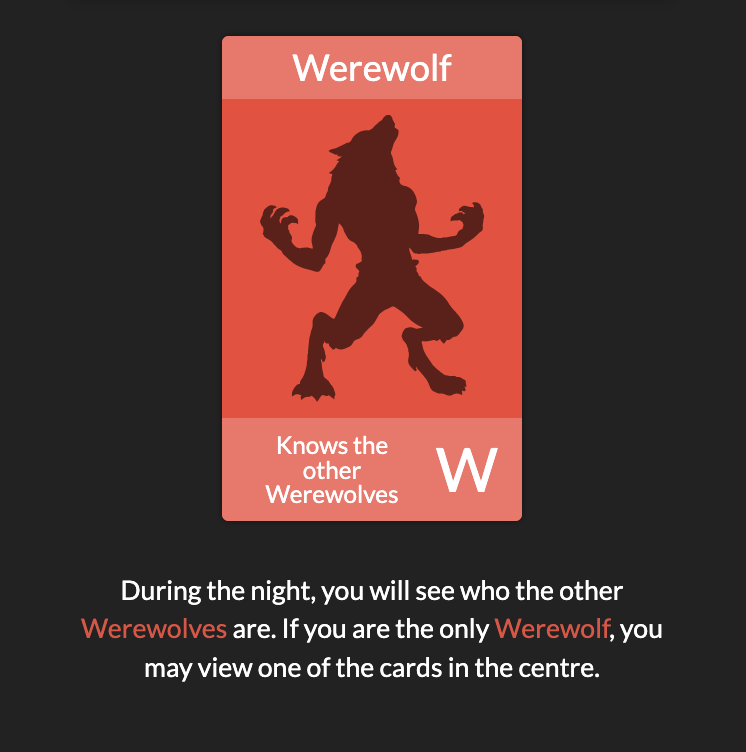

One-Night Ultimate Werewolf, designed by Bezier games, is a social deduction game designed for audiences of players eight years and up (however the intricacies of the game and deception often involved leads me to suggest that players be 10 or 12 and up so they possess the cognitive and social reasoning appropriate to enjoy the game). I opted for the online version of this game. This game is set within the confines of a single “night” (basically a single round of gameplay) where players are randomly assigned different roles either on the Werewolf or Villager teams. In Mafia-style, everyone closes their eyes. Depending on each player’s role, they will open their eyes at a designated time, perform certain actions (such as looking at a player’s card, swapping cards, or identifying other players) and close them again. After this series of secret actions, the group has to come together and accuse, argue, and explain in a group discussion in order to determine who they each think is a Werewolf. Each player votes, and if a true Werewolf receives the most votes, the Villagers win, and if anyone on the Villager team receives the most votes, then the Werewolves win, giving the game a Team vs. Team setup. With its simple premise, One-Night Ultimate Werewolf thrives in its very dynamic player-driven narrative with numerous possible roles and its single-night setup that heightens tension and encourages risk-taking.

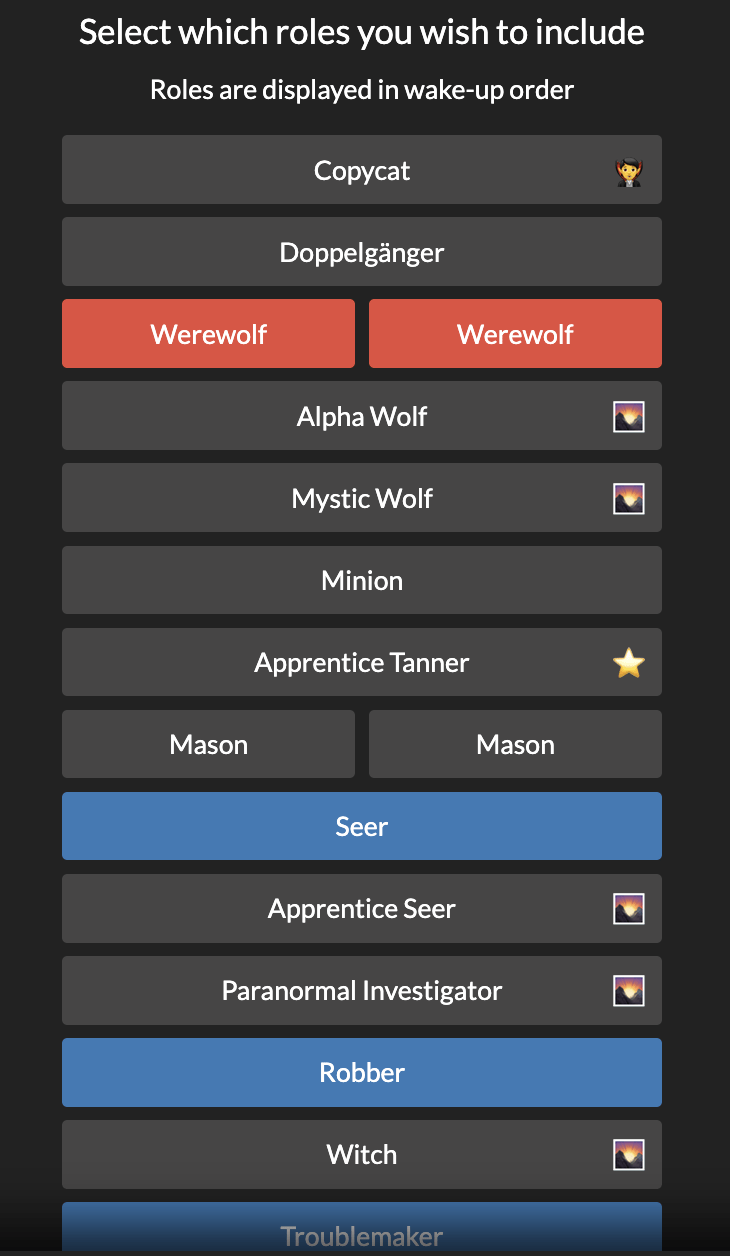

One innovation in One-Night Ultimate Werewolf’s approach to social deduction gaming comes from intricacies of the player’s secret roles and their relationships to one another. The online version offers 28 different roles to use in the game, with some roles belonging to the Werewolf team and others to the Villager team.

