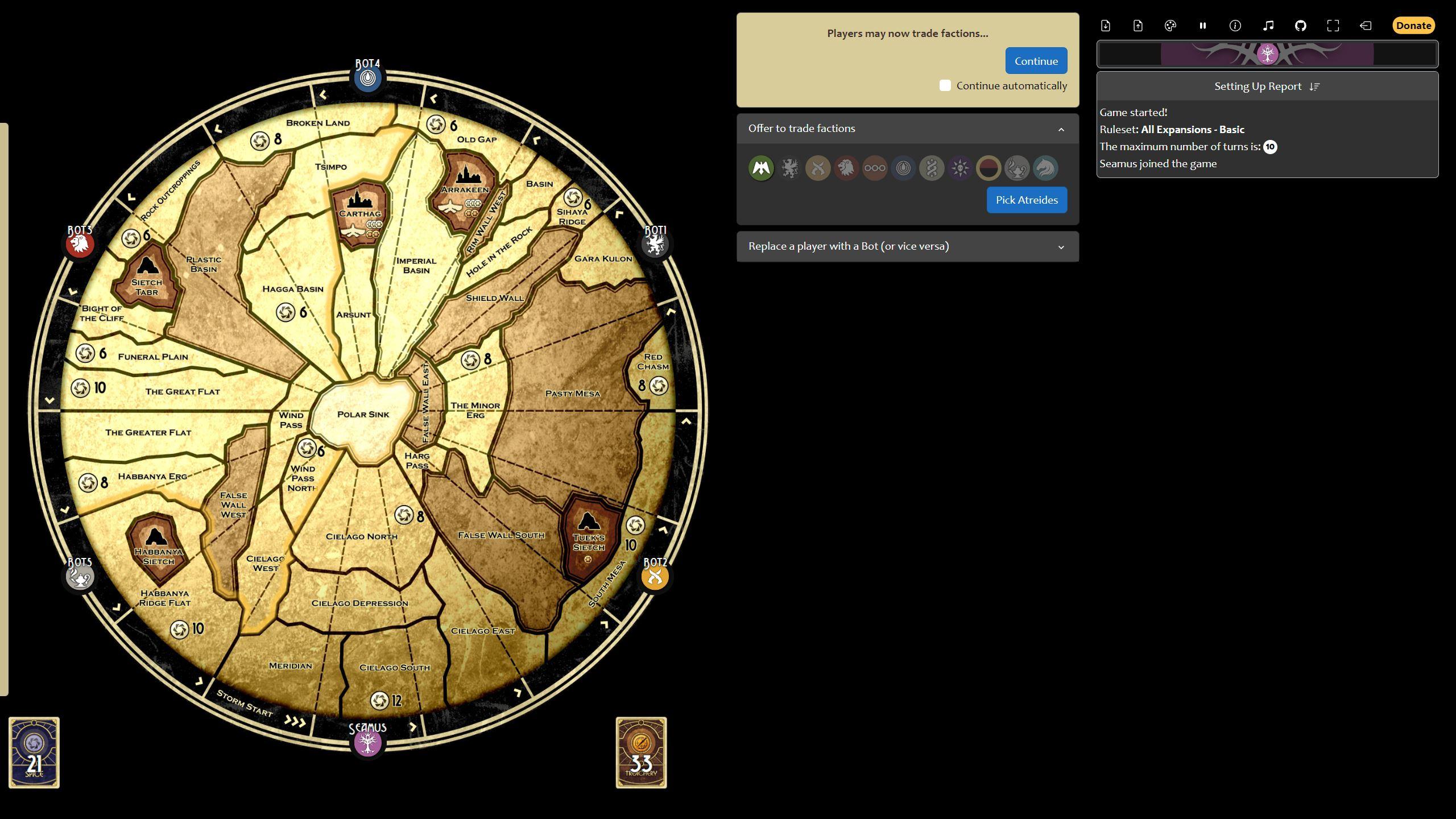

I selected Dune for my critical play because it is highly asymmetrical and involves a lot of trading, something our game also plans to be.

In Dune, some players have a lot and others have very little, but each still has something the other needs. The Emperor, for example, is usually incredibly flush with spice (the game’s main resource), because they get all the spice bid in card auctions by other players. However, they struggle to translate this wealth into victory in combat the same way the Harkonen can and lack the wealth of foresight the Atreides possess.

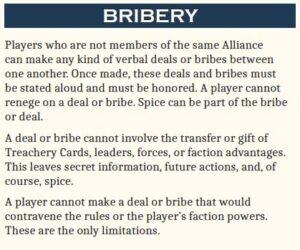

Dune’s dynamic of frequent trading is further facilitated by Spice, a highly fungible resource that everyone needs for almost everything they do and therefore can be easily exchanged.

This kind of fungible resource is something our game currently lacks—our resource cards can only be used to either solve a crisis or be stashed away for points at the end of the game. Not having a spice-like resource in our prototype prevents the sort of tiny side deals and power-sharing arrangements that Dune thrives on.

My group has discussed the creation of a 0-point wildcard resource that could serve this function, but we haven’t landed on anything that would work without adding substantial additional complexity. Dune is an area control game, and ours is not. Our simpler ruleset focused narrowly on negotiation ultimately affords less nuance.

There is another set of mechanics in Dune that creates a dynamic of rampant bribery and negotiation, however, which I do think we could emulate. In Dune, everyone has a monopoly on something that they can sell to the other players. For example, only the Atreides can tell you what the current treachery card on auction is. In my game, the Atreides wound up setting a “going rate” to tell you what the card in question was—but modified it on a couple of occasions to mess with people. Because each faction has something unique to offer, no one was completely passed over in negotiations. To achieve a similar effect, we plan to take advantage of our existing crisis cards and place unique effects on them that take place when they are resolved. This will give each player something unique to work with in negotiations. Unlike Dune, these would not be stable resources assigned based on your role/faction—you get new crisis cards every round. We tested this approach on Sunday with a few prototype cards, and it went great. We’re currently working on brainstorming more of them.

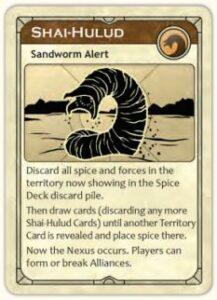

The other unique element from Dune relevant here is the extent to which it allows its formal elements to be modified during play. At certain points during the game, players have the opportunity to ally, attempting to achieve a more difficult objective in coordination with another player rather than a less difficult objective alone. In my game, two alliances of two players formed, transforming the game from multilateral to team competition, which felt like an amazing change of pace. This also changed the outcome of the game—you won or lost as a team, with another player.

Though we embrace the asymmetry of Dune’s factions in our Emperor/Advisor dynamic, I doubt this dramatic rearrangement of formal elements would make sense for our game, which is intended to be much shorter than Dune. That said, as multiple different players take on the role of emperor throughout a game, who the target of our unilateral competition is will change, providing what I hope is equally refreshing variety in the game’s structure.

Finally, our early tests suggest a substantially different game feel from Dune. Dune was created in 1979, and today, the mechanics feel notably old-school. The best way I can describe it is to say that the specificity of certain rules, the ability for the game to end incredibly early, and the possibility of sudden dramatic changes in standing give the game a rough, gritty texture. It is an experience unlike the smooth, neatly organized one you might get from a modern title like Scythe, but not an overall unpleasant one. I believe our game will ultimately adopt a more modern feel, sporting fairly minimalist systems and a fixed-length experience that aims to keep everyone at least in the running until close to the end. I hope this makes our game more accessible to a broad audience—though this will potentially come at the cost of the endless depth a game like Dune offers to board game veterans.