The Chameleon is a unilateral competition and social deduction game created by Big Potato Games. The game targets 3-8 players with ages 14+ and has both online and card versions. I played its online version with my friends. Our team wants to make a recipe-building game, What’s For Dinner, where one player, the judge, selects a dish and lets all other players, the chefs, know, and then the chefs each pick an ingredient from the given list and describe it in one word sequentially, while there is a spy chef hidden and trying to let the judge guess the dish wrongly. The spy chef will win if the judge guesses the dish incorrectly and also guesses the wrong spy chef; otherwise, the judge and the normal chefs will win. Our team targets on 5-6 players with ages 5+.

Central Argument

This game is similar to our game as they are both quick social deduction games focusing on unilateral competition to find out the “spy” within all players while the two games differ in their premise, procedure, resources, and some rules, which generate different challenges. Overall, the two games are similar in their win+lose outcomes, and the game shape focuses on fellowship, competition, and challenges as the goal is for the good team to find the spy while the spy needs to try his/her best to hide in the unilateral competition setting, while the rules enhance such challenges. However, the premises of the games are totally different given the settings of the two games: simply guessing the spy given the words versus a slightly longer procedure from guessing the dish to guessing the spy under a story of finding out what to eat for dinner. Such differences would bring players different types of challenges and fun.

Analysis

The general challenges of the two games are similar. The spy needs to hide from being detected, and the good team needs to find the spy. The rules add extra challenges to this process in that each player can only say one word. However, the players of the two games face different challenges and dynamics to achieve this goal due to different procedures and rules. In The Chameleon game, the good team needs to try letting each other know their identities but also want to control how much to disclose so that the spy can not easily guess the word. In our game, the challenges for the good team originate from how to describe the ingredients they pick clearly enough for other good chefs to understand so that they will not pick the same ingredient, and for the judge to be less impacted by the wrong ingredient picked by the spy. The spy cares less about whether his/her identity would be detected by other good chefs as only the judge needs to detect the spy so that he/she aims at picking an ingredient that is confusing enough for the judge to guess the dish and the spy wrongly. In this way, the spy in our game enjoys major fun from sabotaging the dish while the spy in The Chameleon receives fun from disguising his/her identity.

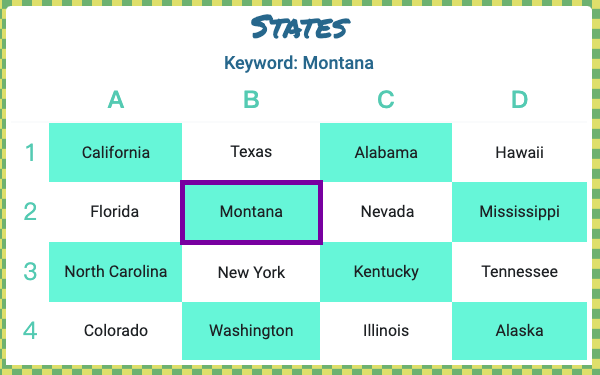

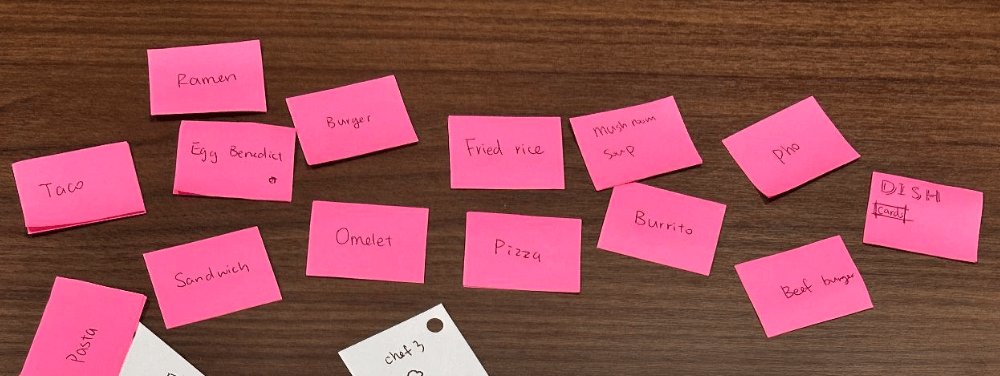

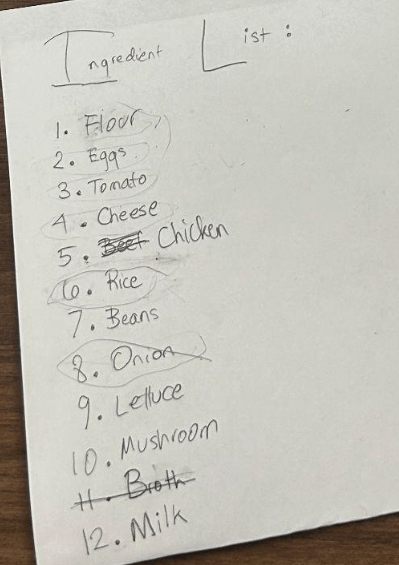

Looking closer at the resources, besides character cards, both of the games have lists of target words (dish in our game) as resources, and we also have another ingredient list that players could pick from. The chameleon game has various lists of words while some of the words require vocabulary background or understanding of the concepts around them. For example, I received the word for the state Montana but barely had an opinion of where the state is and how to describe it as I am not a U.S. citizen, so I needed to quickly search in Google to continue playing this game. I believe this might also be one of the reasons why this game targets players aged 14+. We faced similar issues when designing the dish and ingredient cards where we found some words or dishes might be too hard to make so that there would be barriers for players to have fun. Given this, in our concept, we hope to make the dish and ingredients easy enough so that all players with ages 5+ can enjoy the game. Our games also add additional dynamics by introducing the ingredients list. With this list, the players could have some guidance on how the dishes could be created while also enjoying the fun of getting the wrong ingredients within the boundary list.

Finally, both games might have similar limitations mostly originating from the order of the description of the word or ingredients. For example, if the spy unluckily needs to speak first, he/she is really unlikely to win given no clues on what the actual word is and losing the fun of guessing other’s word and disguising his/her identity. In our game, we find similar issues when the spy needs to pick and describe the ingredient first as this might limit his/her chances to win as the spy needs to pick the wrong ingredient to confuse the judge and if the spy does this before other chefs, other chefs can easily recognize this and try their best correcting the dish’s ingredients. We aim to reduce such impact as we enable the spy to also know the correct dist so that the spy can have a clearer idea on what dish to confuse the judge with. However, such limitation might still appear given that the spy needs to give the first description not knowing anyone else’s choices. Maybe this could be avoided if there is an extra moderator in the game who knows everything and decides the correct order, but this also has the limitation that the players will know that the first player speaking is not the spy, and the moderator will lose the fun from not being included in the game. In general, we still hope to find out during prototyping whether the order will make our game lose this balance on how hard it is for the spy to win, and maybe it could bring extra dynamics instead of being a limitation.