The Million Dollar Doodle (MDD) is a game by Flying Leap Games in which players create and pitch ridiculous business ideas to hilarious effect. The game is intended for ages 14+, as younger players may struggle with some of the key tasks the game requires (e.g. writing a review of other players’ companies or giving a product pitch). While playing MDD, I sought to understand how the game handled pitching and voting mechanics, as these are elements I hope to integrate into my group’s social mediation game. Below, I compare MDD and my group’s game (Posh Pooch) to understand how the games approach social dynamics.

Objectives

MDD and Posh Pooch have similar objectives and therefore experience similar problems. Both are judging games that require players to give a pitch, and in both the pitch that receives the most votes wins. Because these are both party games, players have an unstated goal of making their friends laugh, as socialization is a main draw of the genre. For the most part, both objectives align, as players are most likely to vote for the pitches they find the funniest.

However, a hyper-competitive player may shirk the goal of socialization in pursuit of being “the winner”. This kind of player, who seeks fun by dominating the competition, can ruin other players’ fun. In MDD, pitches are based on a company logo, a slogan, and a customer review all written by other players. One of the players at my table said, “If all I cared about was winning, I would just intentionally ruin other people’s pitches. Making good drawings doesn’t help you win”. Because players contribute to each others’ pitches, having fun requires all players to contribute to each company concept in earnest.

Posh Pooch, rather than hoping there are no problem players at the table, tries to channel the competitive energy mechanically. In Posh Pooch, pitches are based on a set of accessories the player uses to dress up their “posh pooch”, acquired by drawing randomly from a central deck or by trading with other players. However, players are allowed to lie when they trade, promising one accessory but secretly handing over another. Additionally, we are experimenting with allowing players to play accessories on others’ dogs right before the pitch stage. By implementing these mechanics, we’re hoping to allow for both competitive fun and socialization.

Physical Components

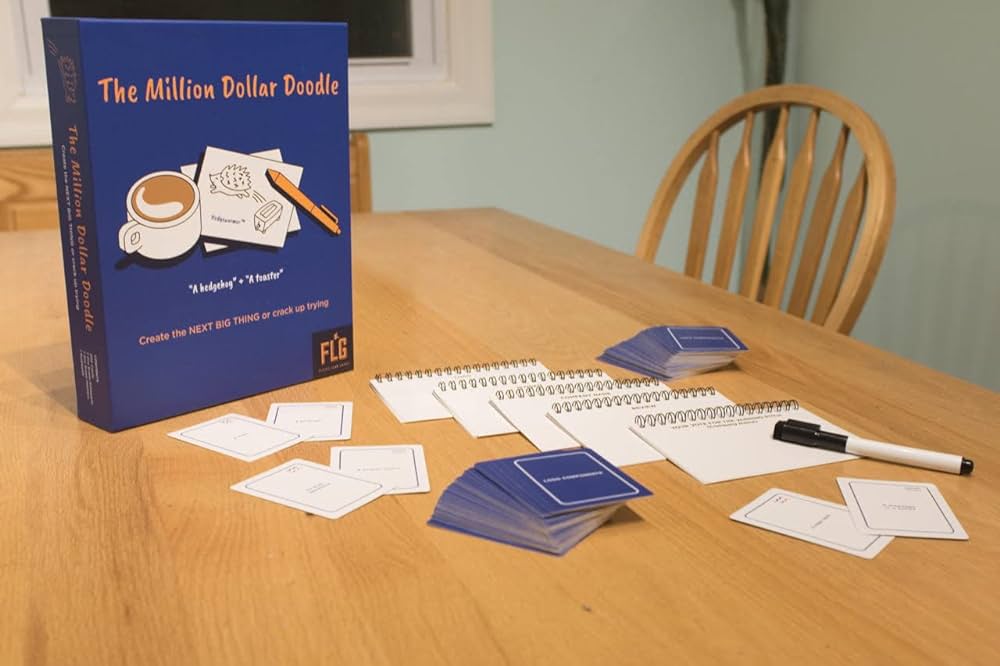

The difference in physical implementation between the two games translates to quite different mechanics and dynamics. MDD relies primarily on whiteboard booklets whereas Posh Pooch uses a deck of cards. This simple distinction means the two games sit on either side of various design tradeoffs. For one, MDD gives players more room for creativity than Posh Pooch, since MDD players can draw or write anything that fits their prompt. However, this means MDD is more mentally demanding of players than Posh Pooch, which only requires collecting and trading pre-designed cards. Posh Pooch therefore has more room for additional mechanics that add more dimensions to the game, mechanics like trading and bluffing. But Posh Pooch also needs these additional mechanics to exist for the game to be fun for players, as reducing the challenge of a game risks boredom. Iterating on our design will require us to return to these design trade-offs repeatedly and reassess whether we are navigating them appropriately.

Design Conflict

Despite the difference in mechanics and dynamics, the two games strive to create similar aesthetics. In MDD, players are trying to give cohesive pitches. However, the initial company concept comes from two randomly drawn cards, which adds unpredictability. Furthermore, each element of the company concept comes from a different player, so the final concept can be quite disjointed. Plus, because players who are contributing to the company concept aren’t the ones pitching it they tend to take bigger swings. This makes it challenging to come up with a cohesive pitch, and the humor of the game comes from the absurdity of the resulting pitches. In Posh Pooch, accessories may or may not tell a cohesive story because the accessories players receive are up to chance and what other players are willing to trade. The pitches therefore require jumping through some hoops to justify, creating a similar aesthetic to MDD. On the other hand, Posh Pooch also includes design conflicts coming from bluffing and from playing cards on other players’ pooches. Both games try to create similar aesthetics of fellowship, but Posh Pooch tries to go the extra mile and integrate aesthetics of competition. As we iterate on our design, we’ll be reevaluating how these aesthetics work together and how we can create a cohesive experience that leans into both aesthetics.