At CS 247G Game Night, my table group played Trumped up Cards (TuC), a judging game by Reid Hoffman. The game is only available as a physical game, to be played face-to-face by four to eight players (we had seven). Because the game attempts to satirically involve mature topics and to poke fun at Donald Trump, its target audience is liberal players (likely young adults or millennials). Although the game is listed as 13+, this age range no longer makes sense (13-year-olds were 6–10 when Trump was president—they may lack cultural knowledge).

Based on my group’s playthrough and analysis of the game, I argue that, for the current year, TuC is doomed to fail at being a fun and enjoyable game, given that its judging component hinges on outdated and awkward mechanics (judge selection, cards to be judged, special cards, and judge-overriding rules) and that satire ought to be timely and relevant. Despite this failure, if players navigate through an entire game, the game can still foster increased group connection due to a shared awkward experience (similar to hazing).

[Judging] Broadly, TuC is similar to other judging games like Cards Against Humanity. Players rotate through a judging role, selecting which card (from a pool of one card chosen per other player) best fits a known prompt. The ownership of each card in the pool is not known to the group—only the winning card per round’s owner is revealed (critique: making all players’ cards public would foster more group discussion and bonding).

[Judge selection] After reading the rules and dealing cards, our playthrough began with the selection of the initial judge. The game indicated that we should select the richest player. There was some tension here which was resolved when players selected the player who had the most resources in a previous game (“he had the most money last game, he should start”). I found this mechanic to be a great introduction to the awkwardness of the game. Forced reflection on personal wealth and capitalism may be important for affluent players and is one of the game’s few timeless portions.

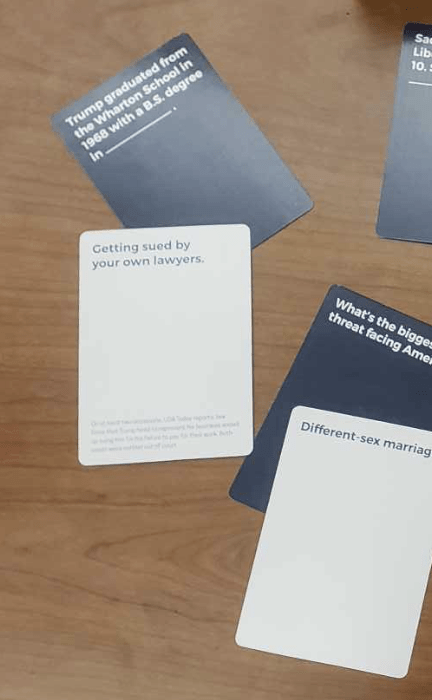

[Cards to be judged] Onto the answer cards, many referenced specific Trump moments, such as taking digs at certain groups of people based on protected class. However, these cards landed flat in the satirical sense, given the most publicly covered Trump comments were years ago. Criticism and satire should be timely, otherwise, they seem awkward and out-of-touch/place. I won some rounds by playing a liberal spin on them, which seemed to be appreciated by judges and other players looking for a break from the outdated satire. For example, I played that “different-sex marriage” was the “greatest threat to America” (see photo). Once players realized the card referred to heterosexual relationships, it was immediately chosen. Some cards also included small text at the bottom explaining their context (see photo). Squinting to read this out loud disrupted the game’s flow (increasing awkwardness) but was nice for players who might not have known what the cards represented. Critique: the size should have been increased to be readable, and the game should have asked for them to be read during judge evaluation.

[Special cards to change the judging process] Special cards (a new resource/formal element) included one (which I did not play) to silence another player (prevent her from winning) for being a woman. The card also notes that, in the name of equality, I can also silence a feminist man (shoutout to my nonbinary tablemate who appeared immune to this card!). Critique: say “a woman or a feminist of any gender” so that it can make its intended comment while still being playable against anyone. The dynamic of not playing these targeted special cards was shared, as discovered in our table’s debrief. Ultimately, it led to our group bonding after the game over this awkwardness.

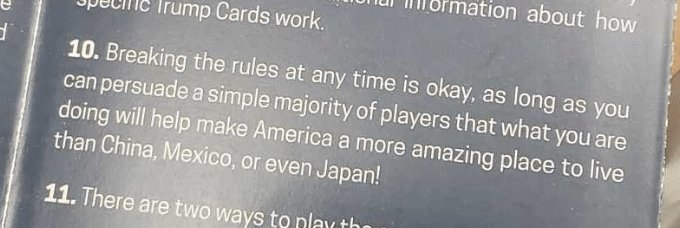

[Rules to override the judge] One rule in the rulebook (see image) lets players make up their own rules/actions by majority vote. To try this out, we initially tried giving all players (except one—the judge) free answer cards (points). This passed 6–1 but felt gimmicky. Ultimately, it seems the point of this game is not really to win it by any means. After a few rounds, one player used this rule to end the game. We unanimously agreed to be free of it. Critique: we could do without this rule, it’s overly gimmicky and doesn’t contribute to the game.

“Who’s going to write a good critical play about this game?” Silence. “Not me,” responded two people. We laughed. At least we bonded about the awkward/unpleasant experience of playing TuC in 2024. In that sense, all of the awkward mechanics and rules around judging actually brought us together after we exited the game’s magic circle.