up working together.

As an aside, this is the difficulty and the difference between our game and Charades – because Charades is strictly through motions and actions, the simultaneous guessing system works relatively well, because it doesn’t interrupt gameplay. However, because our game requires players to verbally embody their character, guessing during the acting versus guessing afterwards provided mixed reactions.

Our Third Playtest

During our third playtest, we wanted to see if a shorter period of time for our guessing would be enjoyable and if introducing teams would significantly change (either by improving or detriment) the game experience. Additionally, given feedback that our game felt quite similar to charades, we wanted to add in additional “challenges” to the cards – those being hazards and adjectives. We ended up having around 10 players total, with five on each team. At the beginning of each round, two players (one from each team) acted out a scene, with both roles and scenarios hidden. Each team could choose to add an adjective card to gain an additional point if guessed with the role. As rounds went on, we introduced sabotages/hazards that the teams could choose to play against the other. Additionally, we added a new feature for testing that involved a team losing points if the other team guessed their actor’s role. Through this playtest, we wanted to look heavily at the potential dynamic shifts with a team versus individual experience. Successes of the playtest resulted from introducing the sabotages/hazards – which the players found novel and fun (including “you can only sing” or “you can only say one word at a time”). Players offered that they wanted hazards that were a bit less difficult to accomplish. There were a couple of elements that we took away as improvement areas. First, the overall team dynamic resulted in a very separated method of play – the teams interacted during the acting portion but ended up splitting up to guess, which felt more disruptive than doing individual guesses. In this playtest, we confirmed a few assumptions: revealing the scenario and acting out the roles led to more fun and cohesion, the individual play feels more natural, and sabotages/challenges/hazards led the game a bit further away from feeling like Charades.

An important piece of feedback we received from this playtest was regarding end state. Players wanted a more clear cut way of determining when the whole game had ended – we had initially thought that with most card/social games, often these end states (or total number of rounds played to determine a winner) are not closely followed, which was why we did not provide a recommendation. However, players found it more confusing, which is how we realized that while most people don’t follow a recommended end state, it is still good to have especially when learning a new game.

We ultimately decided to remove the adjectives from the game altogether – given mixed feedback. Some players felt like they added a level of depth, while others disliked that they created a sense of “close-enough,” where instead of guessing the actual word, players were guessing synonyms and at some point, actors decided that the word was close enough.

Our Fourth Playtest

We had the opportunity to retest our game due to a surplus of players during the last in class playtest. The first playtest during class was the first time we had >4 players and it revealed some struggles the game experienced when expanded to a larger audience. Primarily, an unstructured guessing system wasn’t going to cut it for a larger crowd, the hazards were more a drag rather than a challenge, an ambiguous scenario drew attention away from the core mechanic, and there was rules ambiguity.

Consequently, we took the opportunity to quickly try out some solutions to the observed problems. We temporarily ditched the hazards until they could be reworked, returned to having the scenario be completely public, and guessing was changed to be a sequential affair during a structured period. It would proceed clockwise around the circle, starting on an arbitrary person, and the starter incrementing after every scene (the person who guessed first would then guess last next), like the small blind in poker.

Predictably, this favored the first people to guess, and it didn’t feel good when you “knew it” but were just at the back of the line. We considered that perhaps the informational advantage that favored later audience participants would balance out the disparity, but it proved insufficient. So guessing while the actors acted didn’t work, guessing at will during a guessing period didn’t work, and guessing in order didn’t work.

After this playtest we were left with some key problems. What incentive do actors have to act? How loose are actors allowed to be with granting points for words? And really, how are we supposed to make guessing equitable?

We settled on the following. Everyone has to carry a guess card (a piece of paper), and during the brief guess period, they write down their guesses and just get the one shot. Multiple audience members can now score points if they independently reach the same guess.

Actors also get points from being successfully guessed, as a heuristic for a successful performance. There was some concern about Goodhart’s law, namely that Actors would be incentivized not particularly to act, but to maximize their point gain. Another point scheme for actors was thus desired, and so we returned and expanded on the Awards system.

How could we improve Hazards? Rather than being simple restrictions on the actor’s expression, we thought that it may be better to incentivize both audience participation and acting mandates instead.

Our Fifth Playtest

So we ran one more playtest. It went really well! Guessing finally seemed like it connected and wasn’t a painfully laborious process. Keeping it timed, independent, and on paper removed the disappointment and chaos of everyone shouting all the time. Nobody ever really wanted to call for a sanction, which makes sense in a friendly game, and so there was discussion as to removing it entirely. It is probably a useful deterrent, because the alternative is no mechanisms to check abuses while also giving players agency to make judgment calls for themselves with point rewards.

Hazards also felt more fun! Changing them from “haha, now you can’t use words” to imposing mandates on actors to do things like monologue about their tragic past ended up pushing people to really get in character more. I hypothesize this is due to forcing them to form a coherent story in their mind of how they choose to portray their archetype.

The rule sheet underwent a rework as well. A denser rule sheet takes more time to read, but removes a lot of ambiguity about various situations. Offering a quick-start guide allowed us to get the best of both worlds, with the rules being reviewed as a refresher and answer-book rather than just reading it all in its entirety.

