Cards Against Humanity is a teen/adult get to know you game that’s played with a physical deck and revolves around players responding humorously to prompts, judged anonymously by a “Card Czar.” Players win rounds by playing the funniest or most appealing card, which would then be chosen by the Czar as the best answer that turn. Because of this, naturally the Card Czar’s plays a huge role in shaping how players interact with each other and enjoy the game. For one, the Czar player has the power each round to pick the funniest response, which implicitly forces players to think carefully about how they can choose the best card to appeal to that Czar’s sense of humor. Unlike “Apples to Apples,” where the responses are pretty safe, CAH pushes boundaries with darker and more controversial content. This setup not only changes how players strategize but also puts the group’s dynamics on display. In fact, my best gameplay experiences came from playing with groups of close friends or those I already knew very well.

Going off of this, it’s very important to understand the other players’ comfort and tolerance when it comes to edgier humor. Because the cards in the draw pile are often very provocative or explicit, the game often naturally calls for very edgy, dark humor. However, each round the Czar changes, which shifts the game’s power dynamics every turn. Because of this, players must adapt their responses based on their understanding of the new Czar’s humor, and navigate carefully, balancing between shared laughs and potential discomfort. This dynamic perfectly illustrates the MDA framework, since here the basic rules of CAH shape the group’s interactions and the overall vibe.

For instance, I played Cards Against Humanity twice this weekend. The first time was with my roommates and a few other very close friends, and the second was with a group chat of 247G classmates. Because of how the game is structured, naturally the first gameplay with my close friends was much more interactive and fun compared to the second time. This is not to say that the second time with classmates wasn’t fun, but the realization I had was that several times I was experiencing a feeling of nervousness or awkwardness before playing a card. I was constantly questioning whether the humor was appropriate for the group, and whether the rest of the players would even get the joke I was making. From this experience, I realized that in these kinds of settings, the focus shifts away from trying to make the Czar laugh (which is the true goal of the game) and instead becomes a game of trying to figure out what’s okay and not okay with the entire group. This definitely has some novelty and fun in and of itself, but after playing that round, we all agreed that the shared feeling of nervousness and apprehension definitely negatively affected our gameplay to some degree (at least in the early rounds). It also inhibited us from playing the card we wanted to play, since even though we thought it was the funniest to us, we weren’t sure if the Czar would like it, which naturally lowers creativity and expression.

Technically, this is only an issue if a player wins a round, since the Czar then asks who played the winning card. Otherwise, the game requires anonymity in how responses are submitted, since the Czar’s judging should be objective. In theory, this feature encourages bolder humor by providing a safety net, and lets players push comedic boundaries without direct personal accountability. However, during our playing, it was extremely common for after the round to ask each other “oh my god who played that card” or “that’s crazy, who played that one” and other similar comments. Because of this, no matter what your card was almost always revealed at the end of every round, which occasionally was awkward upon reveal (especially if you didn’t win that round and the joke didn’t land with others). Of course, this awkwardness is also part of the charm and aesthetic of the game, but it only really feels welcoming with a close group of friends. However, once everyone begins discussing their card after judging, it invites a range of reactions from the group, which ultimately reveals individual and collective thresholds for humor/group dynamics (which I found to be a huge help when playing with those I didn’t know that well).

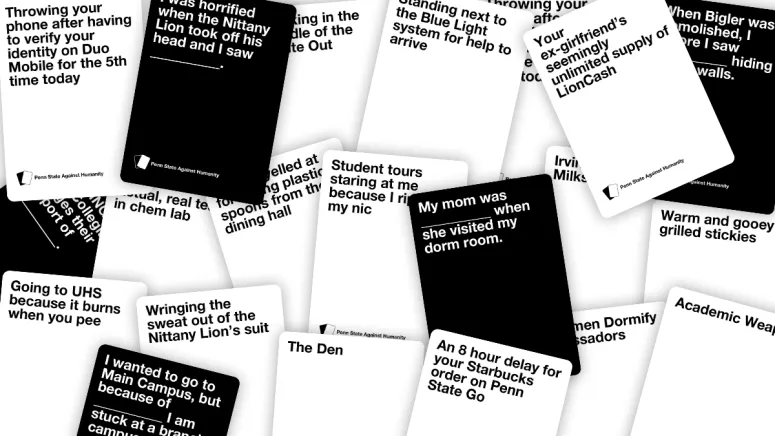

When comparing Cards Against Humanity to its sister game Apples to Apples, both games involve matching cards to a prompt with a rotating judge. However, CAH’s choice to incorporate shocking and potentially offensive material sets it apart, raising the stakes and deepening the impact on social interactions, which is a mechanic that I think helps foster connections or reveal rifts within groups. From a learning perspective, Cards Against Humanity’s reliance on shock value and the potential to offend can be seen as a flaw. A possible improvement might be offering customizable content packs that let players adjust the game’s themes to better fit their group’s comfort level, thus making the game more inclusive while keeping its core appeal.

So while the game excels at exploring humor, boundaries, and relationships, CAH also faces challenges in balancing inclusivity with its edgier content. For me, if there’s a way to ensure that players can play the cards they want to play, without having to worry about perfectly tailoring their answer to what the Czar wants, then the game would be perfect!