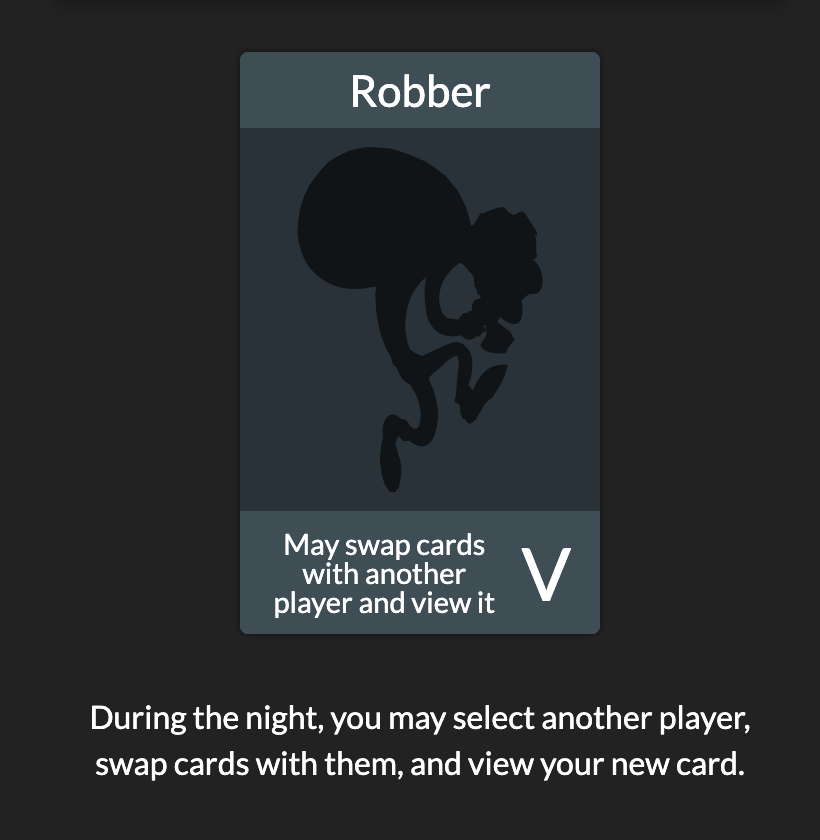

Unlike other social deception games such as Secret Hitler (where my friends and I sometimes find the Liberal roles relatively non-exciting) almost every role in One-Night Ultimate Werewolf is heavily involved in the round’s events. This is because most of the Villager roles also involve interaction with other players. For example, the Robber, on the Villager team, will swap roles with another player and then view their new card. However, another player with a different role, such as the Seer, may see this player’s card before or after the swap sometime during the round as well. The number of different roles, their interdependence, and the impact of the order of events in the round all contribute to a very intricate dynamic between players that is exciting whatever role you take on.

Additionally, the single “night” (round) setup of One-Night Ultimate Werewolf heightens the excitement of the game and incentivizes risk taking. Unlike longer social deception games with multiple rounds (such as Secret Hitler), being caught for lying does not affect future rounds, since the game only lasts for one. As a result when we were Werewolves, we felt that we were more likely to lie and deceive than in our past experiences playing Secret Hitler when we were Fascists. Or, if we were Villagers, we were more likely to make dramatic accusations without fear of “looking guilty” or being wrong, since our roles wouldn’t persist for a second round. Given this single night setup, we also enjoyed getting to play many games back-to-back since each game didn’t last too long. Although each outcome was technically zero-sum, I found myself more interested in the proportions of wins that I would get. Additionally, the most important outcome from each game was gaining knowledge about other players’ typical strategies to help in future games, rather than the result of any one individual game.

Another observation I had was that the boundaries of the game expanded beyond the group of four of us that were playing. Although the “official” boundary of the game exists only for a few minutes in each game between the four players of the game, we found that this expanded to a roommate who happened to be around while we were playing. Although he didn’t officially join the game as a Werewolf or Villager, he found himself watching and enjoying our arguments, explanations, and conversations, especially since he knew who was lying and telling the truth. Additionally, the social interactions from One-Night Ultimate Werewolf led to insights about one another that carried throughout the rest of the night and weekend.

Although I really enjoyed One-Night Ultimate Werewolf, there were a couple of areas I think could be improved or expanded upon. One such area is to add some sort of wagering system when someone votes differently than the rest of the players. There were several times where one of us would feel particularly proud for successfully identifying the Werewolf while other Villagers failed to do so or agree. In these cases, we would lose despite our correct detective work. It would be cool to be able to wager on a Werewolf in these cases. This change would have to be incorporated into larger changes within the outcome of the game, as it wouldn’t coincide with the official zero-sum outcome, but it could maybe fit into a multi-round version of the game where each player racks up points throughout the outcome of individual rounds.