There were still some qualms about how some cards were very specific and some were very generic. Acting out “teacher” is significantly different from acting out “tech entrepreneur.” Getting the right mix of cards is something that would require quite some more time. By going super broad and generic, you lose out on a lot of the joy and specificity that some archetypes can bring. A teacher teaches, but tech entrepreneur can be some geek ranting about her new zero-knowledge trustless communication protocol, or some prick boasting about their Series A valuation. Teacher is significantly easier to guess, maybe less fun to act, but you’d probably feel a stronger sense of accomplishment for guessing tech entrepreneur. Either direction has its merits, but the primary issue is when they’re all in the same deck.

There are many possible solutions to this problem, ranging from dividing the deck into themes to publicizing the pool of available cards, but none that we settled on in the end. Future development would likely center around resolving this friction in the game.

Visual Evolution (clearer image here)

Our cards underwent quite a large design shift – our main focus with the prototypes used in the first + second playtest were to test out the prompts and the technical mechanics, but once we were more sure about certain elements (i.e. the role and scenario cards) then we decided to more fully develop the cards.

Final Prototype and Rules

After reviewing all the feedback from the playtests we conducted, here is the link to our final game, Impromptu: https://tinyurl.com/impromptucards

Impromptu is intended for 4+ players, the more players the more fun. The game usually has three rounds. The game is intended for groups of friends to play, or groups of strangers who are comfortable getting up and acting (especially being silly).

Materials include:

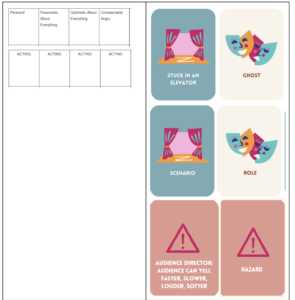

- Decks of:

- Role Cards

- Scenario Cards

- Hazard Cards (inspired by classic Improv games and challenges found here)

- Index cards to write guesses on

- Optional materials include a score sheet, and a stopwatch (on a phone) to keep track of time.

At the start of each round, two actors (randomly chosen, or volunteers) each draw a card from the Role Deck and only one card from the Scenario deck. The Scenario card (just one card per round) gets revealed to the guessers, but only the actors can see the role cards drawn for that round.

Both actors meet together to reveal their roles and briefly collaborate on how they will approach the scene for 10 seconds.

After this timeframe is over, actors call Scene! And begin acting out their roles for 30 seconds. Actors can and should talk, gesture, utilize props, and collaborate with each other to best represent their role.

After the minute, guessers will have 15 seconds to silently write their guess on their index cards and submit it to the actors. Actors read through all the guesses and distribute points to each audience member who successfully guesses the role – multiple audience members can score provided they guess correctly. Actors also score points if their role is guessed!

For this first cycle of guessing the point breakdown is as follows:

- A correct guess: 2 Points to the individual, 1 Point to the Actor

If at least one actor’s role remains unguessed, then the actors will have 30 more seconds to act again, followed by 15 seconds of the guessers writing their final guess. For this cycle of guessing, the individual and the actor each get one point for a correct guess.

A round concludes when each player has acted at least once in a scene. With an odd number of players, call for volunteers to act again! A volunteer will be awarded an extra point as part of their overtime compensation.

When the second round begins, the actors will flip over one hazard card, that they must both follow during their acting time. Point values and guessing structure remains the same.

During the last round, players unveil two hazards that must be followed when they act (two hazards will be unveiled for every pair of actors). If the two hazards conflict with each other (i.e. one says you can only sing, the other says you can’t talk), actors can opt to redraw one of the cards as needed.

Two Game Mechanisms for Our More Serious Improv-ers:

Optional Awards: The two players with the highest points will compete in a final scene to win “Best Actor/Actress.” No hazards will be used, but same structure of gameplay – two roles, one scenario. The person who wins that round will be awarded “Best Actor/Actress” (regardless of point value).

Optional Sanctions: Due to the nature of how the roles are worded, actors can offer leeway in awarding someone the point for guessing their role. For example, if the adjective was “nervous” but an audience member guesses “anxious,” an actor can choose to give them the point.

However, once the scene is concluded, the actors’ roles are revealed. If the audience feels that a point was awarded too generously, they can call for a SAG-AFTRA sanction and deduct one point from the actor and a half point from the guesser. This is a simple majority vote.

Directing Role:

For players who are less comfortable or otherwise hindered from the physical demands of acting, we still want you to be able to participate in our game! You can take on the role of director. Rather than players randomly drawing acting, scenario, and hazard cards, it’s all in your hands! It’s up to you to cook up entertaining combinations of potential roles in goofy scenarios.

To play the directing role, any time a player would randomly draw a card, peruse the deck, and choose the card you best see fit.

With multiple directors in play, directors can score as well! Directors alternate control over scenes and score following the points their actors achieve. Compete to be the next Spielberg, or mess with people like M. Night Shyamalan.

Video of Playtest

Video of Rules Instructions:

Packaging of Our Analog Game (clearer images here: https://tinyurl.com/impromptubox)