Coup–designed by Rikki Tahta and published by both “Indie Boards and Cards” and “La Mame Games”–is a 2012 social deduction card game. It is rated for ages 14+, but the target audience is a small group keen on deceiving each other and figuring out when they are being deceived. The mechanics are slightly too complicated for a pick-up-and-play with strangers at a party game, but it’s a great party game if everyone playing is intimately familiar with the mechanics.

The core fun of this game revolves around its tightly structured system of lying, deception, and card counting. There are five characters, there are three copies of each character in the deck, and each player is given two (potentially two identical characters) at the start of the game. The fact that each player is given exactly two cards leads to very interesting dynamics because these cards also act as a player’s health. Losing a single card is a serious handicap as it limits your legal moves, limits your ability to lie, and puts you one move away from being eliminated. On the flip side, this same mechanic also creates a consistent intensity curve that ramps up as the game progresses and an inverse deception curve that decreases as the game progresses. In the early game, it is extraordinarily advantageous to lie since there is not enough available information to reliably determine if someone is lying, and failing a challenge against someone leads to the aforementioned serious handicap. As such, the first few rounds of the game are quite boring and boil down to simple card counting. This is the part of the game that would benefit the most from improvements. The game relies heavily on tracking information throughout the game, and it often feels like the game does not truly start until players can begin determining the cards the other players are holding.

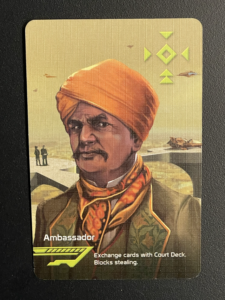

On the topic of information tracking, I want to point out an interesting design choice that impacts the whole game, but it is most prevalent in the early game: deck shuffling and the Ambassador. In Coup, the deck is only drawn from with the Ambassador character’s ability, and it is only reshuffled and drawn from upon a successful defense of a challenge. As mentioned previously, challenges increase in frequency as the game progresses, so card drawings in the early game are effectively exclusive to the Ambassador. The Ambassador’s mechanics are interesting in that they do not shuffle the deck. Instead, players can only interact with the top two cards on the deck. This makes the Ambassador an extraordinarily powerful early game character as they provide the first person who uses it with critical information on the game’s trajectory. Additionally, it is not very difficult to play “optimally” most of the time, so the first person to use the Ambassador card can be pretty confident in which cards (if any) the next players to use the Ambassador card will choose to keep. This makes it much harder to bluff against this player, and I believe it provides too big of an advantage. Finally, the first person to use the Ambassador card will presumably keep the best options, so this makes all future Ambassador uses objectively worse. I believe it would be better if the Ambassador returned one card to the top of the deck and one card to the bottom of the deck. This would diminish the power of the Ambassador and prevent the first person who uses it from having an information advantage for (effectively) the rest of the game.

Finally, I want to point out a critical weakness with the Assassin Character’s ability and how it impacts the end game. If someone has only one influence left and is targeted by an Assassin, it is always optimal for them to claim a Contessa Counteraction and attempt to block the assassination. If they fail the challenge, they are eliminated. If they do not challenge, they are eliminated. This makes the Assassin card a one-time-use if a player is targeting someone with only one influence, and it makes it impossible to bluff with the Assassin in the end game. This leads to the end game always being a slow drag to seven coins. Lying and deceiving becomes extremely difficult, and the game is usually decided several turns before the game actually concludes.

Although Coup’s formal elements fall apart in the early game and end game, the mid game masters the tight system discussed in the second paragraph. It emphasizes the Discovery and Challenge types of fun more broadly, and it does a great job of always keeping everyone on edge. During the mid game, it is near impossible to feel safe, and it makes the deception feel extremely risky, necessary, and fun all at the same time.