With 497GB of my hard drive free and a bit of time over the weekend to kill, I decided to give What Remains of Edith Finch by the developer Giant Sparrow a try. At a whopping $20 on the Steam store, I played the game from start to finish, averaging 2.5 hours. Although I played it on PC, the game is also available on multiple consoles and mobile! (Spoiler alert!)

Figure 1: A screenshot of me downloading “What Remains of Edith Finch” on Steam.

Figure 2: A screenshot of the end credits of “What Remains of Edith Finch.”

Although I was initially unsure what qualified as a “walking simulator,” playing through this game made it a lot more obvious. Instead of playing a game with special mechanics and win conditions, I was pulled into a rich narrative where I was experiencing the tragedies of the Fitch family myself. The walking quickly became the gameplay; I was progressing through the story and making physical progress through physical space. Because of this, What Remains of Edith Finch successfully immerses, intrigues, and allows investigation for its users through the simple mechanic of walking. Throughout this critical play analysis, I will speak on these topics.

To discuss the immersive aspect of the movement system, I’ll need to speak about the game’s mechanics and what aesthetics these mechanics invoke. Although the game was primarily centered around walking, there were many types of walking, and the movement systems still varied. Movement through moments of tenseness (such as walking down the basement stairs) was slower than movements of walking long distances (such as outside of the house). The simple movement was sometimes completely replaced with cutscenes of the protagonist crawling into a doggy door, climbing into a hatch, or hopping from branch to branch. Some forms of movement even transcended walking, including flying, swimming, and slithering.

Figures 3, 4: Screenshots of the “Molly Finch” scene, where the player swims as a shark and soars as an owl

This variety of movement is evenly dispersed throughout the story, making the game unpredictable, fresh, exploratory, and immersive. Although most areas were guided by the game through floating white dots, the placement of letters, and automatic camera movement, the affordances of certain objects like ladders and open hatches also drew the player closer to them. This (coupled with intentional lighting, which made it easier to progress) made me push up against certain objects, some of which weren’t interactable—like locked doors or closed chests. I felt like I was a part of the world, and that I could do anything. Although this wasn’t true, it kept me curious. Combined with the mysterious and question-raising nature of the Finch “curse,” I was completely engrossed in touching everything I could to figure out what would happen next.

Figure 5: Screenshot of the “white dot” indicator that revealed what was interactable

In terms of intrigue, I still find it fascinating that, although the game mostly consisted of me walking for two hours of gameplay, I never felt bored. I did experience a bit of confusion, but once I realized that a lot of the gameplay was linear, I became more trusting of the game’s guidance to get me to where I needed to go. (I initially thought there would be many branching paths since I unlocked an achievement at the beginning of the game for taking two separate roads to the Finch house.) Don’t get me wrong, though—contrary to what I stated in my main argument, this “walking” mechanic did not make this fun alone. However, as a person who is not a huge fan of “roaming” games (e.g., backtracking in metroidvanias), I was surprised that this gameplay format was still entertaining; I attribute most of this to how walking is combined with an interesting narrative and various “minigames” throughout the story. The game keeps its design choices very open-ended, such as the fates of every family member in the Finch family, which made me much more invested in figuring out more to potentially piece things together (spoiler: the game leaves off pretty open-ended as well, with no real reason to what the “curse” is). Each piece also then branches off into separate minigames, where the controls are simple (and accessible via mouse OR keyboard input) to continue to piece the story together.

Figure 6: Screenshot of a “swinging” minigame, where holding S would make you swing further back, and W for swinging further forward

The fun of investigation in What Remains of Edith Finch seems obvious now that I’ve talked about the mysterious narrative, which opens itself to player interpretation. (In fact, one of the game’s producers, Ian Dallas, claimed in an interview, “I expect that players will wrestle with their interpretations of these things. What we found is … another part of weird fiction is … your inability to ever really understand what is going.” — reported in VentureBeat (https://venturebeat.com/games/the-story-behind-the-haunting-what-remains-of-edith-finch). However, if we look at the game’s narrative and mechanics as separate sides of the same coin, the player’s sense of needing to investigate is also heavily facilitated by the game’s walking mechanic. The player is given a sense of agency and feels like they can control the story through walking: they get “aha!” moments from figuring out puzzles, go into secret crevices to find mini unlockable achievements, and can even walk backward the whole time if they’re feeling extra silly). Thus, the narrator creates an additive experience by adding lore and motivation behind the player’s actions.

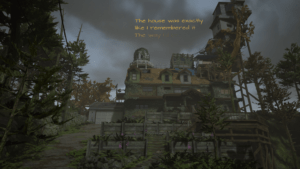

Figure 7: Screenshot of the Finch house at the beginning of the game, with narrative conveyed through overlayed dialogue

Before I end my analysis, I want to note that the game also had one major negative impact on me. The game did not start with a reticle (a little crosshair in the middle of the screen), so I quickly got motion-sick. It also forced my movement toward specific speech bubbles when I was not prepared to look in a particular direction (sometimes, it would make my character go in a total 180). Due to this, I had to take an extended break after the first hour of the game since the movements did not agree with me. I eventually searched for this issue and found that it was not uncommon; the developer responded to the public post, announcing that they had a setting to enable the reticle. Although I was not a fan of this opt-in reticle, it taught me a lot about how locomotion can be made better in games through smooth movement, a reticle (which, in my opinion, should be on by default), and non-forced gaze refocusing. If my P2 game requires some sort of similar movement mechanics, I will keep this in mind.