Monopoly Deal is an analog card game designed for players aged 8+, catering to families and casual gamers alike, and was released by Hasbro, Inc. I played two rounds of the game in my dorm with my roommate and some other friends. I’m very familiar with the game as I grew up playing it in my family and am a big fan! In this critical play, I argue that the formal game elements of Monopoly Deal enhance the emergence of fellowship as a central game aesthetic, promoting interdependency among players via a requirement that players react and adapt to the actions of others continuously. In contrast, the current prototype of our team’s game “Wild Wild West” currently lacks mechanisms that allow for player creativity and collaboration, focusing instead on straightforward, competitive gameplay. There are important lessons to be learned from Monopoly Deal in creating the competitive ambiguity that is necessary to activate fellowship as a central mechanic.

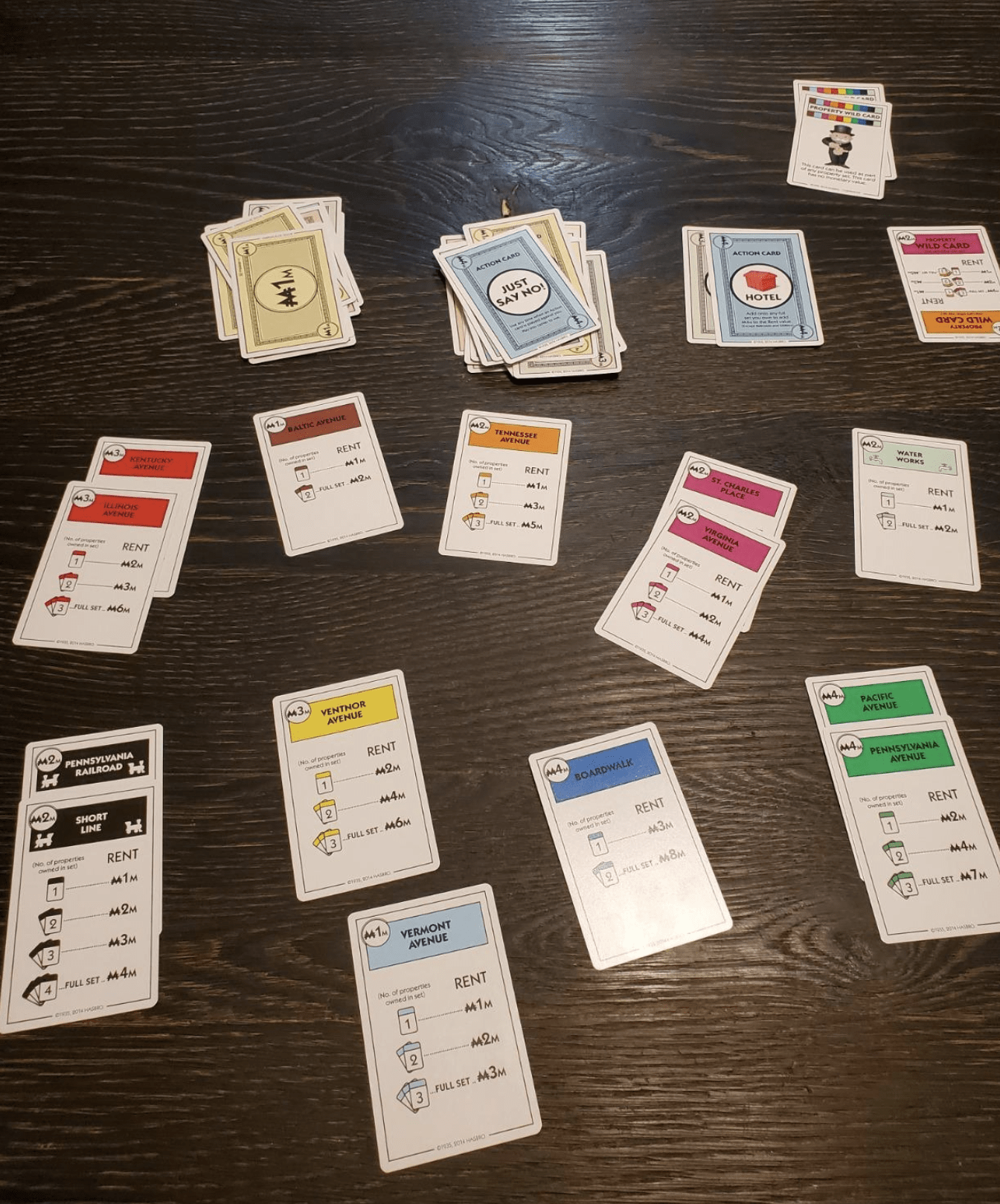

In both Monopoly Deal and Wild Wild West, the game’s structure demands a high level of engagement with other players’ actions. For example, a player might state as one of my friend’s did in our game that, “I’d like to have rent for this blue property – you owe me seven million,” which is an obvious example of the game’s dependency on others’ assets and decisions. Our own game, Wild Wild West is similar to Monopoly Deal in this regard, as players have cards that require taking assets from other players as well. But this highlighted for me some important difference that make decision making feel more “fun” and actually engage the fellowship aesthetic; as it stands, the taking of assets is more of a rote decision as there is a clearly optimal choice, and the player only has one possible response. Rather in Monopoly deal, you can pay people rent through either money if you have it, or with property, which adds extra choice and strategy. The Wild Wild West cards directly affect coin totals either by stealing from others or safeguarding one’s own coins. This design focuses on individual taking and requires no interactive choice of your competitor, lacking the layered player engagement seen in Monopoly Deal.

Applying the Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics (MDA) framework gives us some interesting insights. Monopoly Deal’s dynamics involve negotiation, bluffing, (in our game we even added trading even thought I’m not sure that’s a thing), and strategic timing. In such a dynamic, fellowship interactions are crucial to gameplay success. On the other hand, Wild Wild West could benefit from integrating mechanics that encourage more complex player interactions and strategies, perhaps by adding cards that can be played in response to others’ actions, thus introducing a layer of collaborative or competitive strategy beyond direct confrontation. One place where Wild Wild West succeeds and is similar to Monopoly Deal is that we give the player a choice on how many cards to play; likewise, the rules of Monopoly Deal dictate that players can anywhere from 0 to 3 cards per turn, creating a strategic depth where players must decide not only which cards to play but also predict or react to the plays of others. However, the trouble for our game is there aren’t strategic reasons NOT to play cards at the moment, so that’s certainly an area to improve.

When thinking about concrete improvements to Wild Wild West I found Wodtke’s article very compelling. For example, I love Wodtke’s idea that “not all companies address a problem; some look for opportunities” which for me means that Wild Wild West may benefit from identifying and integrating successful strategic elements from other genres to enhance its gameplay. But recalling when Wodtke notes, “Be careful not to over-borrow: keep your design choices contextual to your product space” reminds us that thematic coherence of elements from Monopoly Deal is paramount. One fun mechanic I noticed in Monopoly Deal is the core aspect of card management as a test case. One quote from our game was “ok I guess I have to discard now because I can only have 7 cards or less.” This boundary on the game represents an opportunity to have new emergent experiences arise that add important context to our product space. I think if we pay attention to these lessons of continuous, dynamic interaction from Monopoly Deal and apply them to our own team project we will be very successful indeed.